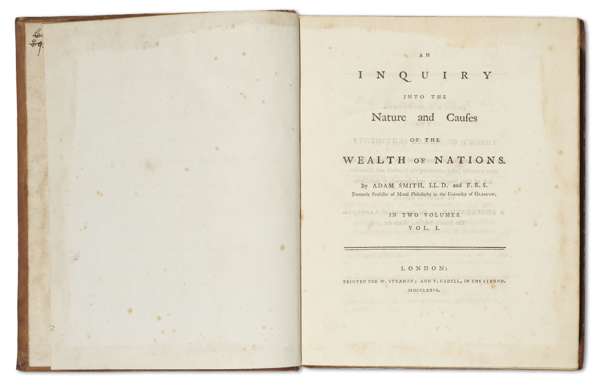

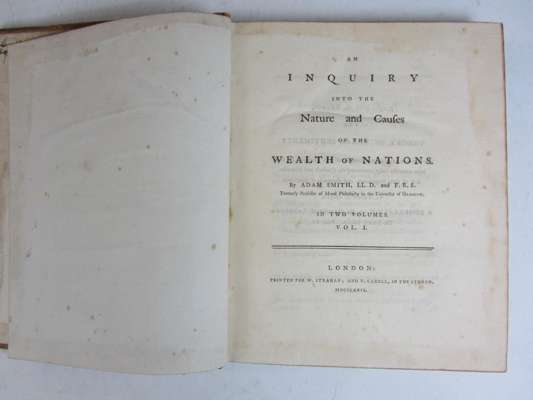

Lot 287

Smith, Adam

Rare Books, Maps & Manuscripts

Auction: 4 September 2013 at 12:00 BST

Description

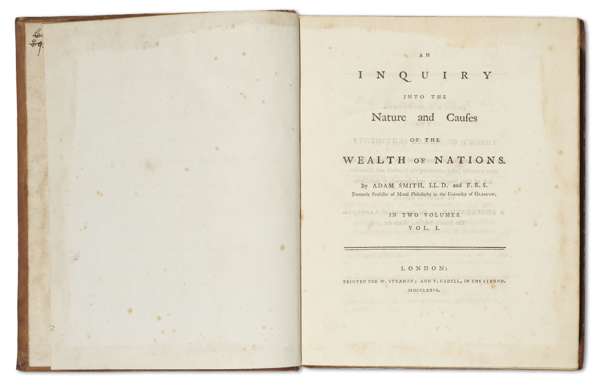

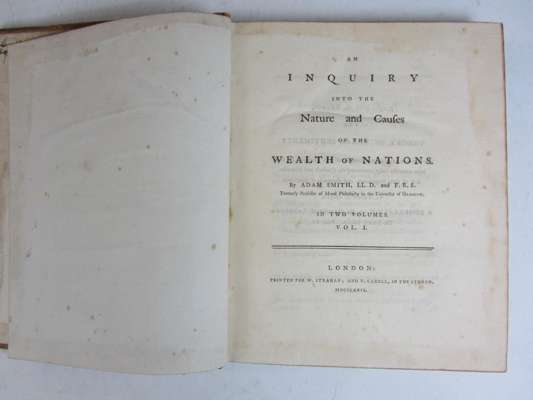

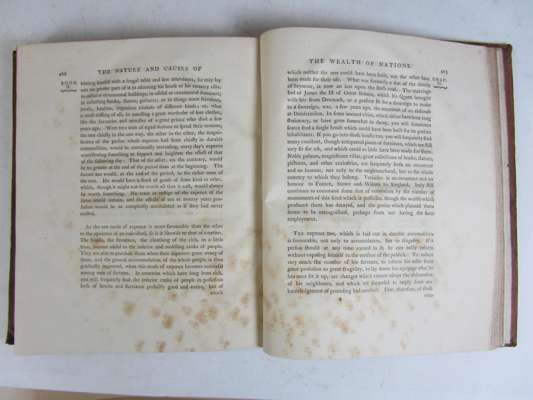

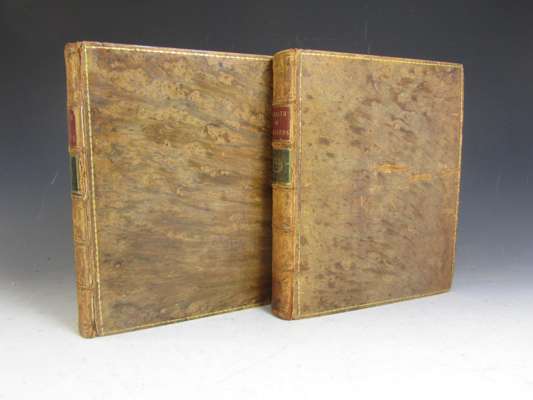

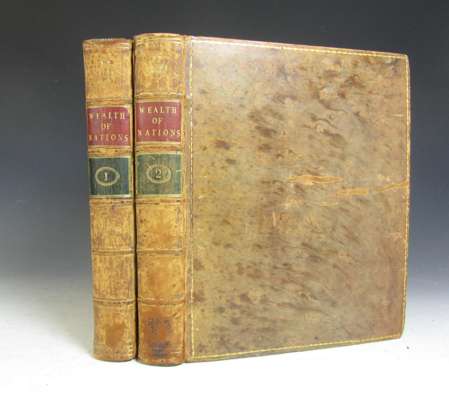

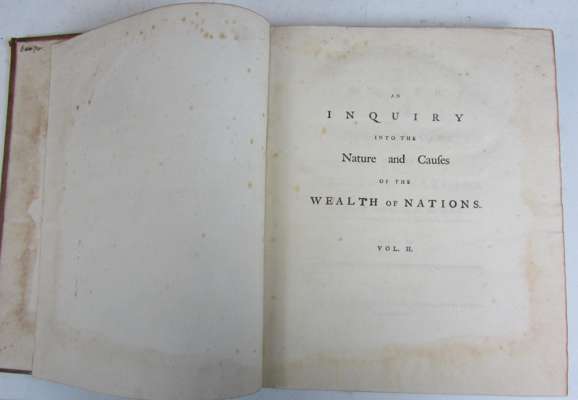

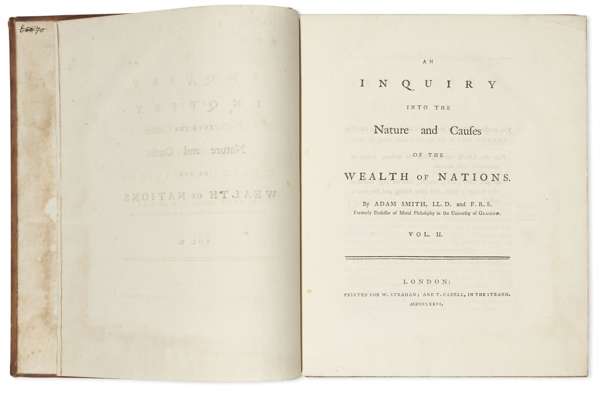

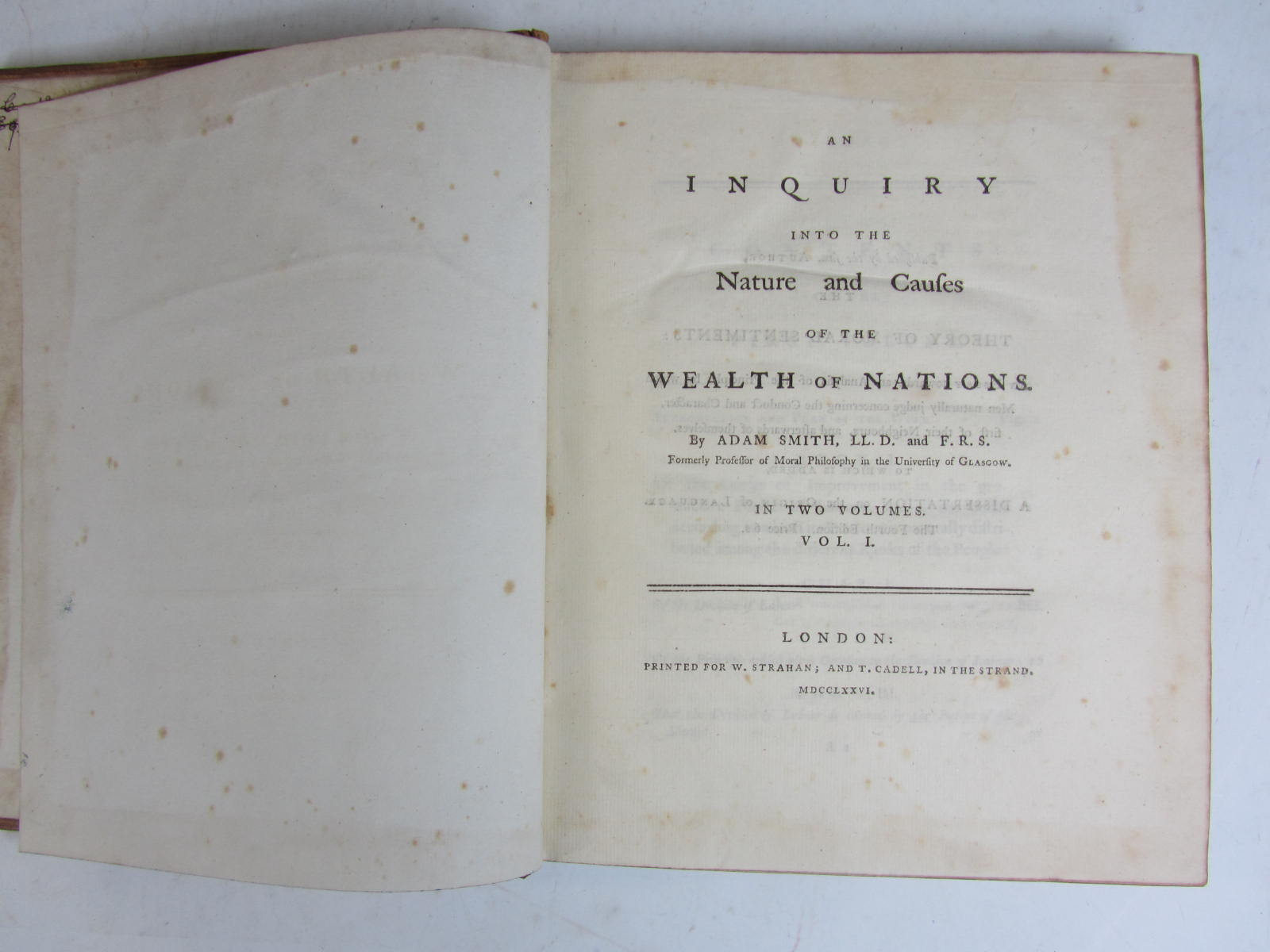

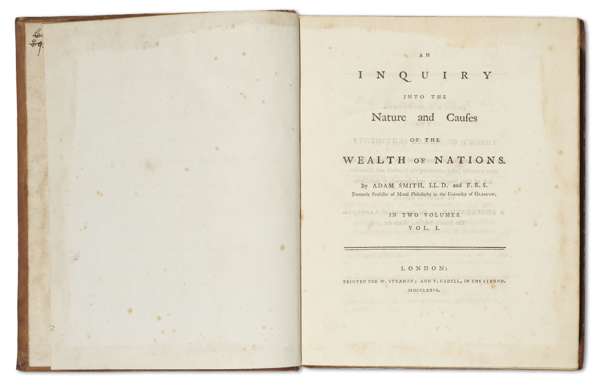

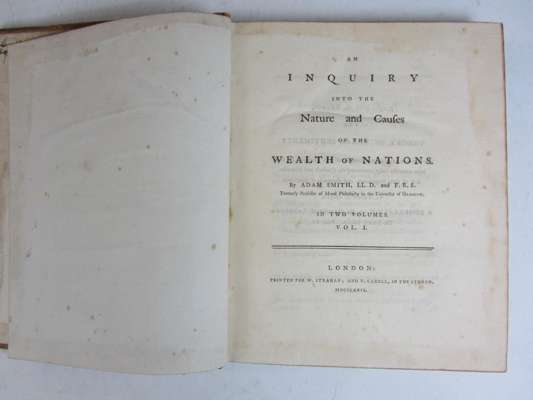

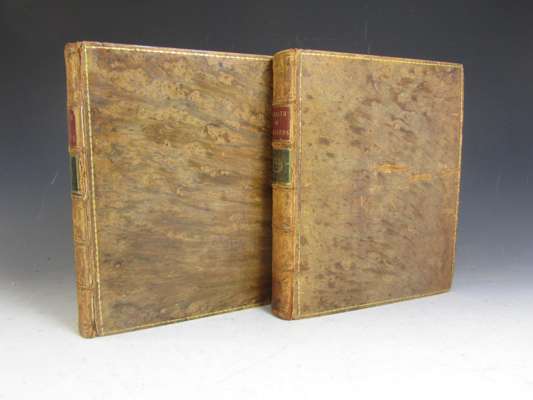

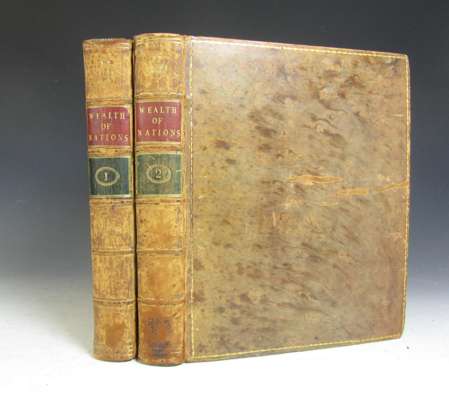

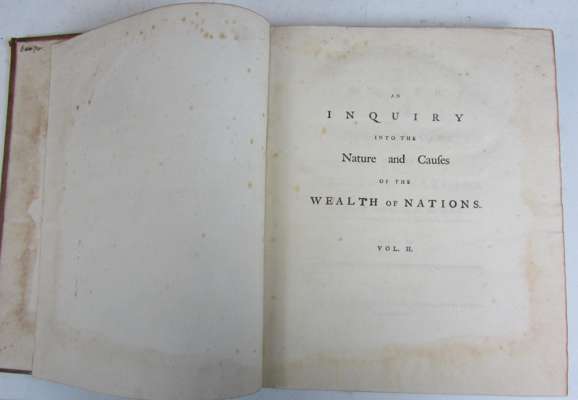

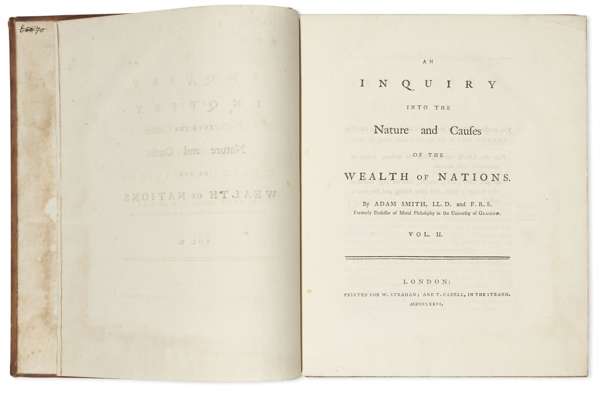

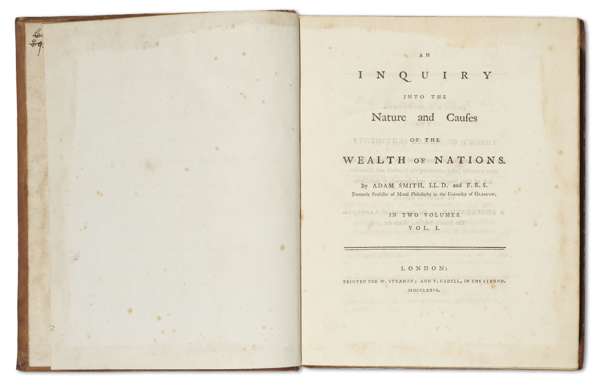

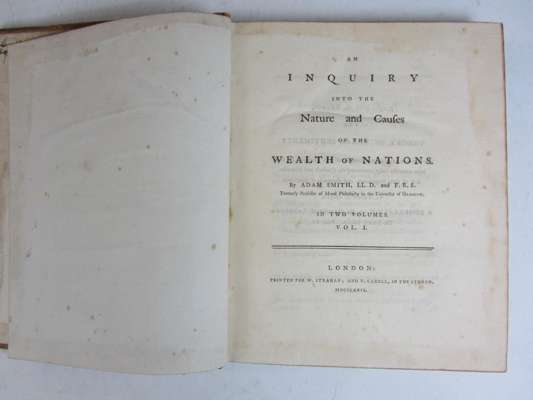

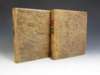

An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. London: for W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776. First edition, 2 volumes, 4to, (276 x 220mm.), half-title in volume 2 only as issued, with cancels M3, Q1 U3, 2Z3, 3A4 and 3O4 in vol. I and D1 and 3Z4 in vol. II, contemporary tree calf, with final blank in volume 1, some spotting, slight marginal discolouration to title of volume 1 and half-title of volume 2, head of spines worn, upper cover of volume 1 detached, lower joint of volume 2 split

Footnote

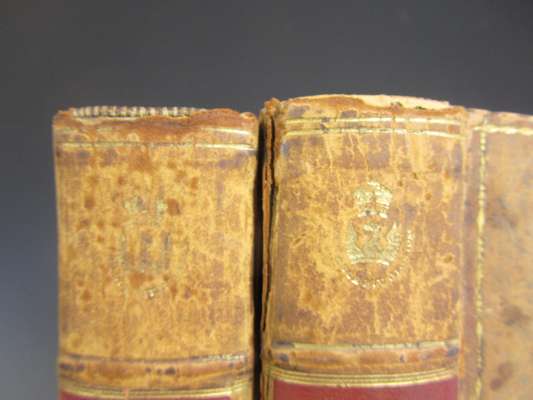

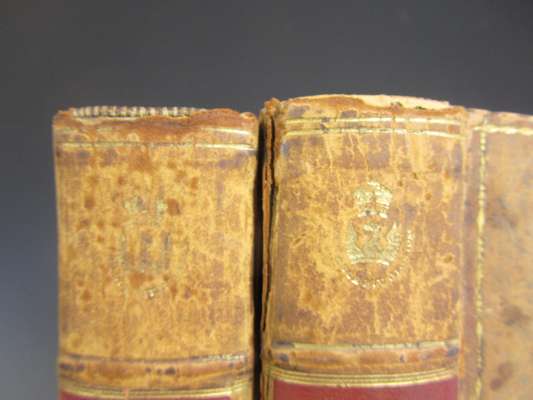

Provenance: Erskine, James St Clair, 2nd Earl of Rosslyn (1762 - 1837) - crest at head of spines with motto "Rinasce piu gloriosa"

Note:

Adam Smith (1723-1790) was not only one of Scotland's greatest moral philosophers but also a pioneer of political economy. One of the key figures of the Scottish Enlightenment, Adam Smith is best known for two classic works: The Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) and An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776). The latter is considered his magnum opus and the first modern work of economics. Smith is cited as the "father of modern economics" and The Wealth of Nations is still considered a fundamental work in classical economy.

Smith was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, entered the University of Glasgow when he was fourteen and studied moral philosophy under Francis Hutcheson. Here, Smith developed his passion for liberty, reason and free speech. After a brief spell at Oxford University, Smith began delivering public lectures in 1748 in the University of Edinburgh under the patronage of Lord Kames, on the topics of rhetoric and belles-lettres and, later, the subject of "the progress of opulence".

In 1750 he met the Scottish philosopher David Hume who became a close friend, the two sharing wide intellectual interests. In 1751 Smith was given a professorship at Glasgow University and in 1752 was appointed head of Moral Philosophy. His seminal work, The Theory of Moral Sentiments was published in 1759, and centred on how human morality depends on sympathy between agent and spectator, or the individual and other members of society, Smith defining "mutual sympathy" as the basis of moral sentiments.

After a spell abroad tutoring Henry Scott, the young Duke of Buccleuch, Smith returned to Kircaldy and devoted much of the next ten years to writing his magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations.

In it Smith challenged the prevailing mercantilist economic philosophy, in which people saw national wealth in terms of a country's stock of gold and silver and imports as a danger to a nation's wealth, arguing that in a free exchange both sides became better off. Quite simply, nobody would trade if they expected to lose from it. The buyer profits, he argued, just as the seller does. Imports are just as valuable to us as our exports are to others.

Because trade benefits both sides, Smith argued, it increases our prosperity just as surely as do agriculture or manufacture. A nation's wealth is not the quantity of gold and silver in its vaults, but the total of its production and commerce - what today we would call gross national product.

The Wealth of Nations deeply influenced the politicians of the time and provided the intellectual foundation of the great nineteenth-century era of free trade and economic expansion. Even today the common sense of free trade is generally accepted worldwide, whatever the practical difficulties of achieving it.

Smith also espoused a radical, fresh understanding of how human societies actually work. He realised that social harmony would emerge naturally as human beings struggled to find ways to live and work with each other. Freedom and self-interest need not produce chaos, but - as if guided by an 'invisible hand' - order and concord. And as people struck bargains with each other, the nation's resources would be drawn automatically to the ends and purposes that people valued most highly.

It followed that a prospering social order did not need to be controlled by kings and ministers. It would grow, organically, as a product of human nature. It would grow best in an open, competitive marketplace, with free exchange and without coercion.

The Wealth of Nations was therefore not just a study of economics but a survey of human social psychology: about life, welfare, political institutions, the law, and morality.