Lot 493

RARE AND IMPORTANT FRENCH GOTHIC IVORY COMPOSITE CASKET Y

CIRCA 1330

Auction: Day Two: 20 May 2021 | From 11:00

Description

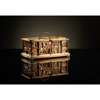

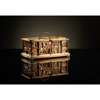

the panels intricately carved in bas-relief to include scenes from the Medieval tales Queste del Saint Graal and Tristan & Isolde, with later brass brackets, straps and handle [n1]

Dimensions

25cm wide, 11cm high, 13cm deep

Provenance

Provenance: Property from Tornaveen House, Aberdeenshire

Footnote

Currently only eight other complete secular ivory coffrets like the present one are known. These so-called composite caskets are mostly in important museum collections around the world.[1] With all panels intricately carved in bas-relief, the high quality of the workmanship is immediately visible, while a closer look reveals the richness of the motifs. It gives us a beautiful insight into the medieval fascination with the concept of courtly love.

The present example likely originated in a workshop in Paris around 1330, due to the similarities with the existing ones. The exact meaning behind the iconological programs of these caskets has long been a subject for discussion between scholars.

One thing the panels on all these caskets have in common is the link to medieval courtly literature, tales of love usually between knights and noble ladies emphasising nobility and chivalry, popular in Europe since around the time of the First Crusade in 1099. On this coffret, the two main tales the panels relate to are most likely Tristan and Isolde, and the Queste del saint grail. [2]

The two panels on the right side probably refer to the famous medieval romance, Tristan and Isolde. This tale, based on a Celtic legend, centres around the young knight Tristan, who travels to Ireland to ask for the hand of princess Isolde on behalf of his uncle King Mark of Cornwall. After slaying a dragon there, the princess agrees to marry King Mark. On the journey back Tristan and Isolde drink the love potion prepared by the queen for her daughter and King Mark and fall for each other. The main part of the romance is focussed on King Mark trying to prove their secret love affair and punishing them.

Although this legend has been retold many times, one of the most popular ones is the version by Béroul, a Norman or Breton poet of the 12th century. According to his account, King Mark asks King Arthur to try his wife Isolde at court for her unfaithfulness. To have Isolde exonerated from the charges, she and Tristan concoct a clever ruse. Tristan disguises himself convincingly as a poor leper, begging for alms on the banks of the river Malpas. When the royal party arrives, he carries her across the river, so Isolde can truthfully swear in front of the court that “no man ever came between my thighs except the leper who carried me on his back across the ford and my husband, King Mark”. This oath was seemingly so convincing, that everyone hearing it applauded it, and King Arthur made Mark promise to never slander her again.

The front left panel shows Tristan carrying Isolde across the river, her headdress clearly indicating she is a married woman. After Isolde is safe, Tristan dresses up as the Black Knight and joins the jousting, a scene represented on the left end panel of the casket.

The carvings on the front right and right end panel allude to another preeminent story, the Queste del saint grail, the story of the fabled Holy Grail, part of the Arthurian Legend. It begins at King Arthur’s court with a gathering of the well-known Knights of the Round Table. Just before dinner a sword in a stone appears miraculously floating in the river below the castle. Lancelot’s claims that whoever tries to remove the weapon will be gravely wounded does not deter his companions eager for adventure. Only the recently arrived Galahad can withdraw the sword, which he uses to achieve the quest for the grail.

The carving next to the lock on the right of a man presenting his arm with severed hand to a king and queen probably relates to this, he having failed to retrieve the sword and receiving this grisly injury in trying so. The sword over the altar on the right end panel possibly refers to the divine and miraculous nature of the weapon Galahad obtained. The scene on the right end could either show the appearance of the grail just after Arthur, Galahad, and the knights of the Round Table sit down to eat, or when Galahad and his companions finally encounter the grail at the end of the story, or a conflation of the two. That the figure in the middle of the right end panel lacks a crown suggests that he is Galahad and not Arthur. The lions shown on the lid support this identification, as the grail castle was guarded by lions and surrounded by water.

The wild men presented in intricate detail fighting to conquer a castle on the lid, and again defeated and in chains on the back panel, are a very popular motif in medieval imagery, ubiquitously represented in art of the highest quality from the early 14th century and continuing well into the sixteenth century[3]. Wild men represented the opposite of accepted standards of society, subliminally implying chaos, insanity and ungodliness. Especially in the 14th century the wild men seem to take on an erotic role, seen storming the Castle of Love in several artworks, one of the most common allegorical scenes in which the winning of a lady’s heart is depicted as the siege of a castle[4]. The carving on this coffret actually is reminiscent of the so-called Academy Casket (see image 1), now lost.[5]

Unusual on this panel is the wild man wearing a crown. There are some wild men wearing crowns in 15th century German tapestries (image 2), but we don’t have an explanation why the carver added one in this case.

The overall iconography of this casket seems to confirm the general notion that they were made as courting or wedding gifts for noble ladies, personalised to the commissioner’s preferences, as all the panels include notions of love and chivalry, to perhaps represent wishes for the future relationship especially important to the suitor. These very personal meanings have been lost to time, yet make this coffret extraordinarily intriguing.

Another element making this casket so significant is the impeccable provenance. We can trace it all the way back to the beginning of the 17th century, as it is mentioned in the family genealogy of the Baird family of Auchmedden[6] in relation to Thomas Baird[7]. According to this text, he became a friar of a monastery in Besançon, Burgundy, in 1615. Letters from his uncle Andrew, who was staying close by in France, to his father Gilbert mention him to be hard of learning and ‘incapable of any of the sciences’. His saving grace was said to being excellent at mechanics, having made ‘an oblong, small chest of ivory 10 inches long, 5 broad, and 4 high, delicately carved in bas-relief, with the chisel, upon the top and sides into figures of knight-errants, distrest [sic] damsels, and enchanted castles, taken from some of the old romances which were so much in vogue in that age’.

None of the letters later on in the genealogy indicate as to why the author thinks the casket was made by Thomas Baird, and not just sent over to his family as a gift. We don’t know if it was Thomas himself trying to make up for his shortcomings as a scholar by telling his family he was the talented maker, or if this is down to family lore evolving over the centuries. The casket would have already been nearly 300 years old at the time of Thomas’ acquisition.

A footnote in the genealogy places the casket in the editor W. N. Fraser’s possession in 1870, which gives us the firm link to the present-day vendors, who are descendants by marriage of the Baird family.

[1] Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 17.190.173, 1988, 16; British Museum, London, Dalton 386; Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 146.1866; Walters Museum, Baltimore, 71.264; Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham; Bargello, Florence, 123 c.; Cathedral Treasury, Krakow; Winnipeg Art Gallery

[2] Thanks to Paula Mae Carns for identifying the various iconography

[3] Timothy Husband, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gloria Gilmore-House

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980, p. 4

[4] Timothy Husband, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gloria Gilmore-House

Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1980, p. 73

[5] The location of all panels from this dismantled casket is unknown, apart from the back panel which is now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (2003.131.2). This casket is known from an eighteenth- century engraving (see Lévesque de Ravalière).

[6] Genealogical collections concerning the sir-name of Baird, and the families of Auchmedden, Newbyth, and Sauchton Hall in particular : with copies of old letters and papers worth preserving, and account of several transactions in this country during the last two centuries: Baird, William, 1700 or 1701-1777, edited by W. N. F. Fraser, London 1870, page 21

[7] The exact dates for Thomas Baird are unknown, however he is known to be the third son of Gilbert Baird (1551-1620), and he resided in France from at least 1609.

Note: Please be aware that this lot contains material which may be subject to import/export restrictions, especially outside the EU, due to CITES regulations. Please note it is the buyer's sole responsibility to obtain any relevant export or import licence. For more information visit http://www.defra.gov.uk/ahvla-en/imports-exports/cites/