Lot 22

Klingenstierna, Samuel (1698-1765)

Autograph letter signed to James Stirling, with additional mathematical demonstrations

The Library of James Stirling, Mathematician

Auction: 23 October 2025 from 13:00 BST

Description

Letter dated ‘Holmiae’ [Stockholm], 19th September 1738, in Latin, addressed to ‘Clariss. Viro Jacobo Stirlingio’, 2 pages, seeking advice on apparatus for experiments in optics, and requesting books including Smith's ‘Systeme of Opticks’ and Maclaurin's ‘Systema Algebrae’, 23.5 x 18cm.

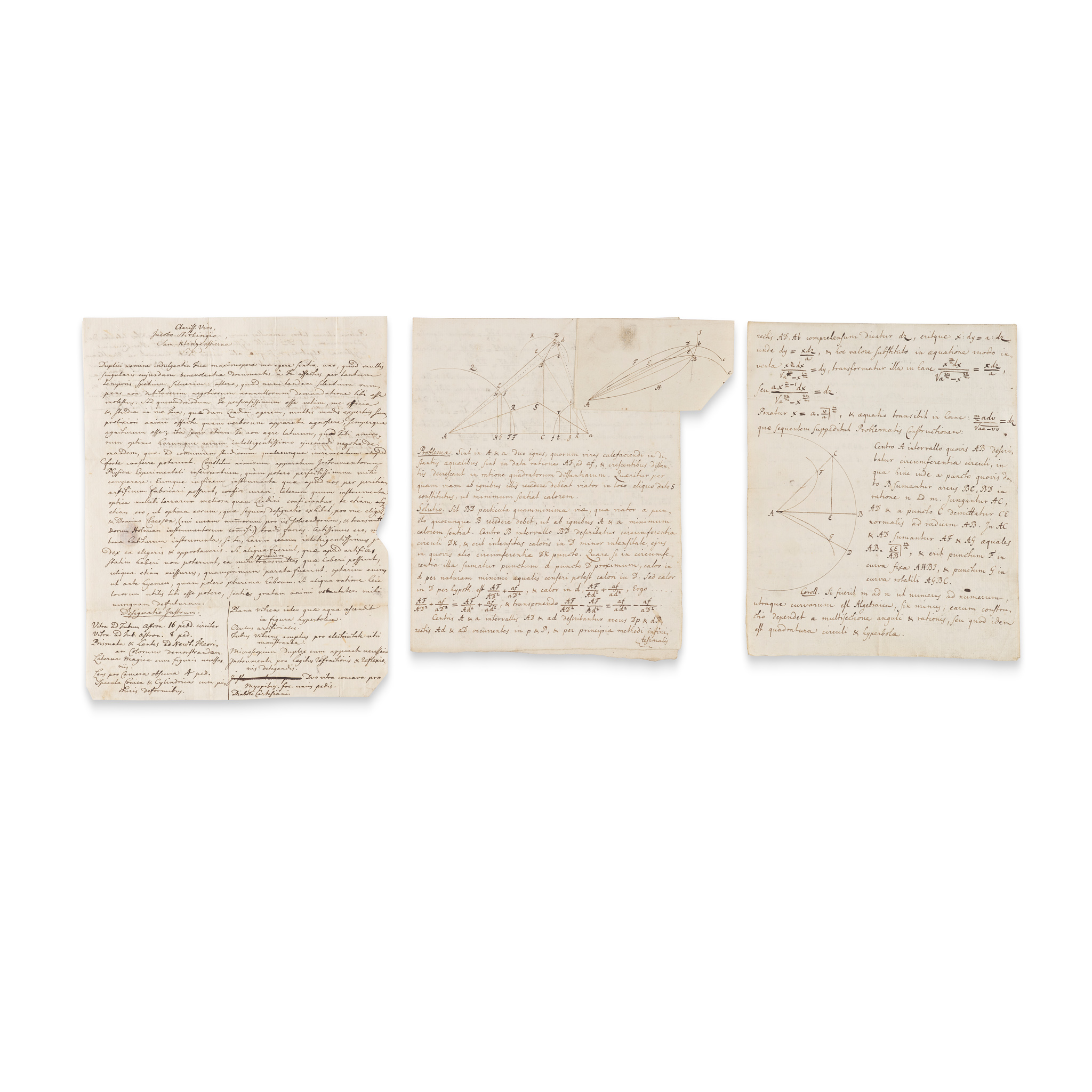

The mathematical demonstrations 5 pp. (on 3 sides of a bifolium and both sides of a single sheet), both unsigned but annotated ‘Klinginstern to Stirling’ in a later hand, with diagrams (one on a slip tipped to first leaf of bifolium), apparently containing at least 2 geometrical problems with solutions, approx. 21 x 16.4cm (3)

Footnote

Mathematician and physicist Samuel Klingenstierna was one of Sweden's leading proponents of Newtonianism in the early 18th century. From the 1720s he began to give lectures at Uppsala on Newton and Leibniz, becoming ‘the initiator of infinitesimal analysis in Sweden’ (Garding, Mathematics and Mathematicians: Mathematics in Sweden before 1950, 1998, p. 2). In 1727 he travelled to Marburg, meeting Leibniz's pupil Christian Wolff and writing a manuscript completing the proofs in Newton's treatise on real plane curves of the third degree, unintentionally duplicating James Stirling's work on the subject. In 1730 he visited London and was appointed fellow of the Royal Society, with Stirling receiving advance notice of his arrival via a letter of recommendation from Swiss mathematician Gabriel Cramer (see lot 21). The following year Klingenstierna became professor of geometry at Uppsala, later proceeding to the chair in physics. Perhaps his most important contribution came in 1755, when he ‘briefly and elegantly proved that Newton’s dispersion law [as described in Opticks] implied that a series of refractions had a dispersive effect when the emerging ray was parallel to the original ray … This meant that either the law was wrong or the prism-in-prism experiment as wrong' (Darrigol, A History of Optics, 2012, p. 119). The discovery was followed closely by the invention of the achromatic lens by English instrument-maker John Dollond, leading to a drawn-out priority dispute.

Published:

Charles Tweedie, James Stirling: A Sketch of his Life and Works along with his Scientific Correspondence, 1922, pp. 164-171.