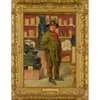

Lot 50

HENRY STACY MARKS (1829-1898)

‘A FISH OUT OF WATER’

Auction: Lots 1 to 336 | 16th October at 10am

Description

oil on canvas, signed and dated lower right H. STACY MARKS 1858, framed

Dimensions

35cm x 24cm (frame size 47.5cm x 36.5cm)

Provenance

Provenance: Christies, London Fine Victorian Pictures, Drawings and Watercolours, 9th June 1995, Lot 396

Footnote

Note: During the 18th century there was a growing sentiment that public institutions should be accessible to all. An increasing number had free admission and late opening hours to enable the working classes to visit, principles on which Henry Cole, the first director of what became the V & A, was particularly adamant. In conjunction with this movement however, were changes to the behaviours considered acceptable within the museum space. For example, whereas in the 17th and 18th centuries visitors were encouraged to touch exhibits, by the 19th century this was forbidden and seen as undignified. Victorian guidebooks presented museums as agents of decorum, teaching the crowds how to act within these cultural spaces to which they now had theoretically unlimited access.

Beginning his artistic career in the mid-19th century, Henry Stacy Marks’ work engaged with contemporary debate. In 1862, just three years after he painted this work, he was a founding member of the St John’s Clique. This small group of artists saw the Royal Academy’s continued promotion of academic art as archaic, and instead concentrated their efforts on genre painting. They believed art should be judged by the public rather than conforming to pre-existing ideas.

In ‘A Fish Out of Water’ Marks uses art to imitate reality, presenting a member of the working class in simple dress and mud-coated boots, his bemused expression further demonstrating his incongruity in the museum setting. The almost indistinct plaque to the bottom left instructs him how to behave; ‘VISITORS ARE PARTICULARLY REQUESTED NOT TO TOUCH ANY OF THE SCULPTURES’. The painting could be interpreted as a wealthy, upper-class artist mocking this ignorant and awestruck individual. Given Marks’ rebellion against traditional art and the Royal Academy however, it seems more likely that he is commenting on the chasm between expectation and reality. Victorian idealists thought museums capable of spreading good taste to the masses, but achieving this was a far more complex and less easily romanticised venture.