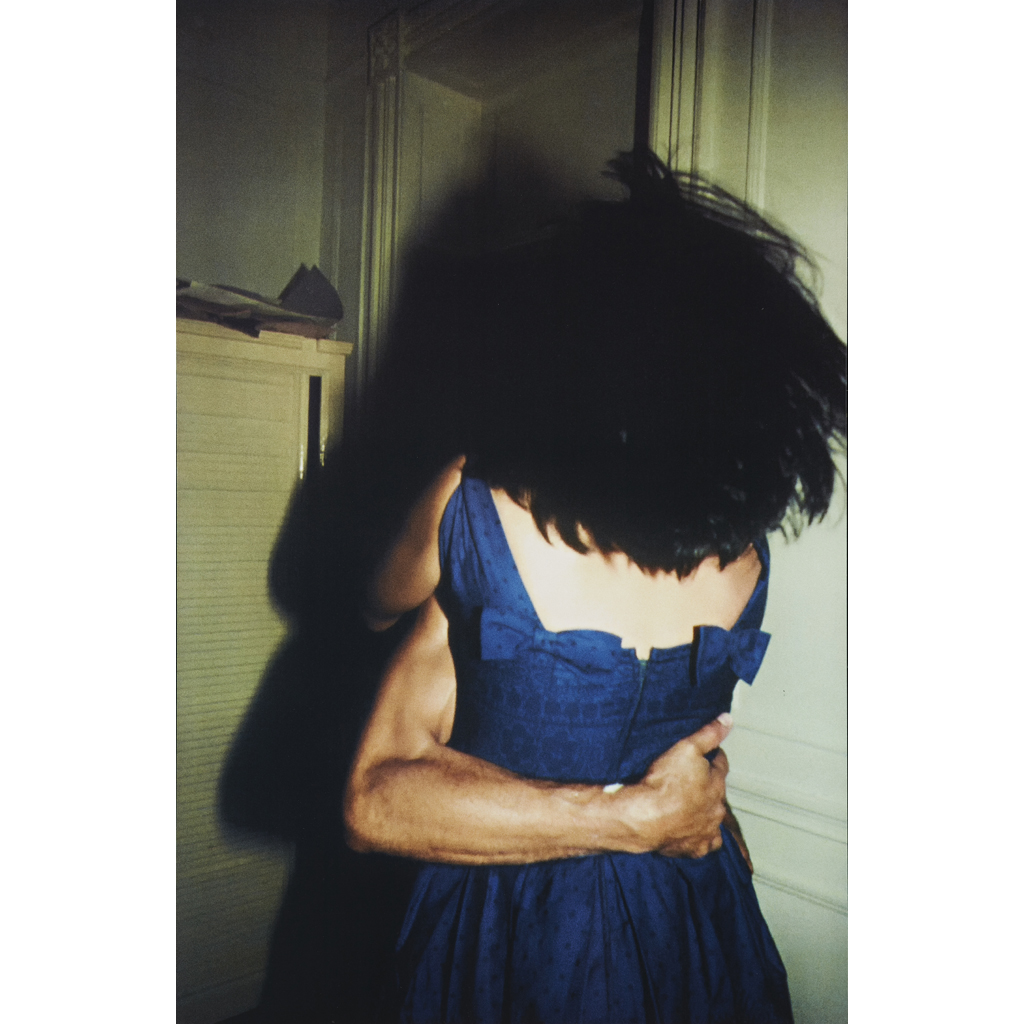

NAN GOLDIN (AMERICAN B.1953)

THE HUG

£3,750

Modern British & Contemporary Art

Auction: 16 August 2018 at 12:00 BST

Description

C-print mounted on Sintra foam-board, artist's proof, signed and inscribed verso 'Sometime it hurts, sometimes it don't, you know N.'

Dimensions

39cm x 59.5cm (15.25in x 23.5in)

Footnote

Note:

Nan Goldin

'For me taking a picture is a way of touching somebody-it's a caress. I'm looking with a warm eye, not a cold eye. I'm not analysing what's going on-I get inspired to take a picture by the beauty and vulnerability of my friends.'

It is difficult to imagine in 2018, when everyone is an amateur photographer, a smart phone with built-in camera feels like an extension of self to most people and Instagram, the image-based social media platform for sharing 'snapshots' of your life is rapidly gaining popularity, how radical Nan Goldin's work was when she first unleashed her vision and aesthetic on the art world in 1973.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is the over-arching name for a body of work created by Goldin depicting her social circle and their life through the 1970s and 80s. Created over many years, it was originally presented by the artist as a slideshow set to music, totalling approx. 700 images in a period of around 45 minutes, before being published as a book in 1986. It has more recently been re-presented in its original slideshow format in a selection of art institutions. Both artworks offered in this auction, The Hug and Skinhead with Child, London, 1978 are from this body of photography.

With her captivating and immediate 'snapshot' style, Nan Goldin's photography creates an intersection of autobiographical detail and documentary storytelling, as she honestly captures her friends as they live their lives, creating a body of work that is at once radical, intimate, personal, joyful and moving. Her circle of friends, subsumed as they are in the New York counter-culture of the 1970s and 80s, are shown in their beds, kitchens and living rooms, embracing, dancing, kissing, dressing, undressing and shooting up with a casual immediacy and frankness that can be disconcerting for the viewer.

Yet Goldin was not a casual observer of this lifestyle, and was instead a close friend of all the people depicted, living with them and participating in this hedonistic lifestyle. She called these close friends her family, describing them as 'bonded not by blood, but by a similar morality, the need to live fully and for the moment.' She said of her artistic intentions, 'I know how to make someone look beautiful. And I'll never photograph anyone I don't know. You have to know the person to really be able to photograph them. But I never show pictures of my friends if they don't want me to. My drawers are full of great photographs that I won't show because the person asked me not to.' The sense of the work as confessional and uncompromising, making private acts, spaces and moments public is only strengthened by the artist's commitment to self-portraits. She is as unflinching an observer of herself as of others, and her gaze is always one of love and connection, rather than interrogation or judgement. By her own admission, her photography is 'the diary I let people read.'

Goldin's style and approach always stemmed from her life and circumstances, from capturing those closest to her, to working with artificial light as that was how she saw and experienced her life at that time, living almost nocturnally in central New York, and utilising slides and getting her prints developed in the chemists as she had no access to a darkroom. In The Hug, we get a real sense of Goldin's approach, the camera and photographer as observer of an intimate moment, of human affection and connection, yet also with a potentially darker edge of vulnerability and power; it only takes a single male arm to completely encircle the woman's body. The complexity of human connection and our way of relating to each other is reinforced in the artist's handwritten inscription, 'sometimes it hurts, sometimes it doesn't, you know.' While Skinhead and Child, London, 1978, demonstrates Goldin's keen visual eye, capturing this odd juxtaposition of figures with its surprising compositional balance, and nods to the luck and circumstance inherent in the medium of photography, of hundreds of photographs taken, this is one of the images that delivers, the light and patterns giving an strikingly eerie and ghostly effect.

In 2018, Goldin's striking photographs continue to attract different meanings and foster new connections, as we read and experience them in relation to current events and attitudes. Goldin herself has said, 'I always thought if I photographed anyone or anything enough, I would never lose the person, I would never lose the memory, I would never lose the place. But the pictures show me how much I've lost.' And we can feel that even more acutely now, as we realise that many of the subjects, the friends and adopted family of the artist, have not survived, they are a generation lost to drugs, AIDS and suicide and although they have been captured in these specific moments, we do not know the entirety of their complicated story.