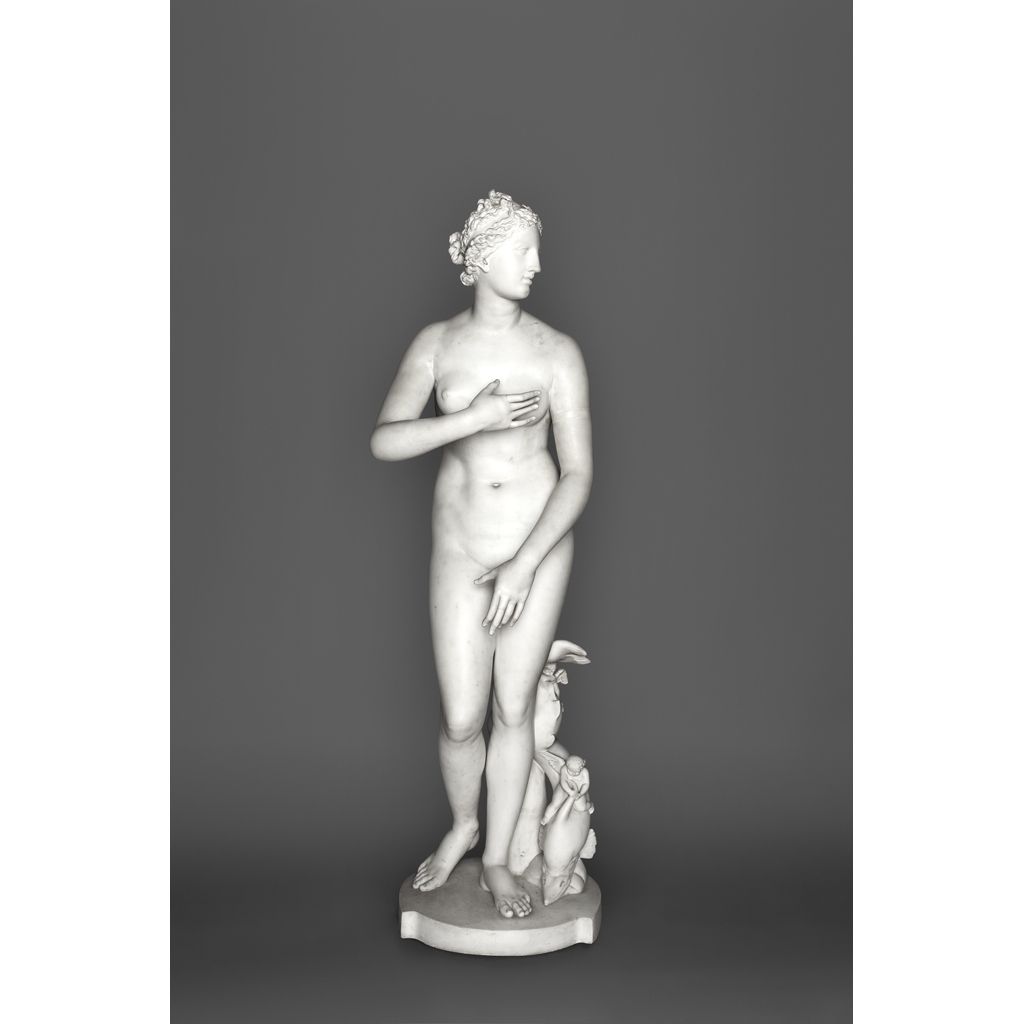

AFTER THE ANTIQUE, THE VENUS DE' MEDICI

19TH CENTURY

£35,000

Fine Furniture and Works of Art

Auction: 2 May 2018 at 11:00 BST

Description

Italian white marble

Dimensions

161cm high

Footnote

Note: This 19th century Italian version of Venus is based on the original dating to the first century AD, which was itself likely a copy of an earlier Hellenistic bronze of the Greek goddess Aphrodite. It follows in the tradition of the work of Praxiteles, the 4th century BC Greek sculptor. The goddess stands demurely, her arms seeming to cover her nakedness, as she emerges from the sea as evidenced by the dolphin at her feet.

The Venus was known to be in the Medici collection by the mid 16th century, feted as a rare survivor from the Classical period. Through the 17th century its popularity began to extend beyond the closed circles of the Italian elite, benefitted by its move from Rome to Florence in 1677, where it was installed in the Uffizi Gallery. There, Venus' provocative beauty became a prime attraction for visitors making the Grand Tour, and copies in plaster, bronze and marble were made to grace collections of those wanting to possess her.

RELATED LITERATURE

F. Haskell and N. Penny, Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture 1500-1900, New Haven/London, 1982, pp. 325-328