Lot 34

Arabic manuscripts - Egypt & Arabia

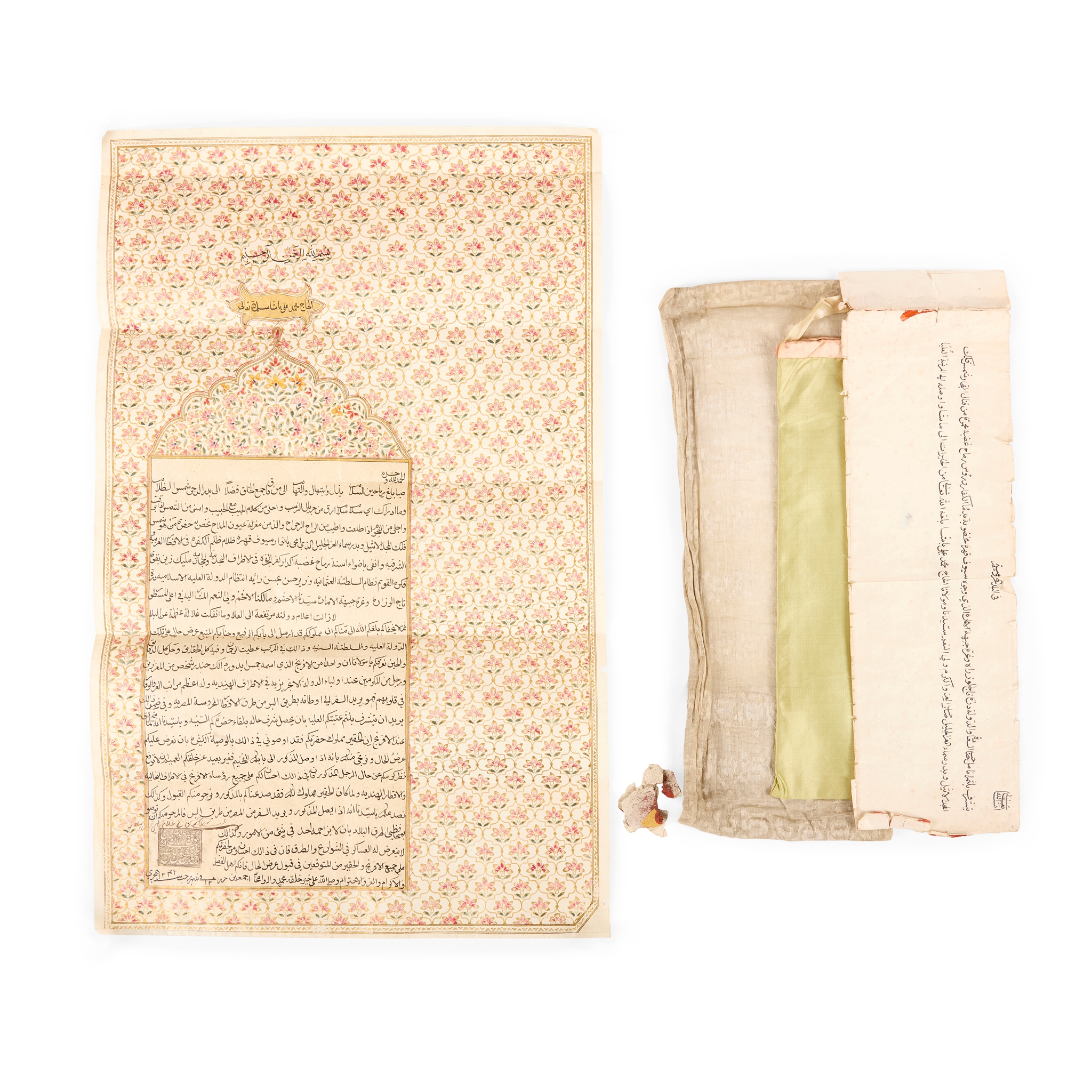

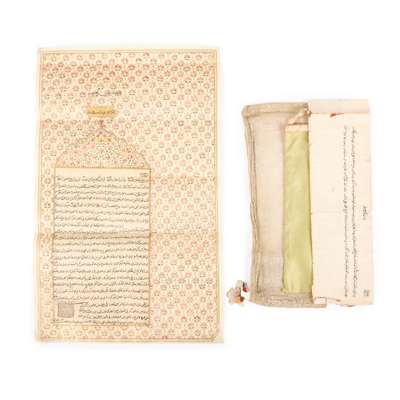

Four illuminated petitions addressed to Ottoman commanders including Muhammad Ali Pasha

Auction: The Library of General Sir James Alexander | Wed 25 February from 10am | Lots 31 to 62

Description

requesting permission for James Edward Alexander (1803-1885) to travel overland through Egypt.

12 & 18 Rajab 1241 AH [19th & 25th February 1826].

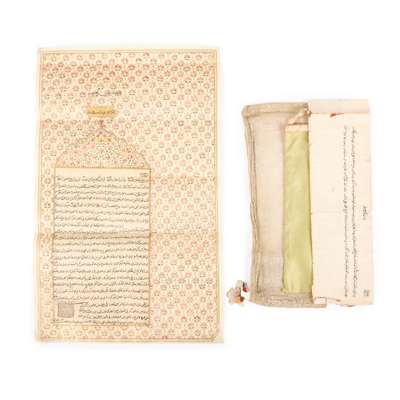

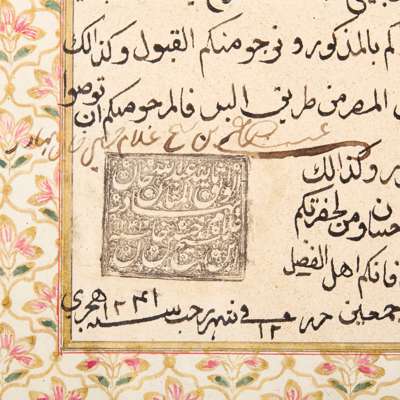

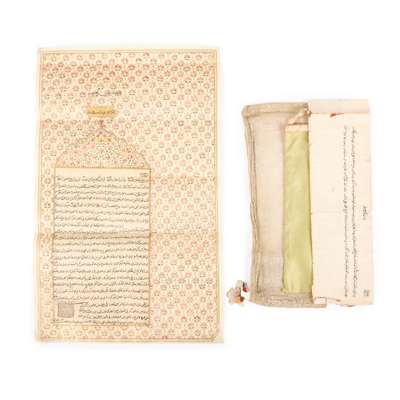

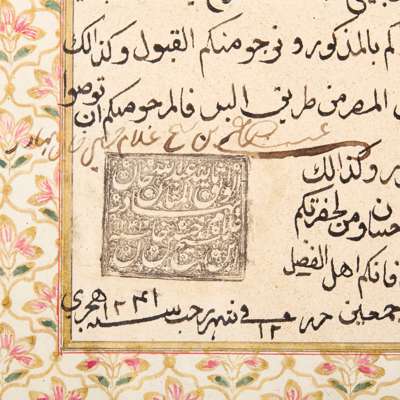

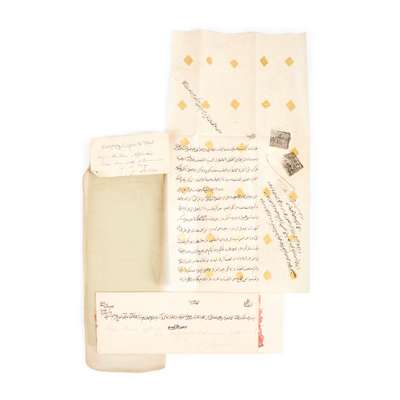

4 Arabic manuscripts, each in black ink on one side only of a single sheet of polished wove paper, naskh script, folding into envelope annotated in Arabic with salutation to the recipient and with the name and office of the recipient in English, housed in a separate green silk drawstring document bag (except the letter to Hasan Aga) and cream gauze outer sleeve, with signature and ink-stamp of one Abdullah Khan bin Shaykh Ghulam Husayn Khan Bahadur at foot, presumably a munshi in the service of the East India Company, and his red wax seal to envelopes, the letters respectively addressed to:

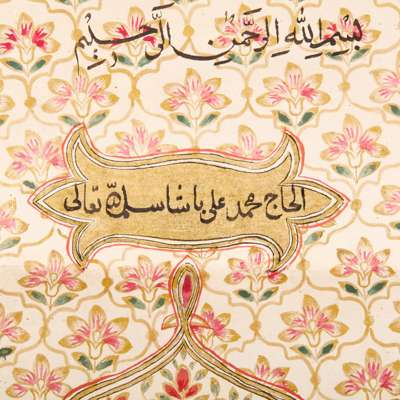

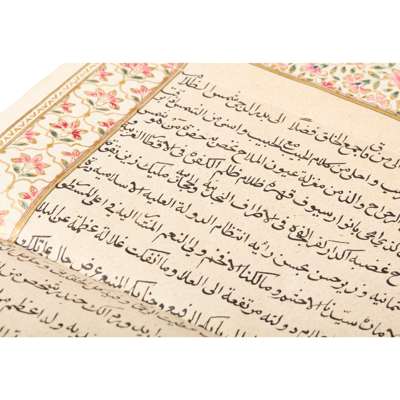

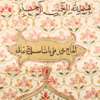

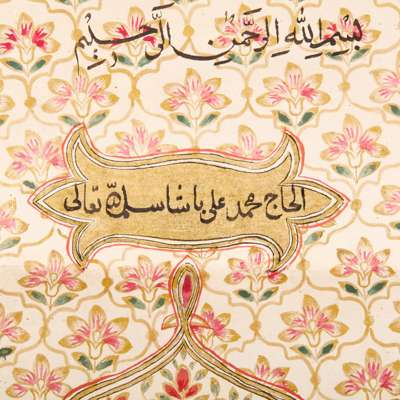

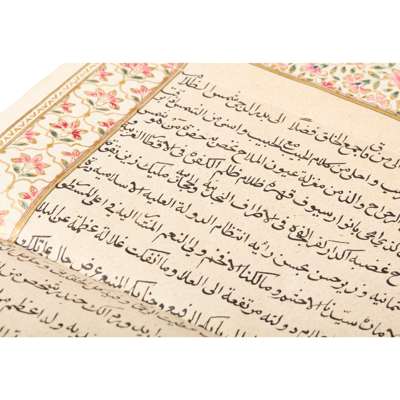

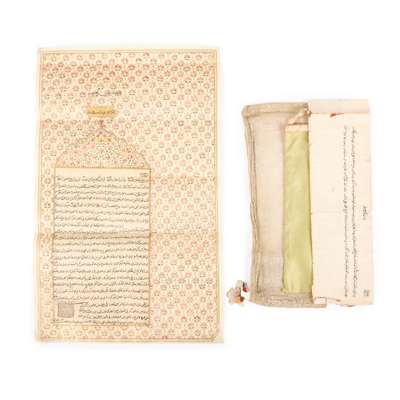

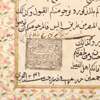

Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha (1769-1849), governor of Egypt. 12 Rajab 1241 [19th February 1826], 61 x 38cm, cusped panel to head containing salutation al-Hajji Muhammad ‘Ali Basha sallamahu al-ta’ala written on gold ground, the main text comprising 23 lines and set within large panel surmounted by a Moorish-style multifoil-arched top, elaborate decorative background composed of repeating polychromatic floral motifs within lattice of shaped quatrefoils in gold;

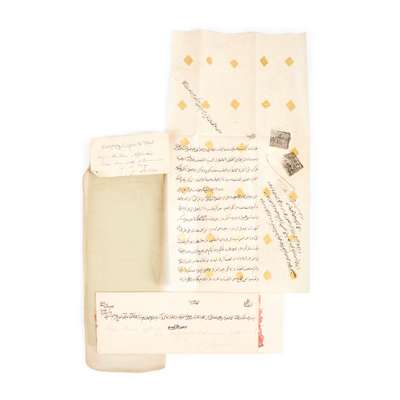

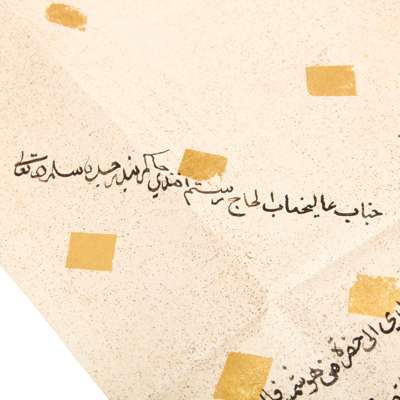

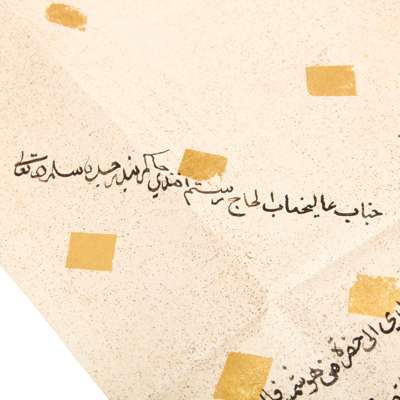

Mir Mahmud Bey Kakhiyah, minister of Muhammad ‘Ali Pasha at Suez. 12 Rajab 1241 [19th February 1826], 62.5 x 24cm, on gold-sprinkled paper decorated with rows of diamond lozenges in gold leaf, one-line initial salutation at head (written diagonally), 31 lines of text (the final 4 lines, including date, written diagonally in right-hand margin), manuscript docket inscribed in Arabic and English pinned to document bag (the English identifying the addressee as ‘Meer Mahmood Bey Koffeeah Wauzier to His Highness the pacha of Egypt at Suiss’);

Rustum Efendi, commander of Jeddah. 12 Rajab 1241 [25th February 1826], 43 x 23.5cm, on gold-sprinkled paper decorated with rows of diamond lozenges in gold leaf, one line salutation at head (written diagonally), Rustum Efendi identified as ‘hakim bandar Jiddah’ (commander of the port of Jeddah) in salutation at head of letter and on envelope, inscription in English to envelope and additional label (attached via red wax seal and cord to green silk document bag) reading ‘Haji Rustum Affundee, Judge, Magistrate & Commander of the Forces at Judda’;

Ra’is Hasan Agha, agent for trade and shipping, Jeddah (modern Saudi Arabia).

18 Rajab 1241 [25th February 1826], 59 x 23cm, on gold-sprinkled paper decorated with rows of diamond lozenges in gold leaf, one line initial salutation at head (written diagonally), 18 lines of text, Hasan Agha variously identified as ‘wakil al-tijarah wa’l-safa’in’ (i.e. ‘agent for trade and boats’) at head of letter, and ‘wakil al-tijarah’ (agent for trade) and ‘Chief in the civil & Marine Department, Judda’ in the Arabic and English inscriptions on the envelope, envelope additionally annotated with intended destination of bandar Jiddah (the port of Jeddah) in Arabic (4)

Provenance

THE LIBRARY OF GENERAL SIR JAMES EDWARD ALEXANDER (1803-1885)

Footnote

A major collection of original diplomatic documents in Arabic, representing the attempt of a young British army officer to return from India to England through the Egyptian heartlands of renegade Ottoman governor Muhammad Ali Pasha and his territories on the Arabian side of the Red Sea, recently acquired during the Ottoman-Wahhabi War. The year 1826 was one of revolution in the Ottoman Empire. In a dramatic turn of events over two days in June, Sultan Mahmud II outmanoeuvred and liquidated the powerful janissary corps, who had become an intolerable burden on the functioning of the state and a barrier to the modernisation of the Ottoman army. The Ottomans were at that point managing to contain the Greek rebellion which had begun in 1821, thanks to the mobilisation in 1825 of Muhammad Ali Pasha’s new European-style conscript army. It was Muhammad Ali Pasha’s success that emboldened Mahmud II to move against the janissaries, but also convinced the European powers of the necessity of uniting against Ottoman and Egyptian forces.

James Edward Alexander had joined the army of the East India Company in 1820, and served in the First Anglo-Burma War. After the end of hostilities in 1825 he intended to return to England via Egypt, and had these documents drawn up in preparation, but was stymied by the infrequency of available ships, as he recalled in his first book:

‘It had been my original intention to proceed homeward through Egypt; but finding, on my arrival at Bombay, that no vessel would sail for the Red Sea probably for six months, I was obliged to abandon this project, and had now no alternative … but to travel overland through Persia and Russia. It was proposed to me to attach myself to the mission of Colonel Macdonald, who had just sailed for Persia (Travels from India to England, 1827, p. 73).

The four letters, written in Arabic and following the conventions of Islamic petitions, seek permission for Alexander to travel overland (bi-tariq al-barr) through Egypt and thence to England. Alexander is referred to in the third person by the scribe, who draws attention both to Alexander’s non-Muslim status as one of the Afranj (Franks, i.e. Europeans), but also to his high rank in India. The letters to Muhammad Ali Pasha and Mir Mahmud Bey Kakhiyah describe him as ‘one of the most honoured personages and esteemed men in the opinion of the governors of the English empire in India lands’ (shakhs min al-mu’azzazzin wa-rajul min al-mukarramin ‘ind awliya’ al-dawlah al-Injiriziyah fi’l-atraj al-Hindiyah), while those to the two commanders at Jedda mention that Alexander comes from the taraf (literally ‘side’, but possibly ‘staff’) of ‘Burr’ or ‘Barr’, ‘gentleman of Calcutta, a Company general’ (sahib Kalkuta, sar’askar Kumbani), which is possibly a reference to Lieutenant-General Edward Burr (1749-1828) of the Madras establishment.

Although all signed by the same clerk, the letters contain interesting variations. Those to Muhammad Ali Pasha and Mir Mahmud Bey Kakhiyah both seek a personal audience with the recipient, while Rustum Efendi and Ra’is Hasan Agha are informed that Alexander shall be ‘under your gaze, shadow and protection, and no one shall say that with him shall be any followers (or a flock), soldiers or Bedu’ (yakun nazarukum ‘alayhi fa-huwa tahta zillikum wa himayatikum … ahad la yaqul lahu shay min al-ri’aya wa-min al-‘asakir wa’l-badu). Most striking of all is the lengthy salutation to Muhammad Ali Pasha, which specifically celebrates his victory over the Wahhabis, praising his defeat of the unbelievers of Nejd and the Hejaz ‘by the light of the spear-tips of his wrath’ (bi-adwa’ asinnat rimah ghadbihi).

Had Alexander succeeded in travelling through Egypt rather than Persia, these letters would have presumably been handed to their recipients and their survival rendered unlikely. It is tempting to speculate on the future of Alexander’s career had he obtained an audience with Muhammad Ali Pasha, whose transformation of the Ottoman army in Egypt into a modern fighting force relied on a cadre of European advisors.