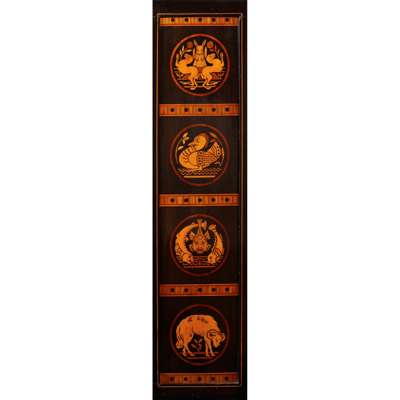

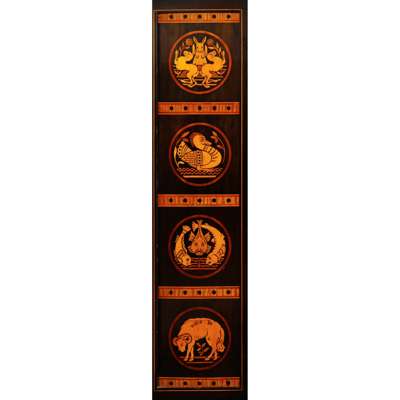

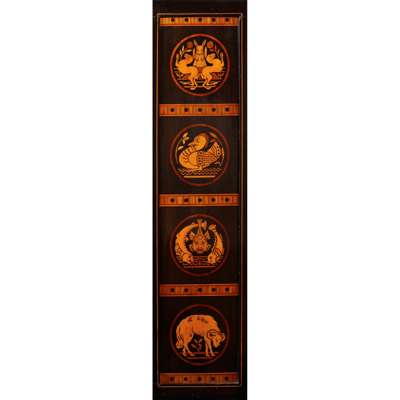

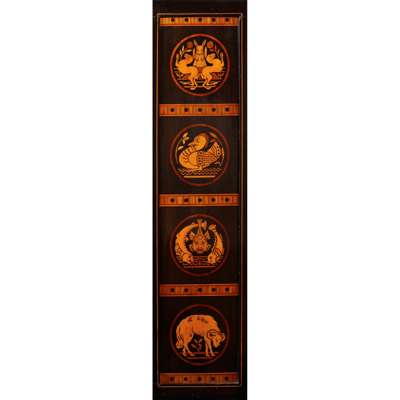

Lot 83

ATTRIBUTED TO CHRISTOPHER DRESSER OR JOHN MOYR SMITH, POSSIBLY FOR COX & SONS, LONDON

AESTHETIC MOVEMENT EBONISED AND INLAID CORNER CABINET, CIRCA 1875

Auction: Day One: 02 November 2020 | From 10:00

Description

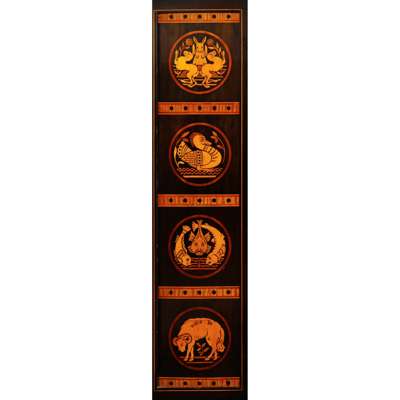

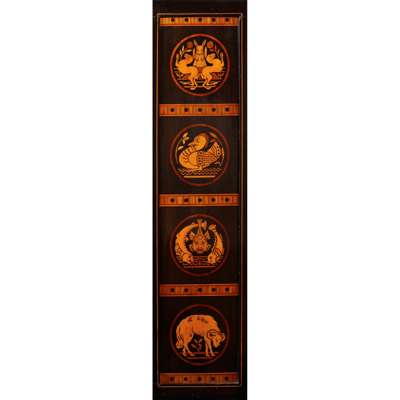

the galleried top with frieze inlaid with florets, the glazed door with lined and shelved interior enclosed by panelled sides, each inlaid with figurative allegorical roundels, the whole raised on a plinth base

Dimensions

68cm wide, 109.5cm high, 50.5cm deep

Footnote

Literature: Lyons, H. Christopher Dresser: The People's Designer, 1834-1904 (Woodbridge, 2004), p.19, 52 and 144; plates 12, 13, 51, 52, 260 and 260A

Durant, S. Christopher Dresser, Academy 1993, p.19-20

Whiteway, M. (ed.), Shock of the Old: Christopher Dresser's Design Revolution, New York, 2004,

Stapleton, A. John Moyr Smith 1839-1912: A Victorian Designer, Richard Dennis 2002, pp.11-15, plates 11 and 12

Cooper, J. Victorian & Edwardian Furniture & Interiors, Thames & Hudson 1998, pp.130-132

Woolley & Wallis, Salisbury, 20th Century Design, 14 October 2009, lot 549

Note: This fine cabinet, although of conventional form, has particular design characteristics which set it apart; its distinctive gallery and the fine marquetry panels inlaid to the sides. The design of two of the inlays appear to be adapted from colour plates published in Christopher Dresser’s Studies in Design of 1876 - the hares from plate VII; and the duck from bird designs in plates XLVI and VI. There are also strong similarities to an illustration in his Principles of Decorative Design of 1873 (the fish from figure 20); and bird and animal designs for Minton & Co. circa 1871. These designs were, like other output from the Christopher Dresser’s studio, often drawn up and, on occasion designed under Dresser’s supervision by an assistant. In the case of the first two examples this assistant is thought to be the Scottish-born designer John Moyr Smith.

The confusion surrounding the attribution of certain designs by Dresser is largely due to a lack of information but also that the stylistic similarities of many of his designs to those of his assistants is so striking. Some assistants were to leave Dresser’s offices and pursue careers of their own and although most believe that Moyr Smith worked for Dresser in his studio for a short period it may also be the case that he collaborated with him in the supply of designs to his projects on an ongoing basis. Whether he worked for Dresser directly or not by 1872 Moyr Smith was an independent designer supplying designs to a number of manufacturers including Cox & Sons in London. The firm of Cox & Sons, originally church furnishers, were involved in the art movements in the second half of the 19th century and commissioned furniture, metalwork, stained glass and ceramic designs from several leading designers, including Bruce Talbert and E.W. Godwin.

Cox & Sons also supplied stained glass to some of Christopher Dresser’s interior projects, but if Dresser used them in a wider sense is unclear. He was obliged to distance himself from their output because of the similarities of his designs to those of Moyr Smith. The attribution to Cox & Sons is strengthened by the fact that the firm is known to have used one of the designs used on this cabinet on a single-handled vase (Woolley & Wallis, October 2009, Lot 549).

Many of the firms who produced Dresser's textile and carpet designs believed in his abilities as a designer and were all based in the Halifax region. A number of them also commissioned Dresser to design the interiors of their homes. Of those only two domestic commissions survive and are in very poor condition, leaving only clues to the total composition of Dresser's interiors. In 1865 The Furniture Gazette published designs for the panels in dining room supplied by Dresser to J.W. Ward of Halifax, a textile maker who used Dresser’s designs. The panels represented fish, fowl, flesh, fruit, wine and beer.

The panels in the current lot, representing Game, Fowl, Fish and Mutton may also have been designed for a similar dining room scheme. The profuse, albeit restrained, marquetry inlay of this cabinet is somewhat at odds with Dresser’s more characteristically austere and pared-down aesthetic. He was, however, known to have been expedient and his ‘theoretical utterances’ did not always get in the way of the success of a busy studio where it was impossible to be entirely pure in intention. Many of Moyr Smith’s published designs of the 1870s were later ascribed to Dresser suggesting their origins in Dresser’s studio. Either way, until further information emerges, the attribution of many of these intriguing pieces remains unclear.