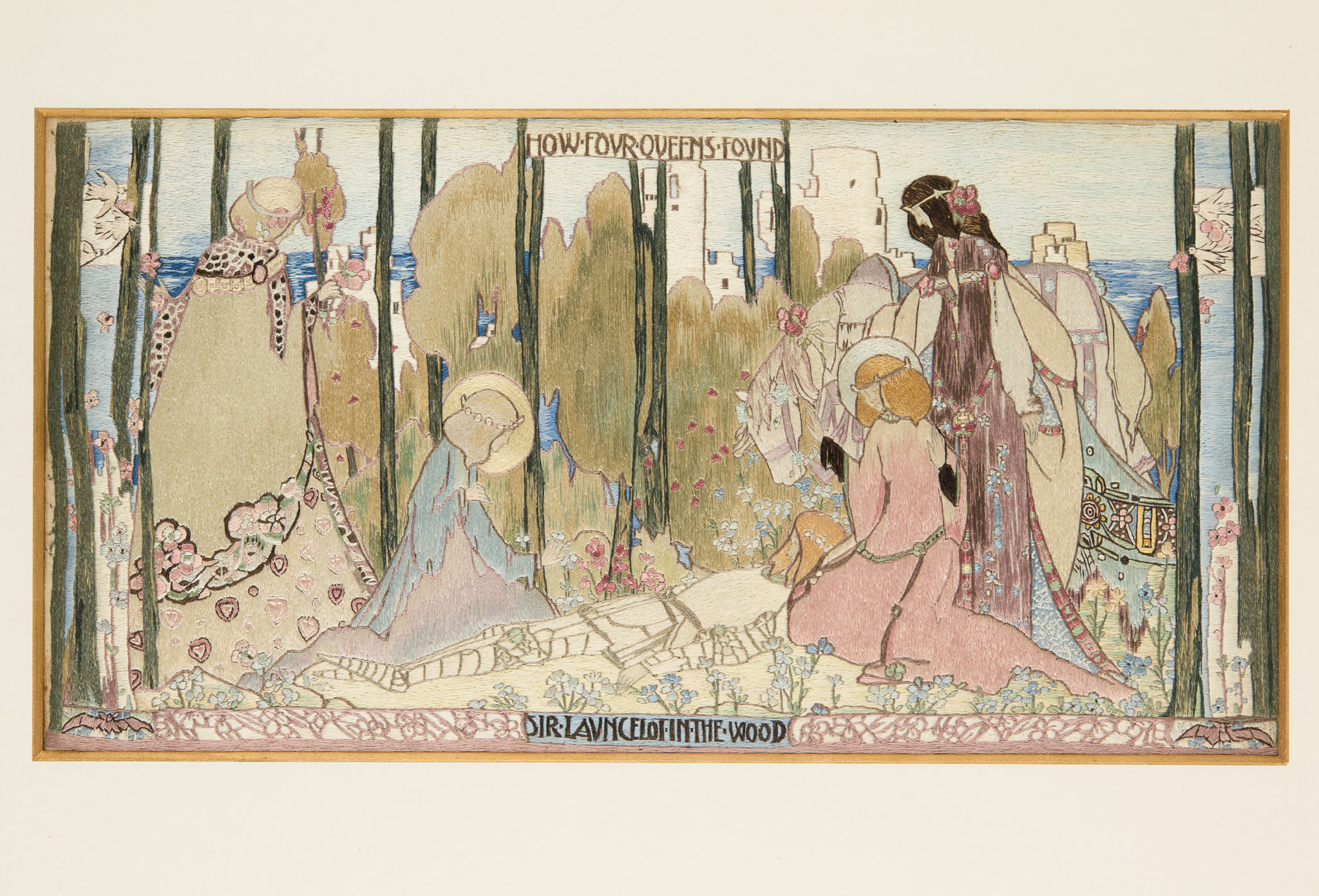

Lot 278

JESSIE MARION KING (1875-1949) AND ELISE PRIOLEAU

‘HOW FOUR QUEENS FOUND SIR LANCELOT IN THE WOOD’, CIRCA 1910

Auction: Day Two | Lots 253 to 490 | Thursday 17th April from 10am

Description

coloured silks, framed

Dimensions

20.5cm x 41cm (frame size 48cm x 65.5cm)

Provenance

Provenance: Jessie Marion King and Ernest Archibald Taylor

By descent to their daughter Merle Taylor

Estate of Merle Taylor

Footnote

Literature: The Studio, no. 213, December 1910, pp. 232-235, illustrated in colour p.233

White C. The Enchanted World of Jessie M King, Canongate 1989, p.33, pl.28 illustrated

Exhibited: Barclay Lennie Fine Art Limited, Glasgow, Jessie Marion King Exhibition 2nd-25th November 1989, no. 45 Dumfries and Galloway Museum Service Tolbooth Art Centre, Kirkcudbright, Jessie M King Anniversary Exhibition, June 4th - July 18th 1899, no. 20

The Glasgow School of Art Jessie M King Anniversary Exhibition, 27 July-3 September 1999, no. 54

Jessie M King’s ‘How Four Queens Found Sir Lancelot in the Wood’ employs striking design and skilful execution to illustrate a beguiling legend. Most intriguing of all however, is the artistic partnership behind its creation, a piece of the puzzle so often extinguished from the history of decorative art.

The embroidery was executed around the time King and her husband E. A. Taylor were living in France. The couple moved to Paris in 1910 and founded the Shearing Atelier School of art. It can be argued that some of her finest works belong to this Paris period, including pieces considered influential to the creation of the Art Deco movement.

This work marked the genesis of a collaboration between King and Paris based embroiderer Madame Elise Prioleau. Despite her French sounding name, Prioleau was descended from an ancient English family and married to a banker from South Carolina. Prior to King’s move to France, Prioleau had contacted the artist via letter. A feeling was present amongst artistic circles that contemporary embroidery lacked imaginative input and was instead producing ‘insipid and meaningless’ works, a fault of the designers rather than the embroiderers. This was a sentiment with which Prioleau agreed, hence why, on seeing King’s inspired illustrations in the Studio magazine, she suggested collaboration.

The subject of the embroidery is taken from the 15th century prose work Le Morte d’Arthur by Thomas Mallory, an interpretation of the legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Chapter three, Book VI, Volume I describes how four fantastical queens discover Sir Lancelot resting beneath an apple tree. Having placed an enchantment, they take him to a castle where he must choose between picking a queen as his ‘paramour’ or death.

Prioleau was sent a small watercolour of the design, and having traced it onto canvas, she then painstakingly worked the piece in silk threads. She was a master of her art, praised by Colin White for her use of satin stitch ‘cleverly angled across the picture like brushstrokes’, the effect being a ‘three-dimensional appearance’. Despite White’s comparison of threads with paint, E.A. Taylor in a Studio magazine article of December 1910 considers ‘How Four Queens Found Sir Lancelot in the Wood’ to be refreshingly original precisely because to him, Prioleau seems ‘at pains to avoid imitating…the pictorial painter’. The association between King and Prioleau was not limited to this piece, the duo producing works including ‘Richard Coeur de Lion’, also illustrated in the Studio. This was a fruitful and widely admired artistic partnership.

‘How Four Queens Found Sir Lancelot’ enjoyed exposure in the foremost artistic forums of the day. A full-page colour image was first reproduced in the December 1910 volume of the Studio magazine with an accompanying article discussing the state of embroidery in Paris, as well as the design featuring in ‘The Studio Year Book of Decorative Art’ the same year. Then, in 1912 the work was displayed at the Musée Galleria exhibition of embroidery, a show reported upon in the September edition of the Studio magazine. In both instances, the partnership between King and Prioleau is described in glowing terms. Whilst E. A. Taylor, King’s husband, is the author of both articles and therefore not an unbiased reporter, the publicity the embroidery received and consequently the high regard with which it must have been viewed is undeniable.