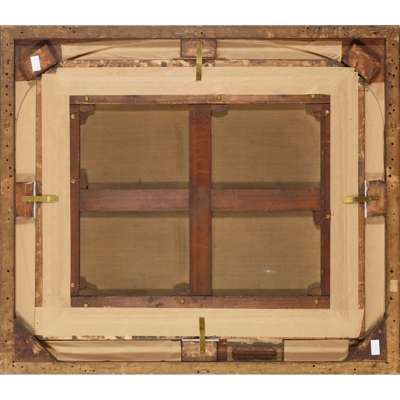

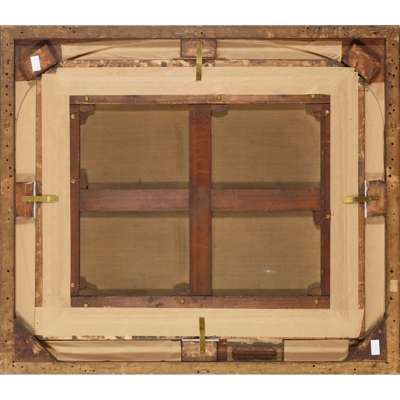

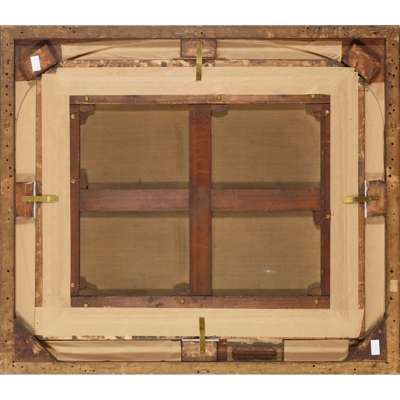

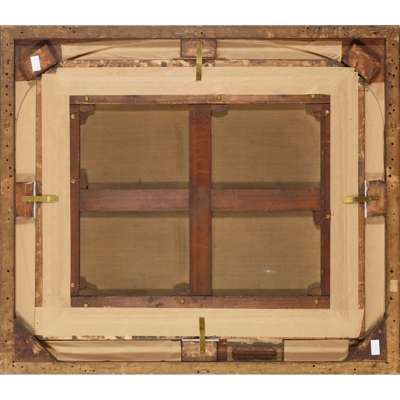

Lot 63

SIR JOSEPH NOEL PATON R.S.A. (SCOTTISH 1821-1901)

MICHELANGELO SCULPTING THE STATUE OF 'NIGHT'

Auction: 26 September 2024 from 18:00 BST

Description

Oil on canvas, arched top

Dimensions

61cm x 76cm (24in x 36in)

Provenance

Presented by A. M. McDougall, Esq., 1932.

Footnote

How is a masterpiece conceived? Sir Joseph Noël Paton invites us to ponder the very alchemy of genius by welcoming us into Michelangelo Buonarotti’s studio as he finishes carving ‘Night’. In a shadowy loggia the Renaissance artist crouches in front of his monumental marble, pausing after a campaign of chiselling to appraise his work. A spent hourglass sits on a nearby table, and a toolbox and sketchbook lie at the artist’s feet, while the view through the arch suggests that Michelangelo has taken the silhouette of Florence as his muse. The city glows blue under the light of the moon, which crests around the arch, illuminating the artist upon the completion of his masterwork.

Paton’s use of breaking light to represent ‘divine inspiration’ can be connected to the Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt’s seminal 1853 painting ‘The Awakening Conscience’ (Tate Britain). Paton had declined an invitation to join the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, electing instead to return to Scotland, but he continued to paint in a Pre-Raphaelite style and remained familiar with the Brotherhood and their output. So moved was Paton by ‘The Awakening Conscience’ that he was impelled to produce several of his own works exploring the enigma of creation and enlightenment. These include an 1861 painting of Luther who, after a sleepless night induced by a crisis of faith, is suddenly granted spiritual clarity as a ray of dawn sun touches his brow (National Galleries of Scotland), as well as a painting of Dante meditating on the nature of sin beneath an apparition of two adulterous lovers from his Divine Comedy (Bury Art Museum). In the 1860s Paton produced a further painting of Michelangelo in contemplation, which was gifted to the William Morris Gallery in 1935 from the collection of Sir Frank Brangwyn.

It might be conjectured that Paton’s interest in the nature of creative conception has something to do with the fact that he received little formal artistic training. At the age of seventeen he took his first job as Head Designer at a muslin manufacturer in Paisley, and after working in this capacity for three years, he briefly studied at the Royal Academy Schools in London, where he formed a lifelong friendship with John Everett Millais. (Rodger, Robin. “The Patons of Dunfermline: Bi-Centenary of Sir Joseph Noël Paton RSA (1821-1901).” Royal Scottish Academy, December 10 2021. [accessed 24th July 2024]). By all accounts, Paton was an expert on folklore and fairytale, themes which inspired many of his paintings and brought him considerable success and renown.

In 1861 Paton travelled to Italy, where he likely beheld Michelangelo’s ‘Night’ in the Medici Chapel in San Lorenzo, Florence. Upon his return, Paton published a book of poetry which included ‘A Confession’, a tongue-in-cheek reflection on Michelangelo’s art, so majestic as to drive the viewer to distraction:

No, Buonarotti, thou shalt not subdue

My mind with thy Thor-hammer! All that play

Of ponderous science with Titanic thew

And spastic tendon - marvellous, ‘tis true! -

Says nothing to my soul. Thy “terrible way”

Has led enow of worshippers astray;

I will not walk therein!

(Sir Joseph Noël Paton, Poems by a Painter, William Blackwood, Edinburgh, 1861, p.156)