Lot 4

Newton, Sir Isaac

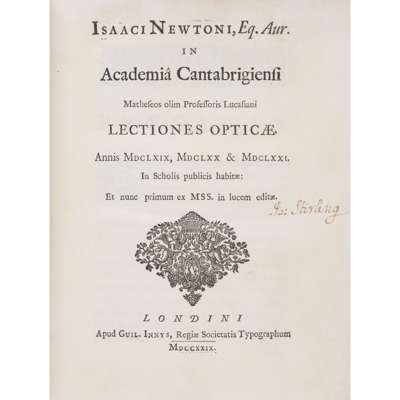

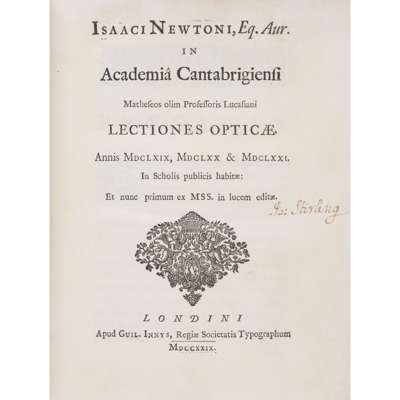

Lectiones opticae

The Library of James Stirling, Mathematician

Auction: 23 October 2025 from 13:00 BST

Description

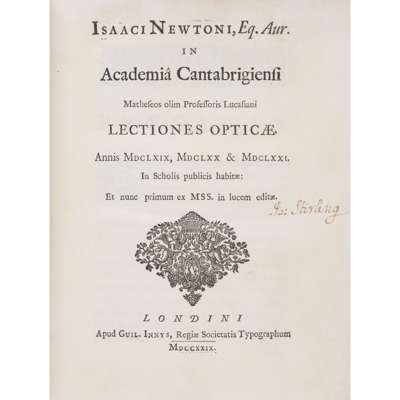

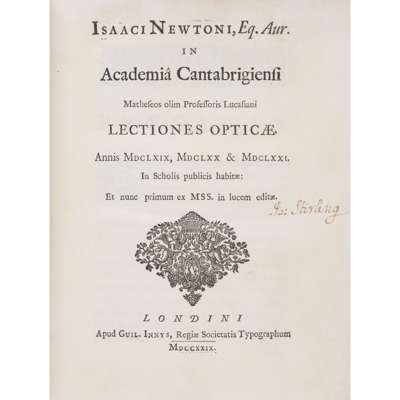

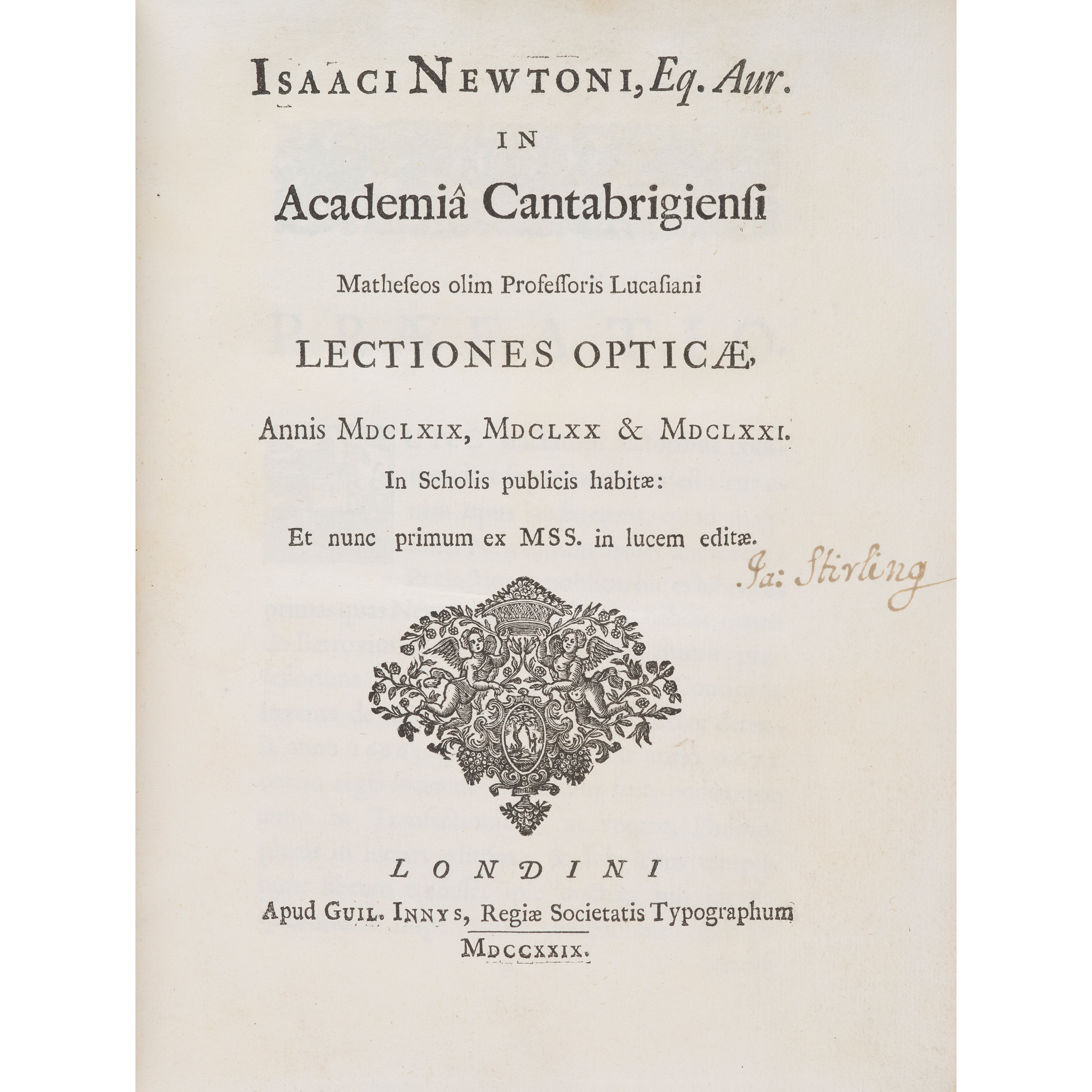

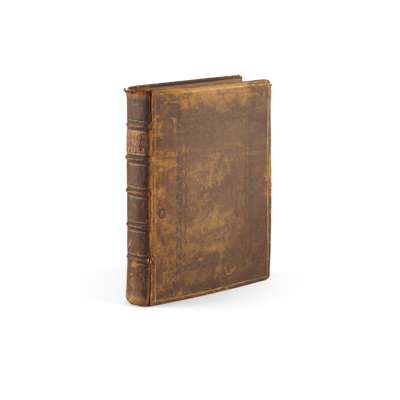

annis MDCLXIX, MDCLXX et MDCLXXI. In scholis publicis habitae: et nunc primum ex MSS. in lucem editae. London: apud Guil. Innys, 1729. 4to (22 x 16.2cm), contemporary calf, red morocco label, spine-compartments ruled in gilt, covers with gilt outer frames enclosing decorative roll-tool central panels in blind, xii 291 [5] pp., half-title, 21 engraved folding plates, binding rubbed, superficial cracking to joints, wear to head of spine [Babson 155; Wallis 191]

Footnote

Editio princeps (that is, the first edition in the original Latin) and the first complete edition, with James Stirling's ownership inscription ('Ja. Stirling') to the title-page, and his note of the book's presentation to him by one Edward Montague, esquire ('Ex dono Edvardi Montague armig.') in 1731 to the front pastedown.

Newton's inaugural lectures as the second Lucasian professor of mathematics at Cambridge were delivered between 1670 and 1672, and included details of his famous prism experiment. A partial English translation was published in 1728. ‘In 1669 Newton chose optics for his first lectures, and at that time he polished the theory of colours into its final form. The ’Lectiones opticae' ('Optical lectures'), deposited in the Cambridge University Library as the text of his first four sets of lectures, contains all the content of book one of the ultimate Opticks. About then he also returned to the experiment with Newton's rings, as they are still called, which would fill book two' (ODNB).

James Stirling was a follower of Newton from his time at Oxford, where he arrived in 1710. In 1715 John Keill noted in a letter to Newton that the problem of orthogonal trajectories proposed by Leibniz had recently been solved by ‘Mr. Stirling an under-graduate here’ (Tweedie, James Stirling: A Sketch of his Life and Works along with his Scientific Correspondence, 1922, p. 7). Stirling's first book, Lineae tertii ordinis Neutonianae, a commentary on Newton's classification of cubic curves, was printed at the Sheldonian Theatre in April 1717, with Newton listed as a subscriber. By that time Stirling's status as a non-juring student and his alleged involvement in Jacobite agitation had already led to trouble with the university authorities, however, and his scholarships appear to have been withdrawn shortly before the book was published. Leaving Oxford without a degree, he took up an invitation to Venice from Nicolas Tron, Venetian ambassador to London. In 1719, while still in Italy and apparently in dire straits, he received much-needed financial assistance from Newton, and once back in London called on him regularly during his final years, writing in a surviving letter from 1725: ‘Sr Isaac Newton lives a little way of in the country. I go frequently to see him, and find him extremely kind and serviceable in every thing I desire, but he is much failed and not able to do as he has done’ (Tweedie, p. 13). Stirling's principal work, the Methodus differentialis, a response to Newton's paper of the same name, appeared in 1730.