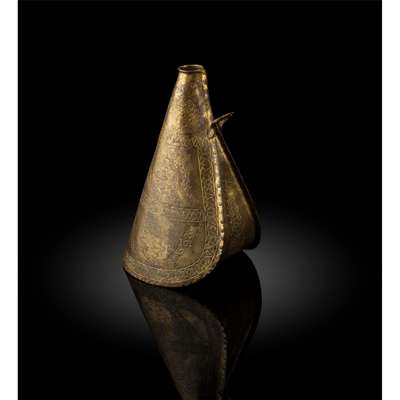

Lot 42

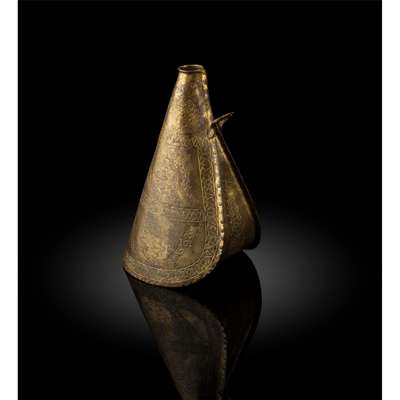

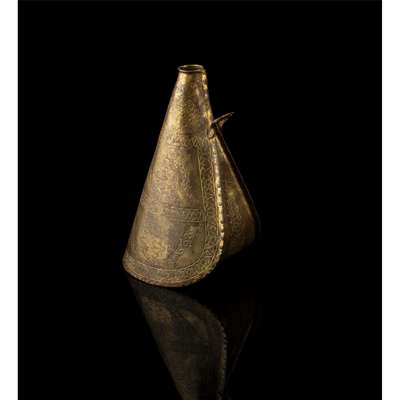

A RARE OTTOMAN GILT-COPPER (TOMBAK) PILGRIM FLASK (MATARA)

TURKEY, 17th CENTURY

Auction: Islamic Art | Lots 1 to 66 | 12 June at 10am

Description

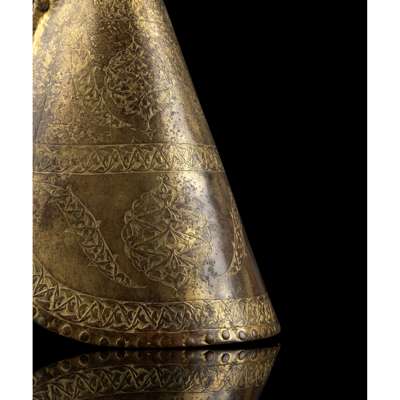

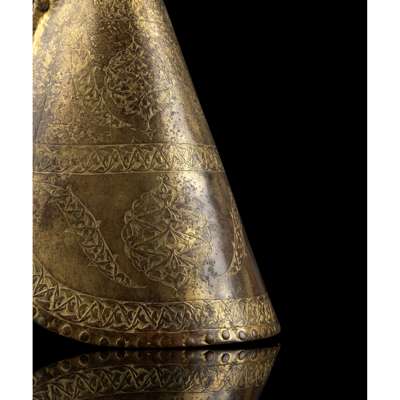

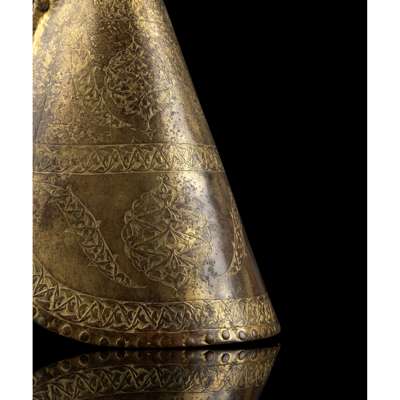

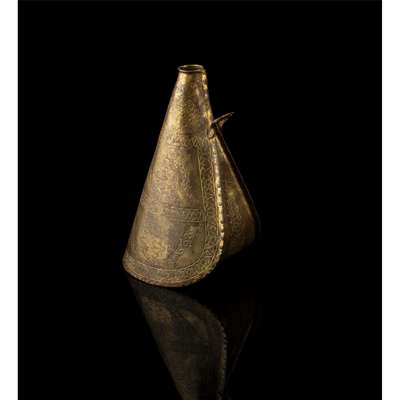

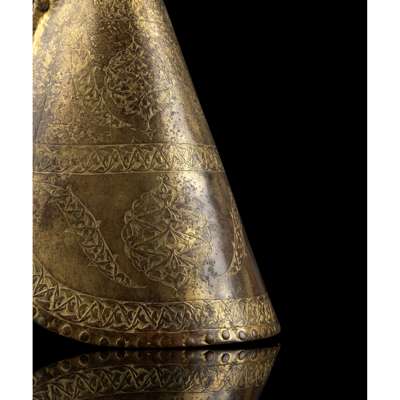

of slender pyramid form, made of two sheets of beaten gilded copper, one sheet wrapped like a robe and soldered at the collar with a circular narrow spout terminal, with a seam of rivets and a loop handle, the other sheet of metal soldered to the seams of the main sheet, the front engraved decoration divided into three wide bands containing large cusped medallions and palmettes filled with entwined split palmettes, continuous entwined split palmettes within the dividing bands

Dimensions

27cm (10 ¾in) high; 15.5cm (6 ¼in) max. width

Footnote

Note:

This is a rare and very fine example of an Ottoman matara or flask, a form drawn from the very humblest of materials but one which is associated with the power and piety of the Ottoman Empire at its peak. The present piece is formed from two sheets of metal, the larger folded around and joined at the back of the flask with a series of rivets. The material used is gilt-copper, referred to in Turkish as tombak; this term may be derived from the Malay tambaga (‘copper’), this metal being used in the alloy which forms the body. This surface would then be mercury-gilded, creating a luxurious effect often visually indistinguishable from pure gold (İ. Gündağ Kayaoğlu, Tombak, Istanbul: 1992, p. 2). The dating of the present piece is suggested through comparison with the palmettes on a parcel gilt silver incense burner in the Türk ve İslam Eserleri Müzesi, which carries the date 1033 AH/1624-5 CE (Yanni Petsopoulos (ed.), Tulips, Arabesques & Turbans: Decorative Arts from the Ottoman Empire, New York: 1982, p. 48 and fig. 53).

The rivets on this piece point towards the prototype of this form, referencing the heavy stitching used on contemporary leather mataras, including one of near-identical form now in the Sadberk Hanım Museum [Hülya Bilgi, Reunited after Centuries: Works of Art Returned to Turkey by the Sadberk Hanım Museum, Istanbul: 2005, no. 48]. Another flask in the Metropolitan Museum of Art also displays its debt to leather through both its form and decoration. Metal examples such as these would have been used as emblems of rank among the elite (Stuart Carey Welch, The Islamic World Vol. 11, New York: 1987, p. 125]. In the Tarih-i Sultan Süleyman, completed in 1579-80, the matara is shown as part of the Sultan’s personal regalia alongside his sword [Esin Atıl, The Age of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, Washington, DC: 1987, p. 94).

More than mere receptacles for water, mataras were an essential part of Ottoman imperial finery, and alongside the appliqué leather example sent as a diplomatic gift from Murad III to the Habsburg Rudolph II, now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna (C.28), there are examples in even more rarefied materials including gem-encrusted solid gold and rock crystal (Esin Atıl, The Age of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent, Washington, DC: 1987, pp. 123-5, 128-30). A later leather matara in the Khalili Collection (MXD 366), of the same shape as the present example, appears to have been used to hold water from the holy well of Zamzam in Mecca. A matara such as the present example can be seen as the nexus of faith and rule under the Ottomans, stretching between the imperial capital in Istanbul as far as the holy city of Mecca in the distant Hijaz.