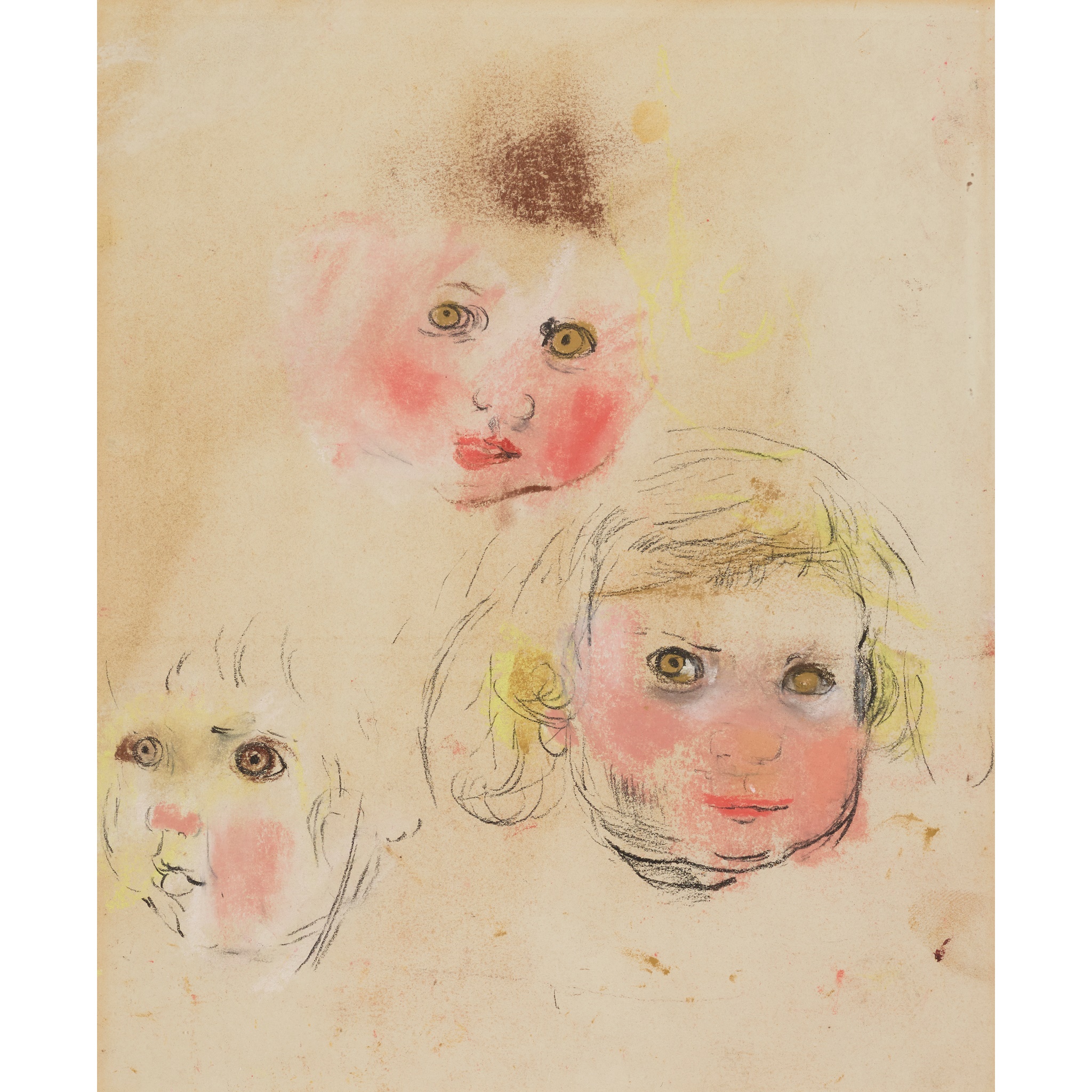

Lot 174

JOAN EARDLEY R.S.A. (SCOTTISH 1921-1963) §

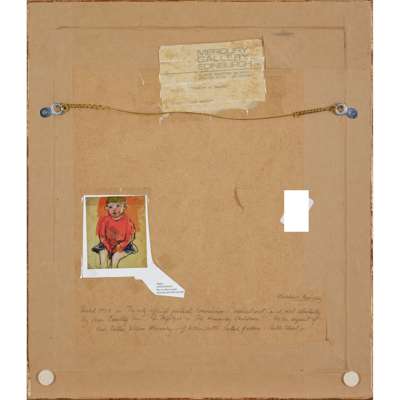

STUDIES OF AMANDA

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture

Auction: Evening Sale: 08 June 2023 | From 18:00

Description

Pastel on coloured paper

Dimensions

25.5cm x 20.5cm (10in x 8in)

Provenance

Exhibited: Mercury Gallery Ltd, Edinburgh

Footnote

Note: The Townhead district of Glasgow and the fishing village of Catterline, on the north-east coast of Scotland, provided the locations and communities which inspired much of Joan Eardley’s oeuvre, revealing her deep sense of place and people in works which have secured her a leading place in British art history.

As Fiona Pearson has explained:

Eardley was a strong, passionate painter who was totally engaged in depicting the life forces around her, everything from children to nature…Eardley’s deep love of humanity was manifest in images of the resilience of the human spirit among the poor, the old and the very young…[She reminds…] Scots of lost tenement communities and the wild natural beauty of the landscape. (Fiona Pearson, Joan Eardley, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2007, pp.8-9)

In 1953 Eardley moved into a studio at 204 St James Road in Townhead, above a scrap-metal merchant’s premises. The area was of mixed residential and light industrial use, was rundown and overcrowded, yet she was drawn to its vibrancy, declaring:

I like the friendliness of the back streets. Life is at its most uninhibited here. Dilapidation is often more interesting to a painter as is anything that has been used and lived with – whether it be an ivy-covered cottage, a broken farm-cart or an old tenement. (As quoted in Patrick Elliott and Anne Galastro, Joan Eardley: A Sense of Place, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh, 2016, p.14).

Eardley became a familiar figure sketching and photographing in the streets, drawn to the games and squabbles of the neighbourhood’s children and to evidence of lives lived in and amongst its decaying architecture. She worked spontaneously, at speed and often on the modest scale afforded by pocket sketchbooks, using larger sheets, chalks and pastels when developing imagery on return to her studio.

Works such as Children Playing Marbles (Lot 166) show how Eardley instinctively empathised with childhood emotions, as a group of youngsters are absorbed in the drama of a competitive game. In The Blue Pinafore (Lot 167) a child is caught in moment of contemplation. Her facial expression is depicted with tenderness and her unselfconscious pose speaks of innocence, whilst the thick application of pastel – sometimes highly coloured – signifies form and the artist’s energetic technique.

As Eardley became known in Townhead, so her natural rapport with the local children developed and some came to her studio to sit for her. She recalled:

Most of them I get on with…some interest me much more as characters…they don’t need much encouragement: they don’t pose…they are completely uninhibited and they just behave as they would among themselves…They just let out all their life and energy they haven’t been able to at school. (As quoted in Elliott and Galastro, op.cit., p.48)

The studio works could be more considered, as seen in Studies of Amanda (Lot 174) and Portrait Study (Lot 173). Boy with Blue Trousers (Lot 172) shows the ease at which she put her sitters, a whirlwind of lines applied over colour fields to define his features, his gap-toothed smile revealing his age and good humour. As a son of Eardley’s dealer, Bill Macaulay of The Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh, Eardley will have known the boy well.

Two Children (Lot 169) is a particularly resolved and successful work. Skilful layering and blending of multi-coloured pastels focus attention on the children’s faces, their overlapping pose suggesting the intimacy of siblings. Eardley’s gestural technique communicates the patterning of their clothing, which gives way to free form mark-making.

Ginger (Lot 170) is a dignified yet tender portrait. Executed with oil on board, the boy looks directly at the artist (and by extension the viewer). As Christopher Andreae has written about such works:

They were portraits not caricatures. She had too much rapport with them for such distortion. And direct, daily experience of them actually meant she knew them well and painted them in their world…she [did not]…let sentimentalism sift sugar over her understanding of these kids. (Christopher Andreae, Joan Eardley, Farnham 2013, p. 127)