Lot 28

AN IMPORTANT MOSUL SILVER-INLAID BRASS CANDLESTICK

MOSUL, FIRST HALF OF 13TH CENTURY

Auction: 10 December 2025 from 14:00 GMT

Description

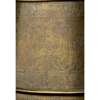

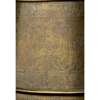

the body of conical form with a cylindrical neck and socket of conical form, the drip-pan a later Ottoman replacement, inlaid with cusped arcades on the body containing human figures and composite animals alternating with arabesques, the socket with similar decoration in miniature, the neck inlaid with T-fret decoration, kufic inscriptions above and below the decoration of the body, grafitto under one of the arcades

Dimensions

36.6cm high, 31.6cm diameter max.

Provenance

Discovered at a Bric et brac market in the South of France; subsequently sold through Marseille Encheres Provence, 17 June 2022.

Footnote

This remarkable candlestick belongs to a small group of such objects with large-scale figurative elements as their primary decoration and is one of only three where the figures are contained within the distinctive ogee arches seen here. That the original neck and socket still survive, even if the drip-pan has been replaced, makes this candlestick even rarer as only around half of the known examples retain these elements. Although much of the original inlay is no longer present, the candlestick is still in very good condition, and the extraordinary figural and arabesque decoration is clearly visible.

The distinctive tall, slightly tapered drum-shaped body with an overhanging shoulder and horizontal flanges above and below the main decorative field, as well as a socket which parallels the form of the body, first appears in Mosul in the first half of the 13th century. The earliest securely dated candlestick of this type, now in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston (inv. no. 57.148), is signed by Abu Bakr b. al-Hajji Jaldak and dated 622 AH/1225 CE [Rice, D.S., “The Oldest Dated ‘Mosul Candlestick” in The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 91, No. 561 (Dec., 1949), pp. 334, 336-341]. The Boston candlestick, and another in the Khalili Collection (inv. no. MTW 1252), are the only two known candlesticks other than the present example which feature the primary figural imagery set within cusped arches. The Khalili candlestick, which is missing its neck and socket, also carries kufic inscription bands above and below the images on the body which have not yet been deciphered. Although unsigned, it has been attributed to the ‘Mosul School’ of Ahmad al-Dhaki and his student Abu Bakr b. al-Hajji Jaldak [Makariou, S. (ed.), l’Orient de Saladin: l’art des ayyoubides, Éditions Gallimard, 2001, pp. 140-41 cat. 114]. Given the similarities between all three pieces there is good reason to believe that the present candlestick was also made in Mosul around 1225, possibly even in the same workshop as the others.

The imagery of the present candlestick is highly unusual, and while some of it is directly comparable to other Mosul metalwork other elements are apparently unique. Six of the arches contain figures. The first is a relatively straightforward enthronement scene, with a ruler seated cross-legged on a raised dais according to the classic medieval Islamic iconography. Below him are two composite animals, one a winged lion and the other with the same body but an eagle’s head. The next figural arch contains a heraldic brachycephalic eagle. Subsequent arches feature a standing, robed figure with hands crossed at their waist, a mounted hunter, two men wrestling, and a scene of relaxation under a tree. The non-figural arches as well as the spandrels are filled with dense, vertically-aligned arabesques.

Although the enthronement scene is commonly found in Mosul metalwork, its juxtaposition on this candlestick with a heraldic double-headed eagle suggests a deeper meaning. Bicephalic eagles were widely used as symbols of royalty in 13th century Anatolia, Iran, and the Jazira, where they appeared on architectural decorations, coinage, and portable objects. On occasion lions, which had similar connotations of princely power and protection, were included alongside these majestic birds, as on a textile in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. no. 2012.338) [Canby, S.R. et al, Court and Cosmos: The Great Age of the Seljuqs, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2016, pp. 236–38]. In this instance, however, the heads differ: one is an eagle, while the other has the distinctive flattened muzzle used for lions’ heads on Mosul metalwork. This eagle-lion hybrid is echoed across the candlestick, with such hybrids appearing in three other arches, most noticeably beneath the seated ruler. This unusual, and perhaps unique heraldic hybrid does not appear in 13th century coinage and may therefore represent an as-yet unidentified blazon. It is possible that such imagery could be a visual play on a name or title containing the words for these animals [Allan, J.W., Islamic Metalwork: the Nuhad Es-Said Collection, Sotheby Publications, 1982, p. 74]. The winged lions’ reappearance at various points on this candlestick – beneath the throne, accompanying a hunter, and watching a wrestling match – seem to point to their role as protectors and companions, perhaps to the prince in his roles as ruler, hunter, and fighter A small, winged lion can also be seen below the mounted hunter on the Khalili candlestick, suggesting that this may have been a common feature of this group [illustrated in Makariou, S. (ed.), op. cit., p. 200].

Other elements of the decoration find parallels within the corpus of metalwork from the Jazira and Syria. Although the mounted archer is commonly found on metalwork of the period, the composition her is unusual in that the horse is shown rearing with its head turned back in front of the rider. Although this may have been necessary to fit within the confines of the arch, it gives the scene a great dynamism. A basin in the Louvre in the name of the Ayyubid sultan al-Adil II (inv. no. OA 5991), which can be dated to 1238-40 and is signed by Ahmad al-Dhaki, features a hunting scene on the inside which shows horses represented in much the same way [Makariou, S. (ed.), Les arts de l’Islam au musée du Louvre, Louvre Éditions/Hazan, 2012, illus. p. 177]. Similarly, the wrestlers relate closely to those on both the exterior of the al-Adil basin and a tray in the name of Badr al-Din Lu’lu’, the ruler of Mosul, in the Museum Fünf Kontinente, Munich (inv. no. 26-N-118) [Rice, D.S., “Inlaid Brasses from the Workshop of Aḥmad al-Dhaki al-Mawsili” in Ars Orientalis, Vol. 2 (1957), pp. 283-326, pls. 8a,e and 9f,i]. A further connection to Mosul and the workshop of Ahmad al-Dhaki can be seen in the arch with figures beneath a tree. The individual on the right holds a bottle, while the kneeling figure on the left holds a tube – possibly a flute, or a pellet-gun for shooting birds. Close comparison can be made between this and the scenes of the good life on a ewer in the Cleveland Museum of Art (inv. no. 1956.11), many of which show drinkers and their companions resting below a single, central tree [Rice, ibid., pls. 4-5]. The standing figure with crossed hands most closely resembles the Christian figures on a pyxis in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (inv. no. 1971.39a, b), who have similarly long bodies and are also shown standing in cusped arches. The figure shown on the present candlestick does not appear to correspond to the iconography of a specific saint, but given the regular appearance of such imagery on metalwork from the Jazira and Syria some cross-pollination of imagery is highly plausible, even if the patron or craftsman was not aware of its exact significance [Canby, S.R. et al, op. cit., pp. 265–67].

A further point of interest here is the appearance of a graffito beneath the eagle blazon. Engraved in a cursive style typically found on Zangid and Ayyubid metalwork, it gives the name and title of a later owner: al-Faris Aqtaya amir majlis (‘al-Faris Aqtaya, guardian of the [Sultan’s] seat’). Intriguingly, there are two known historical figures with this name from the end of Ayyubid rule and the beginning of the Mamluk period. The first is Faris al-Din Aqtay al-Jamdar, who took part in the murder of al-Mu’azzam Turanshah, the last Ayyubid sultan of Egypt, and was subsequently executed by the Mamluk sultan Aybak in 1254. The second Faris al-Din Aqtay was appointed as atabeg (regent) for Aybak’s eldest son al-Mansur Ali, and became known as al-Musta’rab. Earlier in his career, Faris al-Din Aqtay al-Musta’rab had served Badr al-din Lu’lu’ in Mosul, which provides a possible link to the present candlestick.

Found in a bric-a-brac market in the south of France and subsequently recognised for its exceptional importance, this candlestick is a rare and fine example of Mosul metalwork from the first half of the 13th century. Not only does it link to key pieces made by important Mosul metalworkers, but it carries vivid and varied iconography as well as a fascinating historical record in its graffito.