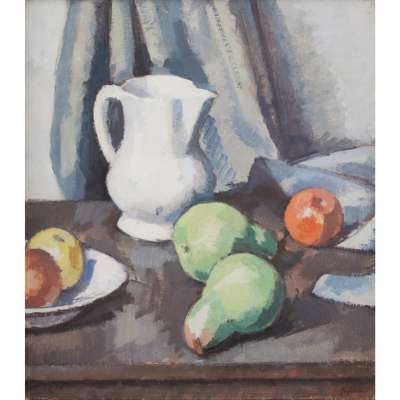

Lot 162

SAMUEL JOHN PEPLOE R.S.A. (SCOTTISH 1871-1935) ◆

STILL LIFE WITH WHITE JUG AND PEARS

Scottish Paintings & Sculpture

Auction: Evening Sale: 08 December 2022 | From 18:00

Description

Signed, oil on canvas

Dimensions

18in x 16in (45.7cm x 40.7cm)

Provenance

Provenance: Sotheby’s Gleneagles, Scottish and Sporting Pictures and Sculpture, 2 September 1998, lot 1479, as ‘Still Life with Pears (The White Jug)’

Portland Gallery, London

Exhibited: London, Portland Gallery, The Scottish Colourists, 14 June-19 July 2002, no.52

London, Portland Gallery in association with The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh, S. J. Peploe (1871-1935), 7-29 November 2012, no.18, Ill.col.p.29.

Footnote

Still Life with Jug and Pears of c.1925 reveals Peploe’s mastery of the still life genre, which came to maturity in his practice during the 1920s. He summed up his dedication to the theme, even beyond the landscapes and portraits for which he is also celebrated, in 1929, when he declared: ‘there is so much in mere objects, flowers, leaves, jugs, what not – colours, forms, relation – I can never see mystery coming to an end.’[i]

The still life was the primary focus of the work made in his longest-serving studio, at 54 Shandwick Place in Edinburgh’s West End. Peploe moved there in 1917 after it was vacated by his friend, the artist James Paterson and maintained it until a move to nearby Castle Street in 1934. The Director of the National Galleries of Scotland, Stanley Cursiter, described it thus: ‘the room had a large, high and well-placed window. The scheme of decoration was…kept in a very light key and he surrounded himself with brilliant colours.’[ii]

As Roger Billcliffe has explained: ‘Peploe set himself as a target the perfect still-life painting. It had been his first love and his first serious achievements had been in still-life. His temperament made him ideally suited to the task. His calm reasoning and thoughtful manner enabled him to make a careful analysis of the problems which face the still-life painter and he set about resolving them.’[iii]

A sense of this dedication is clear in a description of visiting Peploe in his studio by his niece, Margery Porter: ‘How well I recollect my Mother and myself climbing those steep stairs and arriving panting at the top to ring his bell in fear and trembling lest our climb had been in vain. But usually he would usher us in wearing a white painting coat and a crownless hat…The studio was a large one, round which I would prowl entranced, after strict warnings not to disturb the still-life group which would almost inevitably be covering the table. My uncle would arrange and re-arrange these groups for perhaps three days before he was satisfied that the balance and construction were perfect, then he would paint them quite rapidly.’[iv]

Alongside a cast of cherished objects, including jugs, plates, bowls and various lengths of fabric, Peploe would introduce flowers or fruit to his still lifes according to the season. The apples and pears of Still Life with Jug and Pears would suggest that it is an autumnal painting. This caused some consternation amongst the purveyors of such produce, as explained by Cursiter: ‘When he selected his flowers or fruit from a painter’s point of view he presented a new problem to the Edinburgh florists. They did not always understand when he rejected a lemon for its form or a pear for its colour and he remained unmoved by their protestations of ripeness or flavour.’[v]

Still Life with Jug and Pears contains all the hallmarks of Peploe’s work of the mid-1920s as he developed from the highly-complex and high-pitched still lifes of earlier in the decade and progressed towards the more raw and expressive style of the early 1930s. There is an overall feeling of dignity in the arrangement, subtle palette and natural lighting of this painting. The depiction of the pears in the foreground is a masterclass in perspective, whilst the warm tones of the apple to the right provide the colour focal point of the composition.

Peploe’s enduring interest in the work of Paul Cézanne is clear, for example in the strength of form created by defined planes of colour, particularly in the fruit. Deliberately distinct brushstrokes convey shadow and reflection. The arrangement of objects is asymmetrical yet perfectly balanced, presided over by the jug. The edge of the table on which they are presented is aligned to the lower horizontal plane of the canvas, as Peploe skilfully plays with notions of reality and representation. Moreover, the cropping, such as of the dish on the left, suggests the space beyond the table and the frame.

Peploe was to explore these concerns further in works such as the related and slightly later Still Life with Jug and Grapes (The Courtauld, London, acc.no. P.1992.XX.1). In this painting, the same jug has taken centre stage in the foreground, drapery plays a more significant role on the table-top and Peploe has extended the sense of distance by including a covered chair in the background. The poise and classical simplicity of Still Life with Jug and Pears has given way to a less polished vigour.

Still Life with Jug and Pears dates from a particularly propitious period in Peploe’s career. During the 1920s his reputation was cemented in Scotland and spread to London, Paris and New York. He had regular solo exhibitions at The Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh and La Société des Beaux-Arts in Glasgow. When the latter business merged with the Lefèvre Gallery in London in 1926, Peploe’s work was also shown there.

In 1923, paintings by Peploe, Cadell and Hunter were shown at the Leicester Galleries in London and again in 1925, joined by the work of John Duncan Fergusson. The four artists were celebrated in an exhibition at the Galerie Barbazanges, Paris in 1924, from which a painting by Peploe was acquired for the French national collection. In 1927, he was elected a full member of the Royal Scottish Academy and the Tate acquired one of his still lifes, meaning that he was represented in the British national collection. In 1928 a solo exhibition of his work was staged at the C. W. Kraushaar Galleries, New York and a room was dedicated to his work in the newly extended Kirkcaldy Museum and Art Gallery.

Corsan Morton, Curator at Kirkcaldy, summed up Peploe’s achievements of the period in his catalogue foreword: ‘It is in his still lifes, his arrangements of flowers, fruit, utensils and so on, that he has of late years achieved a very definite personal style of great beauty, which places him in a class by himself…He handles with distinction everything he touches.’[vi]

[i] As quoted in Stanley Cursiter, Peploe: An Intimate Memoir of an Artist and of his Work, Edinburgh 1947, p.73.

[ii] Cursiter, op.cit., p. 41.

[iii] Roger Bilcliffe, The Scottish Colourists: Cadell, Fergusson, Hunter, Peploe, London 1990, p.51.

[iv] As quoted in Alice Strang et al, S. J. Peploe, Edinburgh 2012, p.23.

[v] Cursiter, ibid., p.55.

[vi] As quoted in Cursiter, ibid., p.63.