The Minoprio Collection: British Design in the Arts & Crafts Tradition | 669

Live Online | Edinburgh

PAST AUCTION

LOT 1

ANTHONY MINOPRIO (1900–1988) (DESIGNER), PETER WAALS (1870-1937) (MAKER)

COCKTAIL CABINET, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £6,250

LOT 2

ANTHONY MINOPRIO (1900–1988) (DESIGNER), PETER WAALS (1870-1937) (MAKER)

WARDROBE, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £7,500

LOT 3

ANTHONY MINOPRIO (1900–1988) (DESIGNER), PETER WAALS (1870-1937) (MAKER)

BED, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £813

LOT 4

ANTHONY MINOPRIO (1900–1988) (DESIGNER), PETER WAALS (1870-1937) (MAKER)

DRESSING CHEST & MIRROR, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £3,000

LOT 5

ANTHONY MINOPRIO (1900–1988) (DESIGNER), PETER WAALS (1870-1937) (MAKER), JOHN SKEAPING R.A. (1901-1980) (CARVER)

CELLARETTE, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £3,000

LOT 6

ANTHONY MINOPRIO (1900–1988) (DESIGNER), PETER WAALS (1870-1937) (MAKER)

WRITING DESK, CIRCA 1930

SOLD FOR £9,375

LOT 7

PETER WAALS (1870-1937)

STATIONERY BOX, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £1,500

LOT 8

ANTHONY MINOPRIO (1900–1988) (DESIGNER), PETER WAALS (1870-1937) (MAKER)

THREE-TIER OCCASIONAL TABLE, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £3,250

LOT 9

PETER WAALS (1870-1937)

OCCASIONAL TABLE, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £2,125

LOT 10

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

STANDING SHOE CUPBOARD, CIRCA 1952

SOLD FOR £30,000

LOT 11

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

TWIN-PEDESTAL DESK, CIRCA 1973

SOLD FOR £13,750

LOT 12

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

SMALL ARMCHAIR, CIRCA 1964

SOLD FOR £813

LOT 13

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

BUREAU, CIRCA 1964

SOLD FOR £2,500

LOT 14

PETER WAALS (1870-1937)

TWO-TIER TABLE, CIRCA 1930

SOLD FOR £12,500

LOT 15

HUGH BIRKETT (1919-2002)

TABLE LAMP, CIRCA 1950

SOLD FOR £8,750

LOT 16

OLIVER MOREL (1916-2003)

BLANKET CHEST, DATED 1969

SOLD FOR £4,750

LOT 17

STANLEY WEBB DAVIES (1894–1978)

OCCASIONAL TABLE, DATED 1929

SOLD FOR £5,500

LOT 18

COTSWOLD SCHOOL

CABINET, CIRCA 1930

SOLD FOR £1,750

LOT 19

COTSWOLD SCHOOL

TWO-TIER OCCASIONAL TABLE, CIRCA 1930

SOLD FOR £938

LOT 20

W.A.S. BENSON (1854-1924)

PAIR OF THREE-LIGHT CANDLESTICKS, CIRCA 1900

SOLD FOR £3,750

LOT 22

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

SECRETAIRE DESK, CIRCA 1933

SOLD FOR £22,500

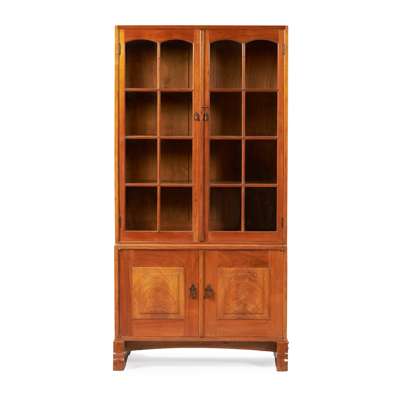

LOT 23

PETER WAALS (1870-1937)

CABINET BOOKCASE, CIRCA 1929

SOLD FOR £12,500

LOT 24

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

DRESSER, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £22,500

LOT 25

PETER WAALS (1870-1937)

WARDROBE, CIRCA 1935

SOLD FOR £2,250

LOT 26

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

DRINKS/ RECORD CABINET, CIRCA 1965

SOLD FOR £3,500

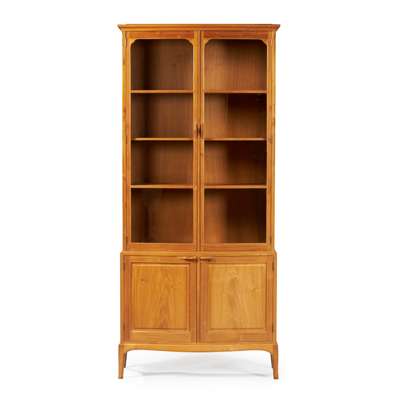

LOT 27

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

BOW-FRONT DISPLAY CABINET, CIRCA 1972

SOLD FOR £3,250

LOT 28

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

PAIR OF DISPLAY CABINETS, CIRCA 1966

SOLD FOR £13,750

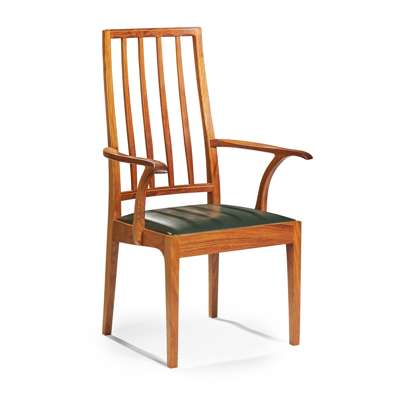

LOT 29

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

PAIR OF TALL ARMCHAIRS, CIRCA 1980

SOLD FOR £5,000

LOT 30

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

HANGING CONSOLE TABLE, CIRCA 1981

SOLD FOR £2,750

LOT 31

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

ROUND DINING TABLE, CIRCA 1978

SOLD FOR £3,500

LOT 32

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

PAIR OF BOW-FRONT WARDROBES, CIRCA 1980

SOLD FOR £3,000

LOT 33

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

DOUBLE BED, CIRCA 1962

SOLD FOR £1,375

LOT 34

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

BOW-FRONT CHEST OF DRAWERS, DATED 1966

SOLD FOR £5,000

LOT 35

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

BOW-FRONT WARDROBE, CIRCA 1950

SOLD FOR £2,750

LOT 36

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

TALL ARMCHAIR, CIRCA 1981

SOLD FOR £1,125

LOT 37

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

STANDING SHOE CUPBOARD, CIRCA 1966

SOLD FOR £5,750

LOT 38

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

SERPENTINE CHEST OF DRAWERS, CIRCA 1982

SOLD FOR £5,250

LOT 39

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

ROUND TABLE, CIRCA 1972

SOLD FOR £2,000

LOT 40

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

SET OF TEN DINING CHAIRS, CIRCA 1981

SOLD FOR £10,625

LOT 41

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

DINING TABLE, CIRCA 1980

SOLD FOR £2,693

LOT 42

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

WRITING CABINET, CIRCA 1972

SOLD FOR £22,500

LOT 43

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

CHAIR, CIRCA 1950

SOLD FOR £475

LOT 44

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

DRESSING TABLE, CIRCA 1950

SOLD FOR £3,500

LOT 45

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

BOOKCASE CHEST, CIRCA 1950

SOLD FOR £2,500

LOT 46

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

TALL CHEST OF DRAWERS, CIRCA 1950

SOLD FOR £5,250

LOT 47

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

PAIR OF SINGLE BEDS, CIRCA 1950

SOLD FOR £1,250

LOT 48

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

TALL ARMCHAIR, CIRCA 1975

SOLD FOR £1,188

LOT 49

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

DINING TABLE, CIRCA 1980

SOLD FOR £1,500

LOT 50

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

SET OF SIX DINING CHAIRS, CIRCA 1970

SOLD FOR £4,000

LOT 51

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

ROUND DINING TABLE, CIRCA 1977

SOLD FOR £4,750

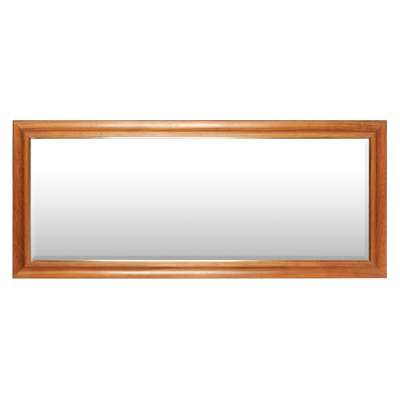

LOT 52

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

WALL MIRROR, CIRCA 1978

SOLD FOR £1,063

LOT 53

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

BOW-FRONT WARDROBE, CIRCA 1956

SOLD FOR £9,375

LOT 54

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

PAIR OF HANGING CORNER CUPBOARDS, CIRCA 1978

SOLD FOR £2,375

LOT 55

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

TOY CUPBOARD, CIRCA 1970

SOLD FOR £2,250

LOT 56

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

ARMCHAIR, CIRCA 1981

SOLD FOR £1,375

LOT 57

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

DRESSING CHEST, CIRCA 1950

SOLD FOR £2,125

LOT 58

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

DESK, CIRCA 1981

SOLD FOR £18,750

LOT 59

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

PAIR OF STATIONERY TRAYS, CIRCA 1982

SOLD FOR £750

LOT 60

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987) AND JON BARNSLEY (1930-2004)

WASTE PAPER BOX, CIRCA 1983

SOLD FOR £1,500

LOT 61

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

FILING CABINET, CIRCA 1981

SOLD FOR £5,250

LOT 62

EDWARD BARNSLEY (1900-1987)

LOW COFFEE TABLE, CIRCA 1981

SOLD FOR £2,125

LOT 63

W. J. TANNER

BOOK TROUGH, CIRCA 1970

SOLD FOR £500

LOT 64

JON BARNSLEY (1930-2004) FOR THE EDWARD BARNSLEY WORKSHOP

ADJUSTABLE MUSIC STAND, CIRCA 1987

SOLD FOR £2,750

LOT 65

JAMES RYAN FOR THE EDWARD BARNSLEY WORKSHOP

STOOL/ TABLE, CIRCA 2005

SOLD FOR £1,375

LOT 66

JAMES RYAN FOR THE EDWARD BARNSLEY WORKSHOP

WRITING TABLE, DATED 2015

SOLD FOR £6,875