It was at the beginning of the 18th century that precious gem set jewellery started to come to the fore, and while in previous decades the wearing of jewellery was often a religious or political statement, it was then that jewellery began to become more closely aligned with the necessity to follow fashionable society.

Jewels Through the Ages: The Georgian Period

9 July 2014

Ruth Davis

The Indian mines from which most of Europe had sourced their diamonds were beginning to dry up at the start of the 18th century, however the discovery of large deposits in Brazil during the 1720s meant that a new and abundant source now flooded the market, making diamonds that bit more affordable. It was also during this period, that the distinction between what was appropriate jewellery for the daytime, as opposed to what was appropriate for the evening, began to emerge. Coloured stones and gold work, pieces like chatelaines, were considered best for day wear, while diamonds and pearls – shown to their most glittering advantage under the candle lit chandeliers of ballrooms, were reserved almost exclusively for the evening.

Fashionable Design

At the turn of the 18th century, design began to move away from opulent closely clustered designs, to much more natural, symmetrical flowing floral or ribbon and bow designs. As the Rococo style became more popular during the 1730s, asymmetrical formal designs also emerged, however examples of these are less common. Large diamond set perures were designed for the wealthy women of the European courts, allowing their every inch to be festooned in diamonds. Girandole earrings hung below hair ornaments, often modelled as a bunch of flowers or ears of wheat; necklaces were worn high on the neck, often pearls (a great display of wealth and status) or diamond riviere necklaces. Stomachers, large brooches fitted to the front of a bodice, often had to be fitted in sections to allow the wearer to move, while smaller brooches and buttons would be pinned throughout, often functioning as clasp to hold the garment together.

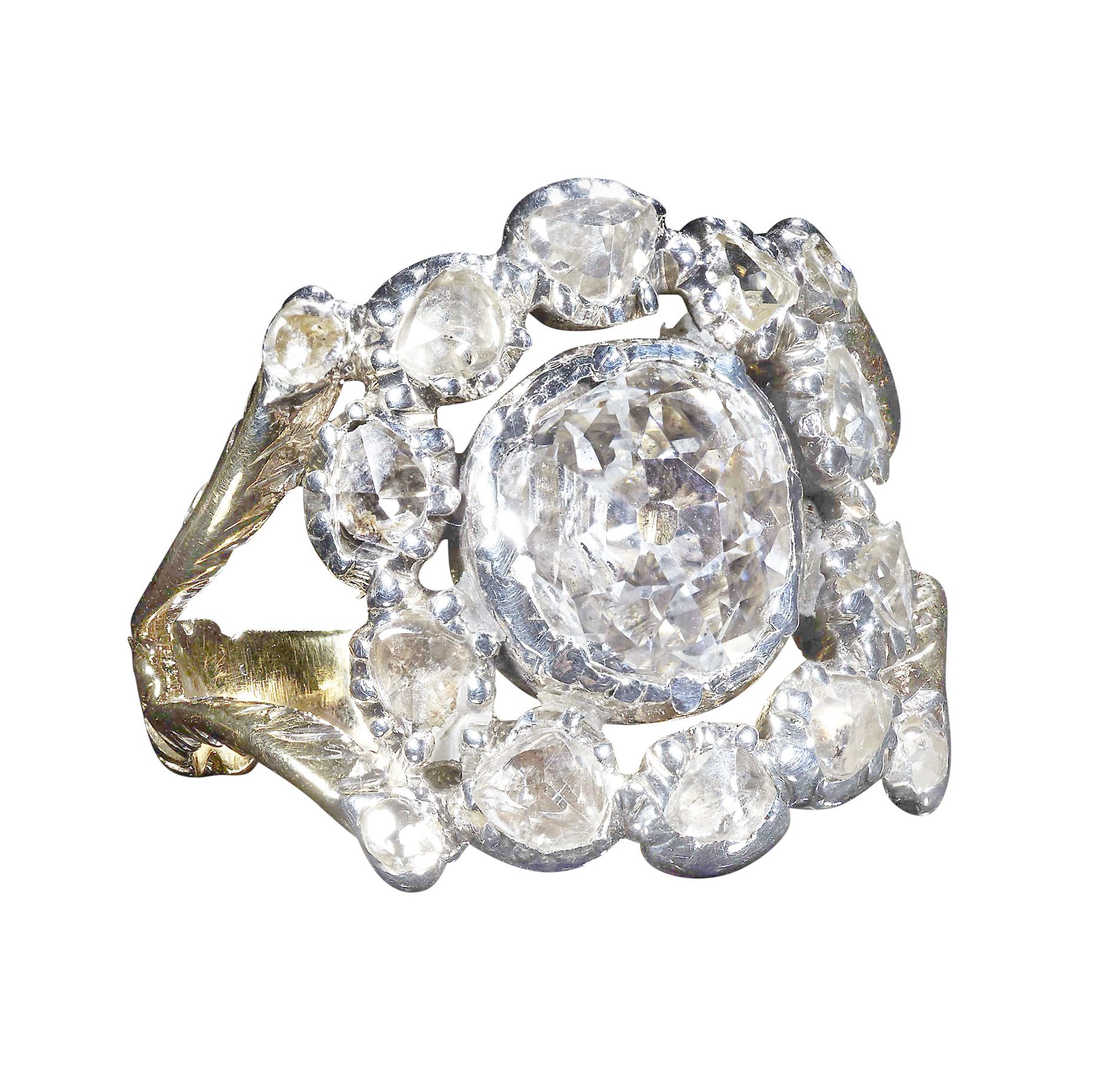

Paste Jewellery

Today paste jewellery is a very important academic resource for jewellery historians, as there aren’t an awful lot of original precious metal and diamond set examples of Georgian pieces left; often successive generations of wealthy families remodelled their family jewels in line with the most current fashions. During the French Revolution, jewellery became closely associated with monarchy and the old regime, and so in a time when a diamond shoe buckle was evidence enough to send the wearer to the guillotine, families either sold their jewels when they fled the country, or else they were ‘donated’ to the revolutionary cause. Again, it was during the 18th century that paste jewellery came to the fore, they were more affordable alternatives but also desirable pieces in their own right, various jewellers specialising in paste held royal warrants. During the first half of the century French Jeweller Georges-Frederic Strass developed a more durable type of paste, a mix of flint glass and lead oxide, which was hard enough to be facetted; allowing a better quality of paste jewellery to become prolific.

Mourning Jewellery

Mourning jewellery is another important aspect of the Georgian period, and subtle messages in their design allowed the knowledgable observer to decipher hidden messages. For example, black enamel is commonly seen in surviving examples today and denoted those who were married from the white enamel used for those who weren’t. It was not uncommon for the deceased to have left provisions in their will for family members to commission these pieces. The name, age and the date of death are often inscribed, and from the middle of the century motifs such as urns, broken pillars or weeping willows also feature. Seed pearls and hair were also commonly worked into the composition; indeed, we still see complete watch chains or bracelets made entirely from intricately woven strands of hair which survive to this day.

Lovers Tokens

Rings and lockets, with painted ivory scenes or portraits in a surround of gemstones or diamonds were commonly given as tokens of love, and are another rich source of secret messages. Locks of hair were often hidden behind the central panels, visible only from the back, so only the wearer knew they were there. Padlock or key motifs represented a heart given in love, while a serpent biting its tail represented eternity. These amatory jewels were worn by men and women; men often concealing them beneath a shirt or on a watch fob, while women commonly wore them as pendants and rings. Particularly charming examples developed in France during the 1780s in which the portrait miniature shows only the painted eye of the wearers beloved, a far more teasing and secretive way of keeping the sitters identity a mystery.

The Neo-Classical

During and immediately after the French Revolution, gold was in extremely short supply in France, and this gave rise to much more delicate designs, increasing inspired by antiquity; motifs such a laurel leaves and geometric Greek key designs. Napoleon was increasingly concerned with aligning his regime to those great empires of the past, and this gave rise to the use of cameos and hardstone intaglios, such as carnelian in jewellery, particularly those which were archaeological finds or depicted imagery of antiquity. Fashion had begun to relinquish the stiff bodice and more flowing materials took their place, allowing for a more controlled but still elaborate aesthetic typically composed of a large coloured gemstone, in a border of diamonds. Micromosaic panels, though costly and time consuming to make, were also popular, and remained so until the late 1800s, often depicting Roman ruins, flowers and birds; they remain a popular collectors piece to this day.

It is difficult to capture the essence of such a rich period of jewellery in such few words, however highlighting just a few of the fashionable aspects goes some way to demonstrating that while jewellery is in its purest form a means of adornment. it also reflects the shifts of political, sociological and artistic development which took place during this period which still influence us today.

Jewellery

Lyon & Turnbull's team of jewellery specialists’ - including gemmologists Ruth Davis and Charlotte Peel - extensive knowledge and experience of the current market provides the essential combination for the successful sales of both modern and antique jewellery; from fine Edwardian and Victorian pearls, through classic diamonds, sapphires, rubies and emeralds from the houses of Cartier, Boucheron, Bulgari and Tiffany, all the way to the outrageously decadent designs of Grima and the understated, elegant works of Jensen.