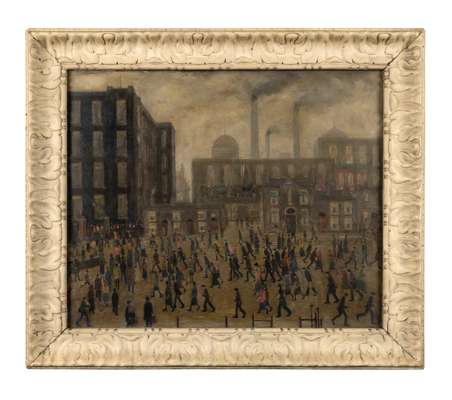

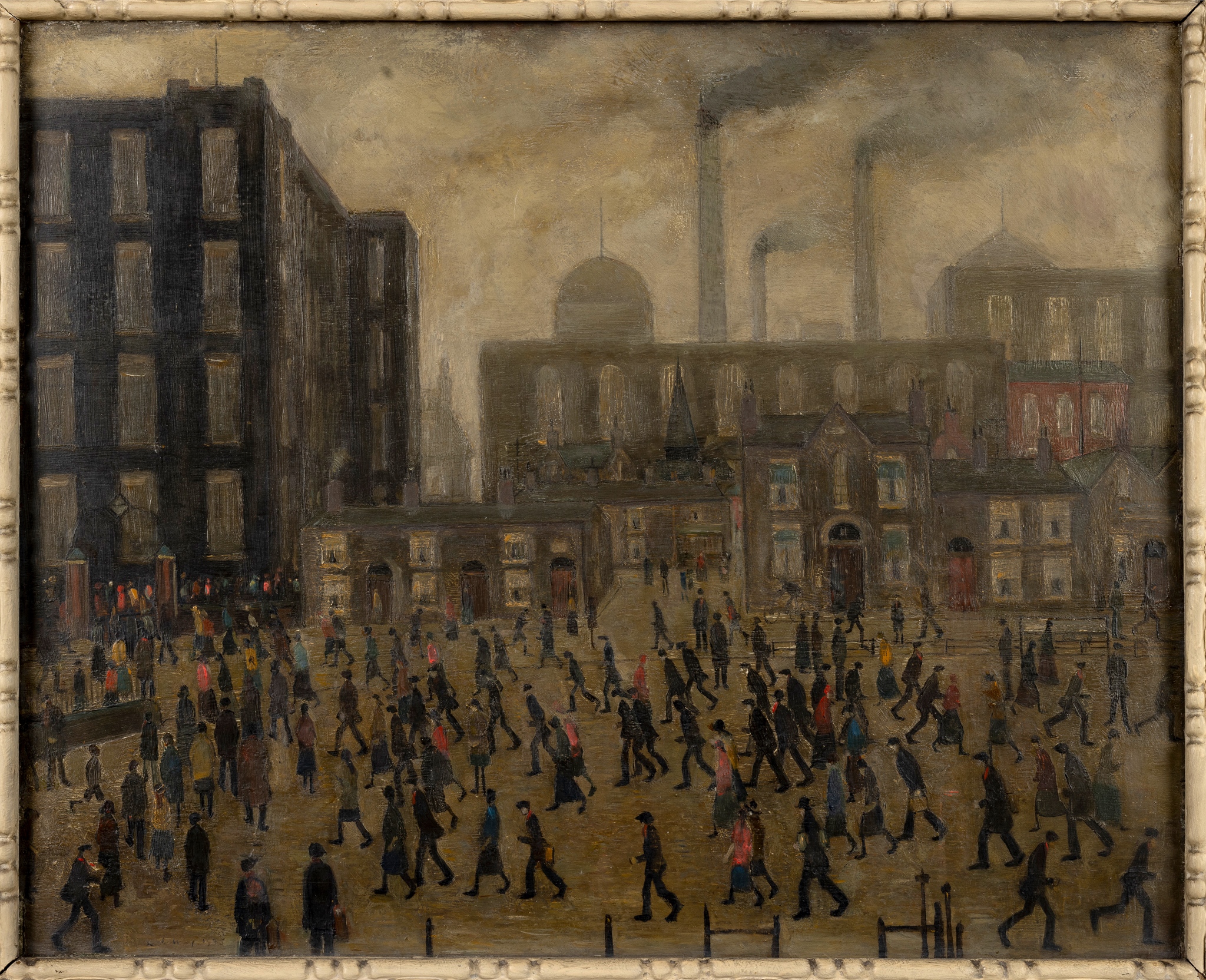

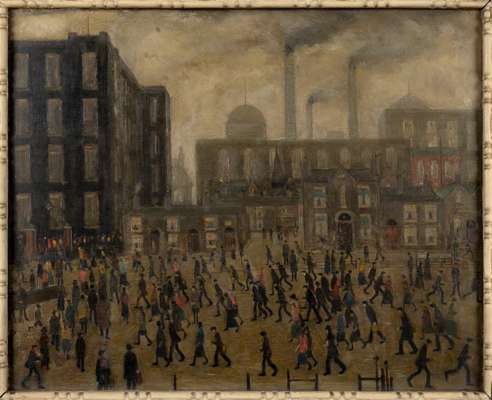

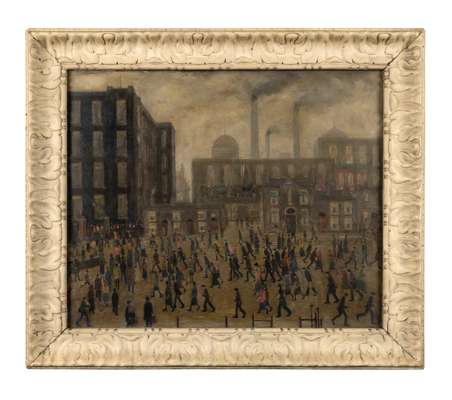

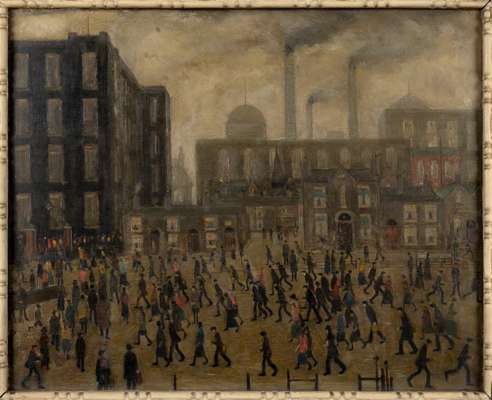

Lot 124

LAURENCE STEPHEN LOWRY (BRITISH 1887-1976) §

GOING TO THE MILL, 1925

Auction: Modern Made Day 2 - Lots 124 to 456 - Friday 02 May at 10:30

Description

signed and indistinctly dated (lower left), oil on panel [n1]

Dimensions

43.2cm x 53.4 cm (17in x 21in)

Provenance

Acquired directly from the Artist by A.S. Wallace, 1926, and thence by descent to the present owner.

Footnote

Exhibited:

On long-term loan to Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, 2013-2024

L S Lowry’s early masterpiece Going to the Mill was painted a hundred years ago and, quite remarkably, has been in the same private family collection for all but one of those hundred years. It was acquired directly from Lowry by the journalist A.S. Wallace, an editor at the Manchester Guardian who had illustrated three of Lowry’s works in the special ‘Manchester Civic Week’ supplement published by the paper. Civic Week was held from the 2nd to the 9th of October 1925, ostensibly to celebrate Manchester’s industrial success, but also with an ulterior motive to discourage the city’s disgruntled workers from going on strike. It was the grim nature of the workers’ lives that, of course, interested Lowry, but which also made it hard for him to find an audience for his visual elegies of the industrial city – a concept that is perhaps hard to fathom now, for those of us that have grown up knowing Lowry as one of Britain’s most celebrated ‘painters of modern life’. During Civic Week, Lowry’s works were displayed in Lewis’s department store, where they were mostly passed by – despite the favourable reviews the Guardian had given his first solo show in 1921. A.S. Wallace, however, fell for Lowry’s depictions of the ‘lovely, ugly town’ (to borrow from Dylan Thomas’s description of his hometown of Swansea), striking up a friendship with the artist and asking to buy one. Lowry duly obliged: Going to the Mill is marked on the back as being £30 – Lowry let Wallace have it for £10. If not his first ever sale, this has to have been one of his earliest. He also threw in an additional work - The Manufacturing Town. The Wallace family still have Lowry’s letter of 9th November 1926, in which the artist writes: ‘Many thanks for your letter and cheque £10. I am very glad Mrs Wallace likes the picture Going to Work and take the liberty of asking you to please accept The Manufacturing Town as a souvenir of the Civic Week. I can assure you that it will always be with great pleasure that I shall think of that Saturday morning.’

The latter painting was sold by the Wallace family – with Lowry’s blessing, as he understood that a new generation of the family needed help getting set up – and is now in the collection of the Science Museum in London. Going to the Mill was kept – recently being on long term loan to Pallant House Gallery, Chichester, and only comes to market now as a further generation finds themselves in need of a ‘leg up.’

Going to the Mill is the epitome of a 1920s Lowry, when he truly becomes a unique voice. In the overall smoky, sooty quality of the sky and buildings – it will be a few years yet before Lowry begins to stage his visions of the city against isolating backgrounds of plain flake-white – we see the influence of his teacher, Alphonse Valette, who had been drawn to Manchester precisely for its grit and the Romantic quality of its dark streets and thick polluted skies, the poetic fallacy of heavy-set architecture shrouded in smog, from which individual stories emerged, lamp-lit for moments, before being swallowed up by the gloom. Yet Lowry holds our attention to these individual lives much longer (and this is eventually the function of those white backdrops, to separate individuals from the mass and to hold them in time). Looking at Going to the Mill, initially all we see is a crowd, drawn inextricably – like water pouring towards a drain – to the gate of the mill on the left. But Lowry invites us to spend time looking, and slowly the painting reveals the men walking away from the mill, the woman standing alone looking out at us, drawing the viewer into the lives of others, or the man carrying what seems like a large portfolio, who could be an avatar of Lowry himself. As such, the crowd is broken down into individuals, each with a story – a story that Lowry himself manages to capture with a flick of the brush, a weighting of the paint, a bend of the knee or turn of the shoulder. Going to the Mill shows us that he is no naif painter of ‘matchstick men and matchstick cats and dogs’ as the old pop song goes – this is an artist of true dexterity who is making a deliberate formal choice, abstracting the figure, in order to express a concept, the sense of a life lived in even the smallest, most incidental figure. His works are as composed and deliberate as Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte but imbued with an intensity of feeling more easily found in Van Gogh’s early paintings of Dutch peasants. These comparisons are not over-blown, not least as Lowry, in the early 30s, was one of the very few British artists exhibiting in the Salon in Paris and gaining recognition for the precision and intensity of his vision. And it is important to note that it was T. J. Clark, the great art historian of French painting of the late 19th and early 20th century, who curated Lowry’s 2014 Tate retrospective and presented Lowry deliberately as another of the great ‘painters of modern life’.

Lowry’s paintings are never simple renditions of what he saw on the streets of his beloved city (or, more accurately, cities – Salford and Manchester). Works such as Going to the Mill are theatrical in their conception, which is why the ‘backdrop’ of the mill at Pendlebury repeats itself, often in altered configurations, throughout his works – such as the slightly later A Town Square, formerly in the Midland Bank collection, which sold at Sotheby’s in 2024. The city becomes a stage for an exploration of loneliness, isolation, loss, hope, although in Lowry’s hands the buildings themselves function as actors – figuring birth, marriage, death and the tyranny of mill-time, before, in later works, they are enveloped in an all-consuming white of Beckettian structure. Lowry was an inveterate theatre-goer who – intriguingly, instructively – cited both the 1920s ‘kitchen sink’ drama Hindle Wakes and Luigi Pirandello’s absurdist masterpiece Six Characters in Search of an Author as highly influential on his work. The breadth between these two plays indicates the breadth of Lowry’s conceptual framework for his apparently ‘simple’ painting. This conceptual reach, centred on the urban experience, is – as T. J. Clark argues so persuasively - what makes Lowry so relevant today, in our world of megalopolises, many of them growing at the same break-neck speed as Victorian Manchester once did.