Lot 43

AN EXTREMELY RARE IZNIK POTTERY TILE FROM THE CINILI HAMAM

OTTOMAN TURKEY, CIRCA 1540

Auction: 11 June 2025 from 10:00 BST

Description

of hexagonal form, underglaze, the main field decorated in white against a dark blue background, with details picked out in turquoise, the primary element of the design is an asymmetrical prunus tree in blossom, growing from a bunch of fleshy saz leaves at the base, from this base also sprout two other stems in the saz style, the right one with a large rosette as well as buds and leaves, and the left stem ending in a distinctive three-petalled tulip decorated with dark blue dots and turquoise teardrop shapes, at the top right is a Chinese-inspired cloud motif, and the borders are of turquoise with a repeat pattern of rosettes in two different sizes

Dimensions

28.3cm diameter max.

Provenance

Baron Leon van der Elst (Belgian, 1865-1933).

Count Frederick van der Steen de Jehay (Belgian, 1858-1916).

Henriette de Jourda de Vaux (Belgian, 1865-1946).

Marie-Noelle Kelly (Belgian, 1901-1999); thence by descent.

THREE IZNIK TILES WITH NOBLE BELGIAN PROVENANCE (LOTS 43-45)

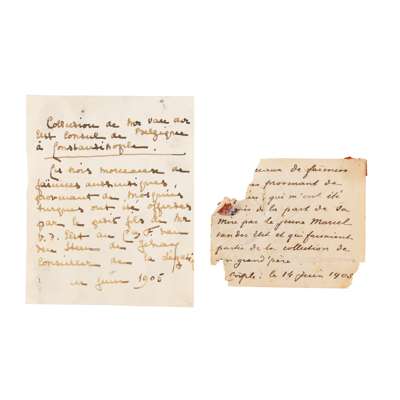

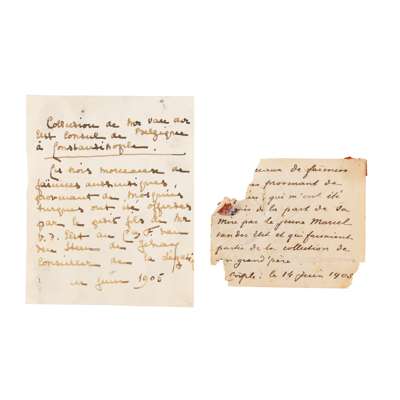

Each of the following three Iznik tiles (lots 43-45) are accompanied by handwritten notes dated to 1905. Whilst two of the notes have been detached from the tiles (see fig. 1a and 1b), they still have remains of the seal wax that was used to attach them. Lot 45, however, still has its note securely attached on the reverse (see fig. 2).

The note reads in French:

‘3 morceaux de faïence, provenant de mosquees qui m’ont ete données de la part de sa mere par le jeune Marcel van der Elst et qui proviennent de la collection de son grandpere. Conple. 14 juin 1905’

Which translates as:

‘Three pieces of pottery from mosques that were given to me by the mother of the young Marcel van der Elst, and that came from the collection of his grandfather. Constantinople 14 June 1905.’

Two of the notes are written in the hand of Count Frederick van der Steen de Jehay (1858-1916), the recipient of the Iznik tiles, who served as a distinguished politician and diplomat. Most notably, he was posted as special envoy to Istanbul from 1897-1905. The end of his appointment coincides with the year these tiles came into his possession, suggesting that they may have been given to him to mark the end of his tenure.

After his tenure in Istanbul, he was made Chief of Cabinet of the Belgian Ministery of Foreign Affairs. His wife, Henriette (1873-1957) was lady-in-waiting to Queen Elisabeth, wife of King Albert I of Belgium. Frederick and Henriette bore no children, and the tiles would have been inherited by her sister, Jeanne Snoy (1878-1955) who married Count Charles de Jourda de Vaux (1865-1946). It is through this line that the tiles were inherited by the late Sir Bernard Kelly’s wife, Marie-Noelle Kelly, niece of Jeanne Snoy, and have remained in the family since.

The grandfather of Marcel van der Elst is named as M. v. d Elst within a note written in a different hand (see fig. 1a). The name is likely to refer to Leon Baron van der Elst (1865-1933), a highly distinguished diplomat, negotiator, and was most notable for being the foreign affairs advisor to King Leopold II of Belgium from 1906 to 1918. In an historical biographical account, (see www.ars-moriendi.be), Baron van der Elst put Count ven der Steen de Jehay forward as chief ‘ad interim’ of the King’s cabinet from 1916 up until his death, highlighting the esteem the Baron held for the Count.

Although there are no further provenance details for the other two tiles, the prior history of the piece from the Çinili Hamam, lot 43, is known. An anonymous document addressed to Sultan Abdülhamid II states that a French antiques dealer, Ludovic Lupti, had stripped the hamam of its tiles around 1874 and subsequently taken them to France, paying pennies for each of them. From Paris he sold them to museums and collections across the continent for the princely sum of 24 francs each. This appears to have been the sole point of dispersal for all the tiles from this group, which can now be found in major collections in France, the UK, and Türkiye (see Özbay and Şengozer, Barbarossa’s Cinili Hamam: A Masterpiece by Sinan, 2023, pp. 52, 266).

Footnote

This tile is one of only three complete tiles bearing this pattern. The example in the Victoria & Albert Museum was made by cutting two damaged tiles and fitting the remaining parts together (see Atasoy and Raby, Iznik: The pottery of Ottoman Turkey, 1989, fig. 501). The third of these tiles is in the Ömer Koç Collection, Istanbul (see H. Bilgi 2015, no.15). Although the overall design of each is the same, suggesting the use of stencils, there are subtle alterations in details of colour and patterning between the three.

During the conservation of the Çinili Hamas which took place from 2010-23, fragments of tiles were found under and above the wall plaster, including several pieces of the same design as this tile (see Özbay and Şengozer, Barbarossa’s Cinili Hamam: A Masterpiece by Sinan, 2023, figs. 4.6e and 4.7 pattern 20). Exactly where this tile design was placed within the hamam is unclear, it is certain that both the men’s and women’s sections were decorated in this fashion, and hexagonal tiles appear to have been used side-by-side to create uninterrupted walls of a single design (opp, cit, pp. 192-7).

The basic design of the tile was clearly popular among the potters of Iznik and their clients. With a pattern spread over two tiles rather than one and with mossy green added to the palette, a contemporary tile panel in the David Collection employs the same elegant prunus along with the non-natural serrated leaves and tulips at the base, and both may have been inspired by the arts of the book (see Atasoy and Raby 1989, figs. 229-30, pp. 134-5). A blue-ground dish in the British Museum, made half a century later, uses a slightly simplified version of the same design (see J. Carswell, 1988, fig. 56 pp. 80-1).

The Çinili Hamam’s patron was none other than the great kapudan-i derya (Admiral) Hayreddin Pasha, better known in the West as Barbarossa. He was one of the most important characters of the reign of Süleyman the Magnificent, leading Ottoman naval forces across the Mediterranean from around 1510 until his death in 1546. That his hamam was constructed in the prestigious Zeyrek district of Istanbul was a testament to his importance, with the endowment deed of 1534 stating that the Sultan himself had reserved access to the nearby aqueduct’s water for the Hamam’s use (see opp. cit, pp. 78-9). As a key figure at the Ottoman court, Barbarossa was given access to both Sinan, the greatest architect of the time, as well as the Nakkaşhane (imperial painters’ workshop) which provided designs for the tiles. The baths were adjacent to the mansions of palace dignitaries as well as easily accessible from nearby main roads, making it an easy source of money to be provided to Barbarossa’s charitable foundations elsewhere in the city (ibid, pp. 181-4). Sinan himself was a pioneer in including tiles within the overall architectural scheme of buildings, as seen in the Çinili Hamam, and may even have been in charge of the Iznik ceramic industry in this period [Necipoğlu 1990, pp. 154-5].

Originally named after its patron or his titles as Admiral, the name by which the hamam is now known derives from the extensive tilework (‘Çinili’ means ‘tiled’), which distinguished it from other baths of the period which lacked extensive tile decoration. Such was the impression made by the tiles that one of the leading Ottoman poets of the day praised them on the occasion of the Hamam’s opening, suggesting that they had overcome even the ‘beautiful ones of China’. Although it was considered one of the preeminent baths of Istanbul during the 16th and 17th century, the Çinili Hamam was damaged by fires during the 18th century and finally destroyed by fire in 1833, passing through multiple hands thereafter (see opp. cit, 2023, pp. 82-91). After an extensive process of restoration, the hamam has now reopened, along with a small museum including both archaeological finds and the tile fragments found under the plaster. In its new state, it truly reflects the sentiment of the poetry found on some of the surviving tiles:

“The area of the bath is like Paradise/Although its foundations are made of clay and bricks” (see opp. cit, p. 43].