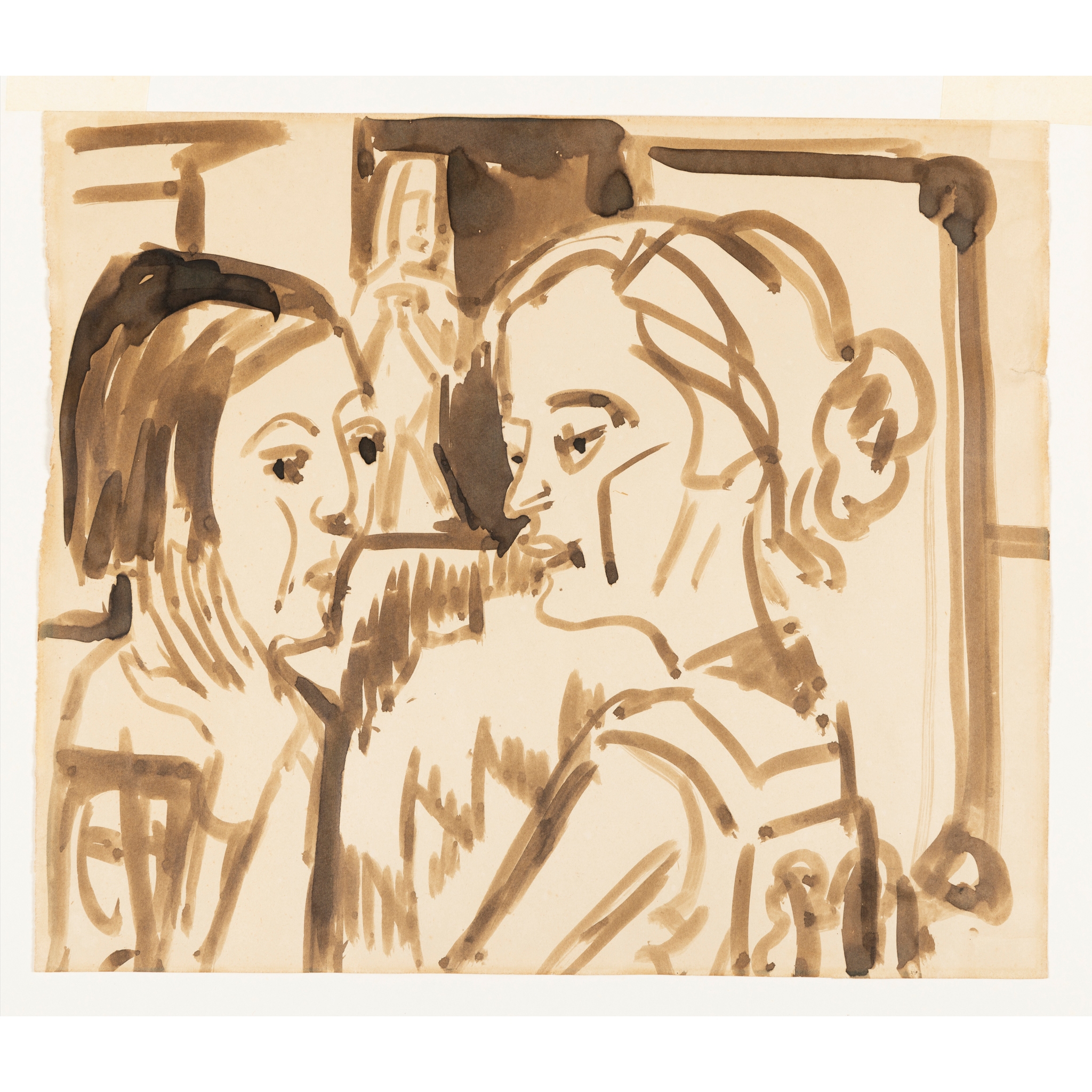

Lot 33

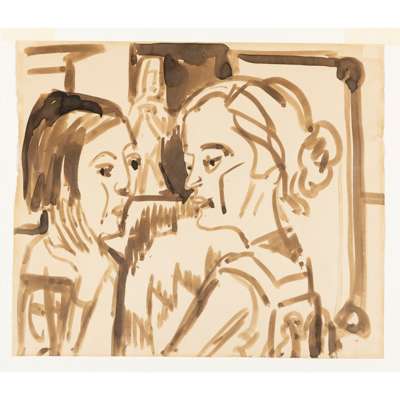

ERNST LUDWIG KIRCHNER (GERMAN 1880-1938)

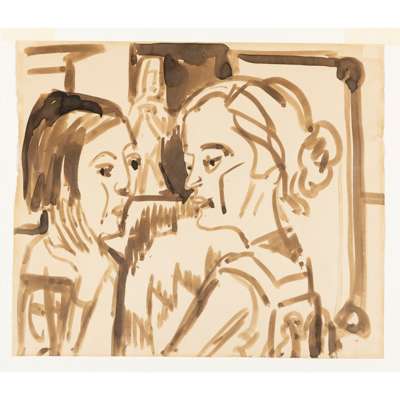

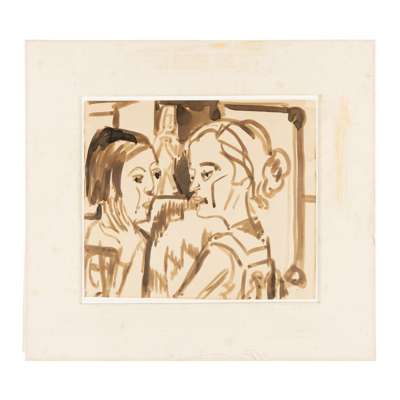

ZWEI FRAUEN IM GESPRÄCH [TWO WOMAN IN CONVERSATION], c. 1921

Auction: The Gillian Raffles Collection Evening - Lots 1 to 73 - Thursday 01 May at 18:00

Description

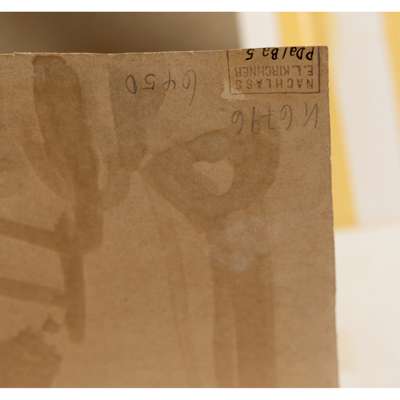

stamped with the Nachlass E. L. Kirchner mark and numbered P Da/Ba 5 in ink and K6796 and 6450 in pencil (to reverse), Indian ink and wash on paper

Dimensions

30.2cm x 36cm (11 7/8in x 14 1/8in)

Provenance

Theo Hill Galerie, Cologne, 1968;

Anthony Hepworth FIne Art, Bath;

The Collection of Gillian Raffles.

Footnote

This work is listed in the Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Archives, Wichtrach/Bern and will be included in any forthcoming catalogue raisonnés of the artist's graphic works,

Exhibited:

Mercury Gallery, London, Summer Exhibition, 11 June - 15 September 1973, no. 191, illustrated in exhibition catalogue.

‘I learnt to value the first sketch, so that the first sketches and drawings have the greatest worth for me. How often I’ve failed to pull off and consciously complete on the canvas that which I threw off without effort in a trance in my sketch…’

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, ‘Zebdher Essay’, recorded in his diary, 1927

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner’s Zwei Frauen im Gesprach is the perfect expression of the ‘modernist primitivism’ that defined German Expressionism in the early 20th Century, both that of the Die Brücke group (of which Kirchner was the founder and leading light) and its Munich counterpart, Der Blaue Reiter, led by Kandinsky. Both groups sought to free art – and life – from the shackles of bourgeois ideals and (in art) stifling Academism, alighting upon the cultures of non-European peoples as ciphers of a more direct and intuitive emotional ‘truth’, in particular the art of the Pacific (inspired by Gauguin) and of Africa. Whilst today we would look at the Expressionists’ approach to non-Europan art as a form of cultural appropriation, based on fundamental misconceptions of this art being ‘primitive’ rather than highly sophisticated in its own right, this approach was, at least, wholehearted in its intention: Kirchner and his contemporaries were genuinely looking to the non-European for something lacking in the West, their ‘primitivism’ beyond a mere imitation – rather a search for authenticity, a direction of travel to express true modernity.

In Zwei Frauen im Gesprach, we see two young women in conversation in what looks like Kirchner’s studio – which itself was a gesamkunstwerk (total art work) of hand-printed batik hangings, dark painted walls, hand-carved furniture and African objects. In the background, we see one of these objects, a small totemic figure, listening in, perhaps, to what these two thoroughly modern women are discussing. The figure on the left, with her bobbed hair and arch hand gesture looks like she has stepped straight out of a Berlin cabaret. Indeed, she could well be the dancer Nina Hard, renowned for her slick black bob, whom Kirchner had met in Zürich in May 1921 and who was to became an important model and muse for him. And this sculpture in the background could well be African, brought back by the brother of fellow Die Brücke artist Erich Heckel, who held a job in colonial East Africa, but equally it could be a work of Heckel or Kirchner’s own making, as modern as the women themselves. Kirchner’s sculptures of the 1910s are incredible hybrid works, far beyond imitations of African art and distinctly European, that don’t really find their counterpart until Georg Baselitz’s chainsaw carvings of the 1980s.

In Zwei Frauen im Gesprach Kirchner shows his mastery of brush and ink, which perhaps could be said to be the medium of German Expressionism. The brush allows for bold, jagging lines and an emphasis on outline over shading, as sculpting the figures on paper as they would with chisels out of wood; and the ink allows for speed – an idea as modern as modern can be. Brush and ink allows spontaneity, a definitiveness of gesture, that Kirchner, Heckel and fellow members of Die Brücke honed in their ‘quarter-hour’ life drawing sessions, where working quickly became analogous to working without premeditation – or as Jill Lloyd puts it, speed of execution becomes an ‘attempt… to catch modernity on the wing’. (Jill Lloyd, German Expressionism: Primitivism and Modernity, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1991, p.45)