Lot 92

![Mattioli, Pietro Andrea [Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun]](https://media.app.artisio.co/media/104cbde6-0d38-43cb-9e0f-bb721ef57bcf/inventory/97aa0724-17bd-42aa-bc2c-2f0006b0be46/f345e6e9-e146-4aed-8541-491acecb9cc4/0001_lgwkRx_original.jpg)

Mattioli, Pietro Andrea [Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun]

Commentarii in sex libros

Rare Books, Manuscripts, Maps & Photographs

Auction: 13 July 2022 from 10:00 BST

Description

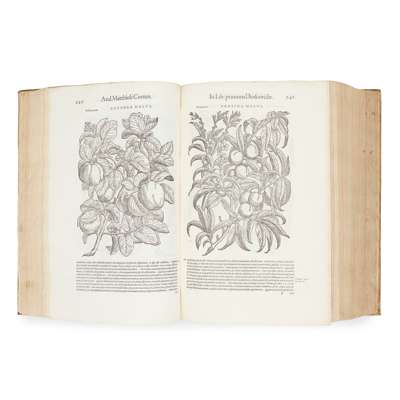

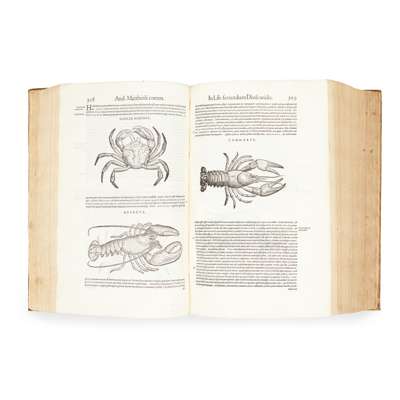

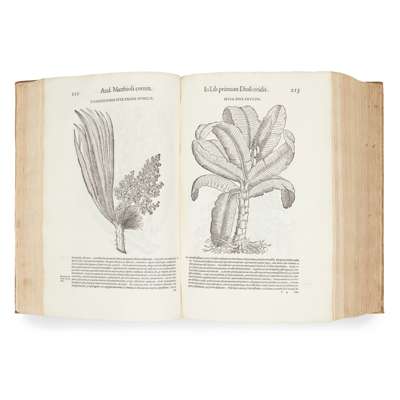

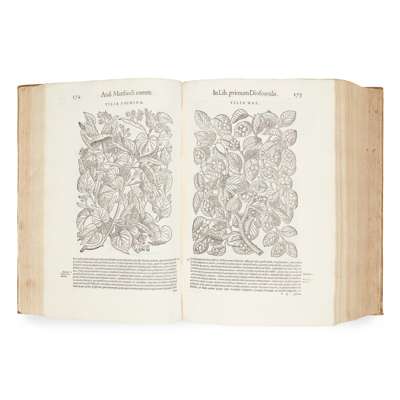

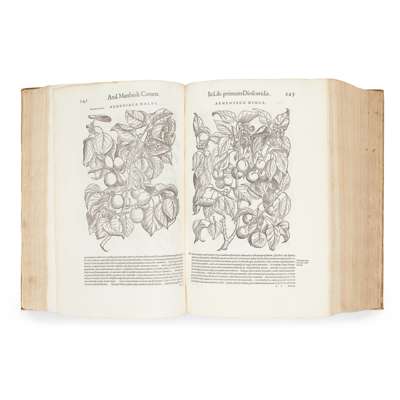

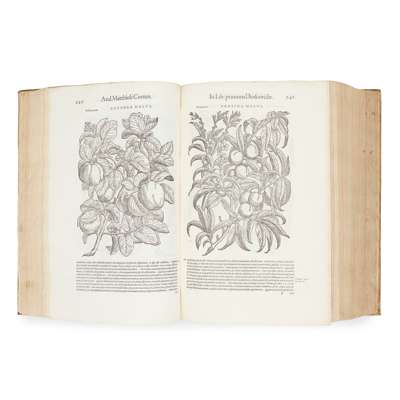

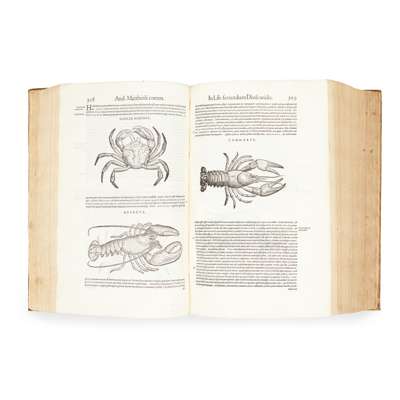

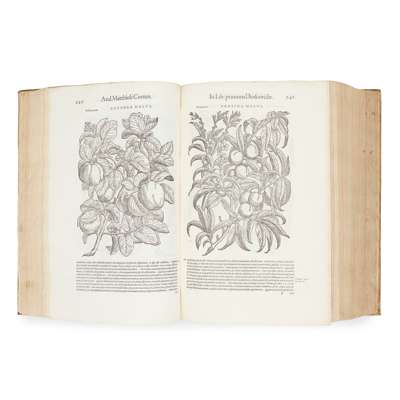

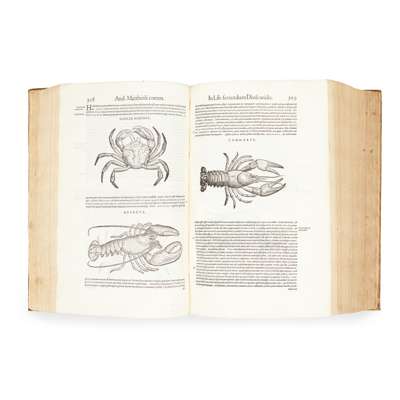

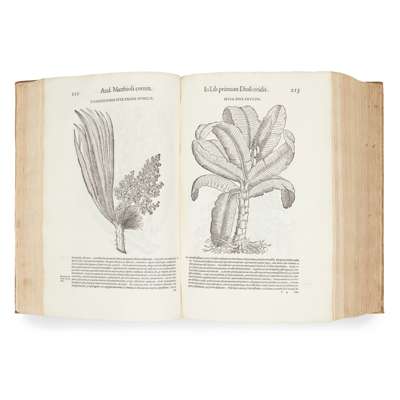

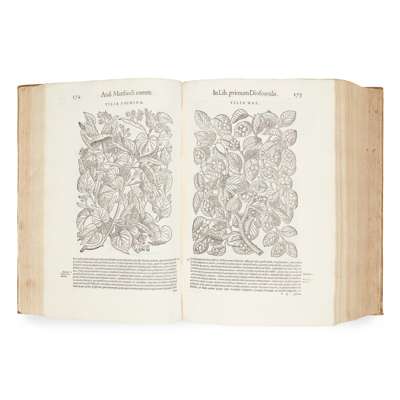

Venice: Vincenzo Valgrisi, 1565. Folio (363 x 245mm), [86] leaves, 1459, [1] p., [6] leaves; full-page woodcut portrait of Mattioli, numerous page-width woodcut illustrations of plants, flowers and animals, woodcut printer's device on title-pages and final verso, woodcut initials, contemporary vellum with manuscript title to spine, bookplate reading 'GOM' to paste-down endpaper, early ownership signature of Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun to title-page, a few very neat annotations to index in an early hand, ties lacking, covers a little soiled

A tall fine copy of the monumental edition of the most important medico-botanical encyclopaedia of the sixteenth century

Footnote

Note: "First enlarged edition... the 1565 edition is the first augmented by Mattioli's fuller notes and has always been the most valued for its completeness" (Hunt). Although Mattioli wrote on a range of subjects, and published translations of non-medical works, he is most celebrated for his work on botany and medicine, and of these works his best known are his translations of, and commentaries on, Dioscorides' De medica material.

Mattioli's first Italian translation from the Greek was published in Venice in 1544, and its 'original purpose was relatively modest: it was to provide doctors and apothecaries with a practical treatise in Italian with a commentary that would enable them to identify the medicinal plants mentioned by Dioscorides' (DSB IX, p.179). Further, expanded editions followed in 1548, 1550 and 1552, and the success of these editions, led Mattioli to translate the work into Latin in 1554. This translation was "enriched by synonyms in various languages, provided with a special commentary, and accompanied by numerous illustrations valuable for the identification of Dioscorides simples [which] rendered the work accessible to scholars throughout Europe. From then Mattioli's name was linked with that of Dioscorides" (DSB IX, p.179).

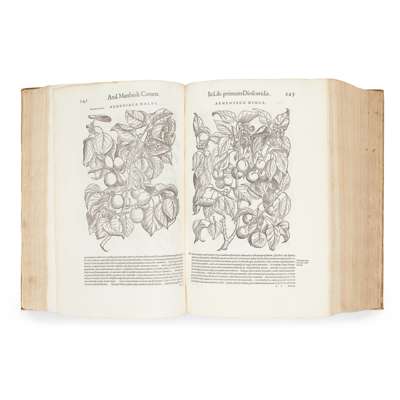

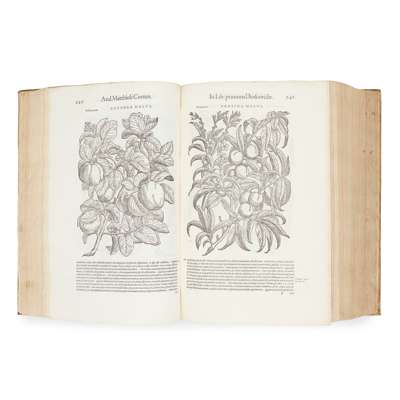

In addition to identifying the plants originally described by Dioscorides, Mattioli added descriptions of some plants not in Dioscorides and not of any known medical use, thus marking a transition from the study of plants as a field of medicine to a study of interest in its own right. In addition, the woodcuts in Mattioli's work were of an extremely high standard, allowing recognition of the plant even when the text was obscure. A noteworthy inclusion is an early variety of tomato, the first documented example of the vegetable being grown and eaten in Europe.

This wealth of additional material transformed Dioscorides' work from an antiquarian text into a contemporary physician's vade mecum, enhanced by Mattioli's own observations and many of his own drawings, which remained in print virtually continuously until the 18th century.

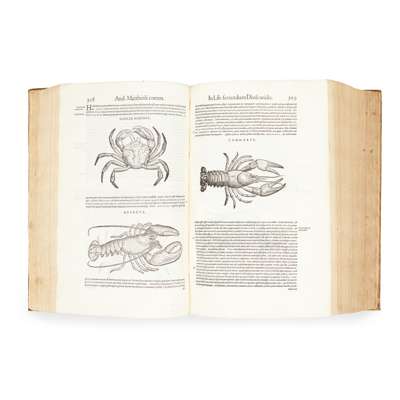

The 1565 edition, described by Brunet as 'la plus estimée', is considered the best for both its illustrations (first used here in a Latin edition), and text. The fine woodcut illustrations extend across the full width of the page: those of plants are by Giorgio Liberale and Wolfgang Meyerpeck (originally cut for Mattioli's New Kretterbuch (Prague: 1563), with the exception of 'Eruca sylvestris') and 'those of the Animals are new' BM(NH). Reference: Hunt 94.

Provenance: Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun. The library of Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun (1653-1716) was the largest private collection of books in Scotland at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It is significant both in itself and because of the life of its owner. Of a legal and landed family - the estate of Saltoun lay not far from Edinburgh in the fertile country of East Lothian - Andrew Fletcher is famous in his own country as a consistent and eloquent opponent of the Union with England in 1707, a stance for which he became known as "the Patriot". But he was also a political thinker of intelligence and originality, author of a series of tracts on militias and standing armies, on the economic and social condition of Scotland, on the issues facing the Scottish parliament before the Union, and, more generally, on the political prospects of Europe and its smaller states in particular in the face of the ambitions of Louis XIV. Informing both his political and his literary activity was a lifetime of travel, much of it in the Netherlands (and some of it in enforced political exile), but extending to France, Spain and Germany, and possibly further afield still (Fletcher spoke and wrote Italian). It was almost certainly on these travels that Fletcher acquired the greater part of his library.

[Willems, P.J.M. Bibliotheca Fletcheriana, or the Extraordinary Library of Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun, Reconstructed and Systematically Arranged. Wassennar, 1999]