Lot 3

Newton, Sir Isaac

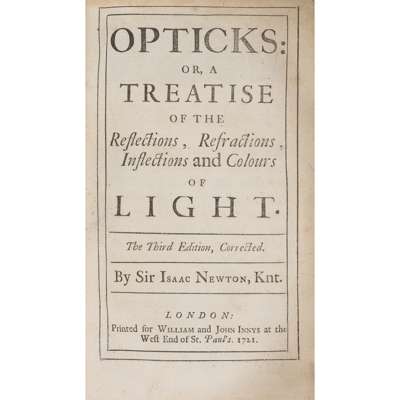

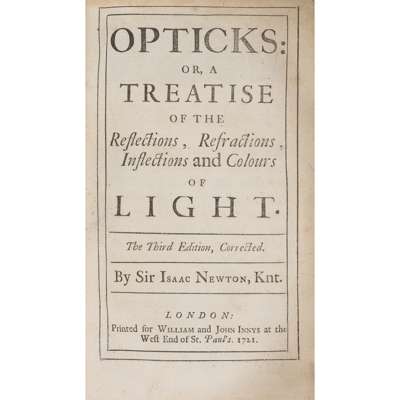

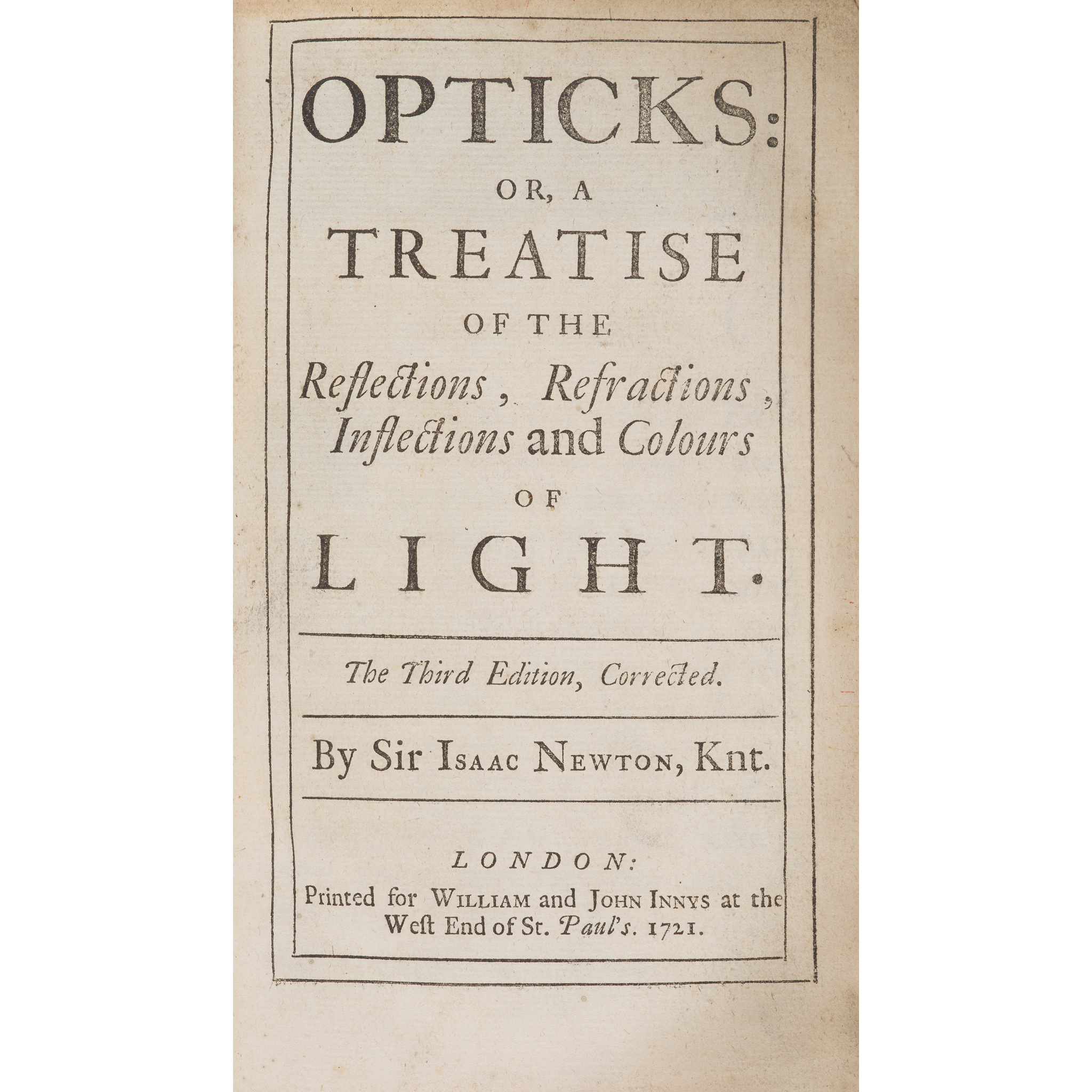

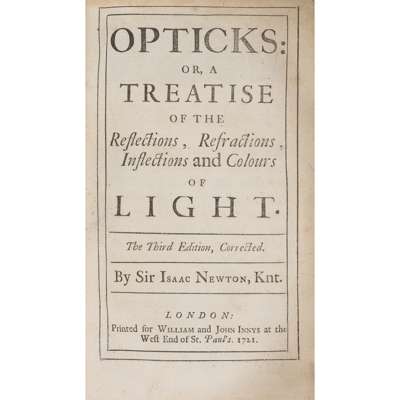

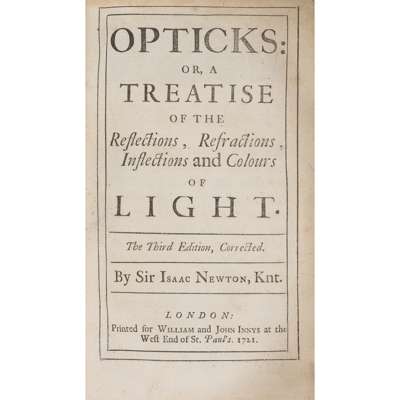

Opticks

The Library of James Stirling, Mathematician

Auction: 23 October 2025 from 13:00 BST

Description

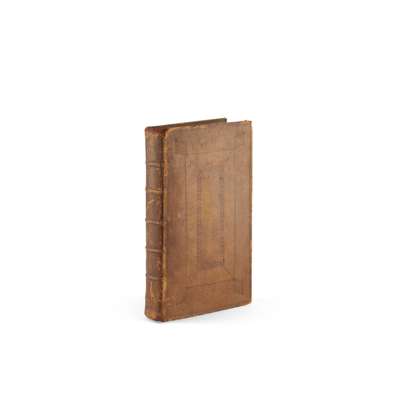

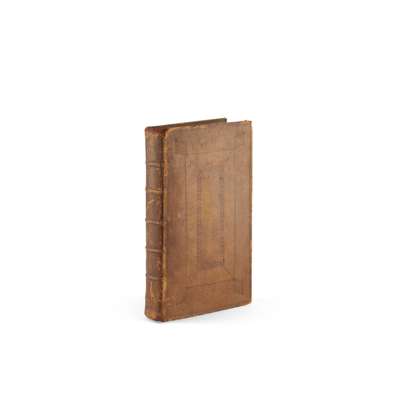

or, a Treatise of the Reflections, Refractions, Inflections and Colours of Light. London: for William and John Innys, 1721. 8vo (19.5 x 11.7cm), contemporary panelled calf, [8] 382 [2] pp., 12 engraved folding plates, woodcut head- and tailpieces and initials, advertisement leaf to rear, final plate with browning to fore margin [Babson 135; Wallis 177]

Footnote

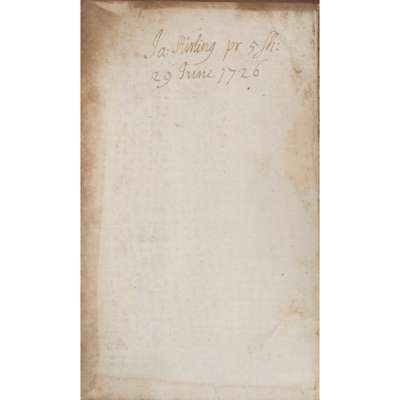

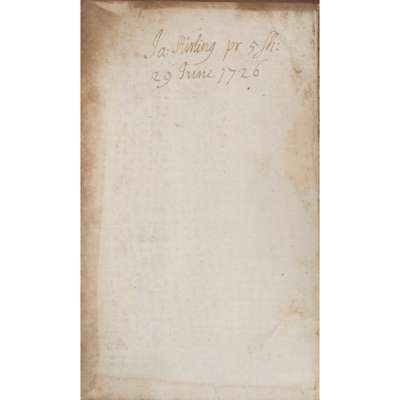

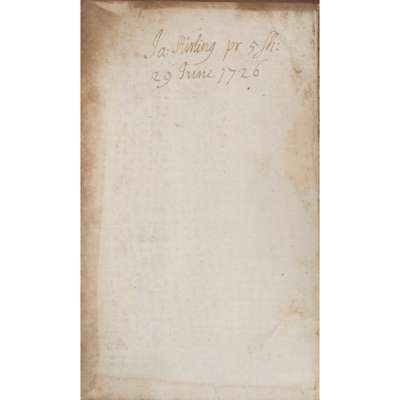

Third edition, with James Stirling's ownership inscription and dated purchase note, ‘Ja: Stirling pr 5 sh: 29 June 1726’, to the front pastedown. The third edition is the final edition published in Newton's lifetime and a reprint of the second edition of 1717, ‘save for a few corrections and the addition of one passage in the last sentence referring to Noah and his sons' (Babson).

James Stirling was a follower of Newton from his time at Oxford, where he arrived in 1710. In 1715 John Keill noted in a letter to Newton that the problem of orthogonal trajectories proposed by Leibniz had recently been solved by ‘Mr. Stirling an under-graduate here’ (Tweedie, A Sketch of his Life and Works along with his Scientific Correspondence, 1922, p. 7). Stirling's first book, Lineae tertii ordinis Neutonianae, a commentary on Newton's classification of cubic curves, was printed at the Sheldonian Theatre in April 1717, with Newton listed as a subscriber. By that time Stirling's status as a non-juring student and his alleged involvement in Jacobite agitation had already led to trouble with the university authorities, however, and his scholarships appear to have been withdrawn shortly before the book was published. Leaving Oxford without a degree, he took up an invitation to Venice from Nicolas Tron, Venetian ambassador to London. In 1719, while still in Italy and apparently in dire straits, he received much-needed financial assistance from Newton, and once back in London called on him regularly during his final years, writing in a surviving letter from 1725: ‘Sr Isaac Newton lives a little way of in the country. I go frequently to see him, and find him extremely kind and serviceable in every thing I desire, but he is much failed and not able to do as he has done’ (Tweedie, p. 13). Stirling's principal work, the Methodus differentialis, a response to Newton's paper of the same name, appeared in 1730.