Lot 17

Maclaurin, Colin (1698-1746)

Ten autograph letters signed to James Stirling

The Library of James Stirling, Mathematician

Auction: 23 October 2025 from 13:00 BST

Description

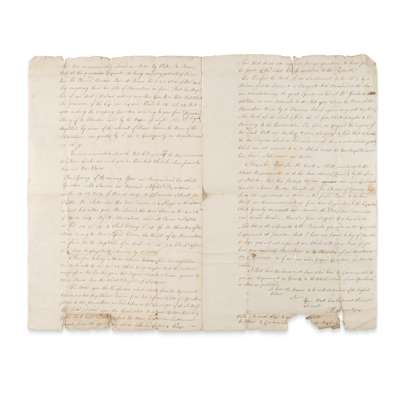

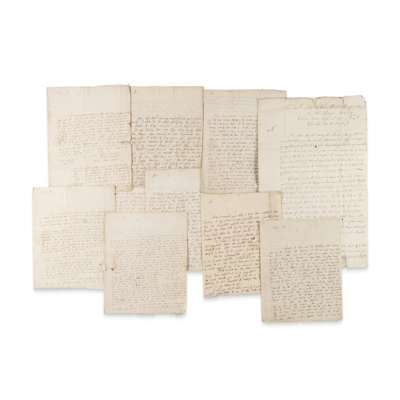

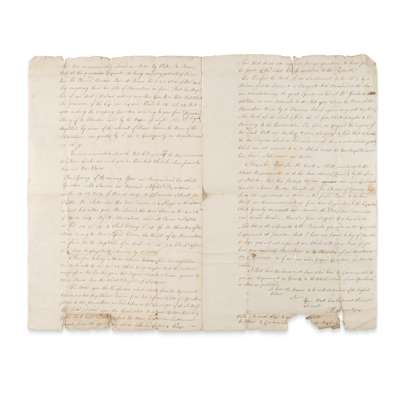

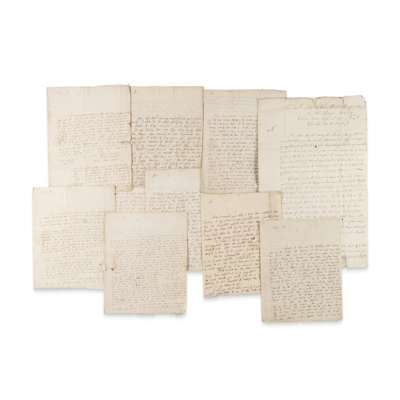

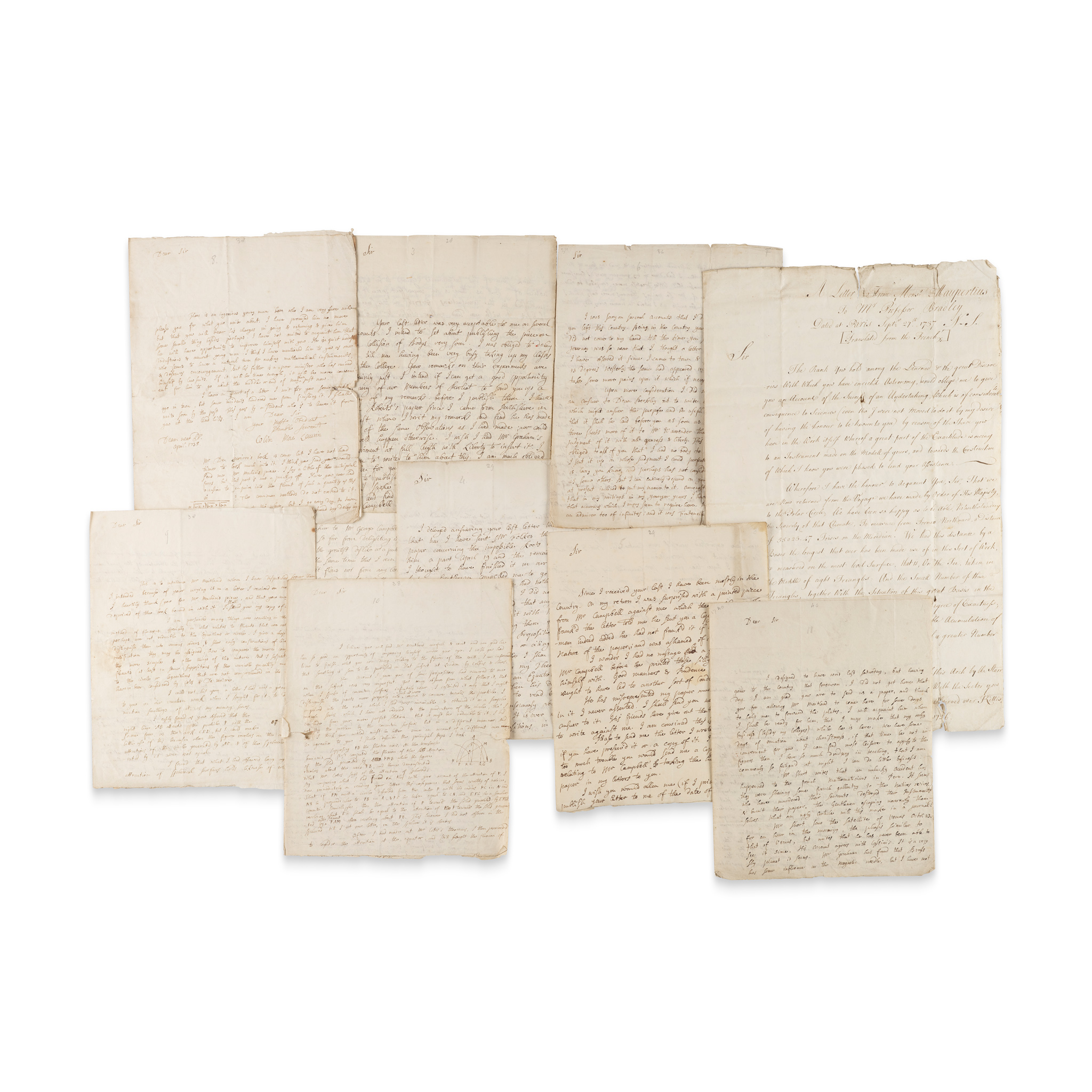

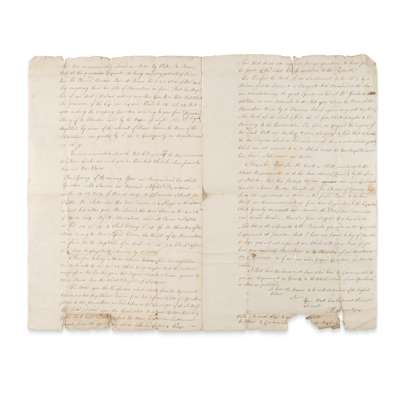

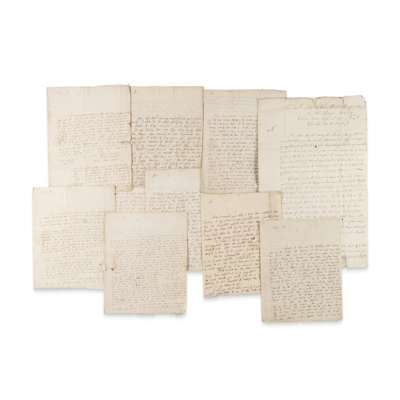

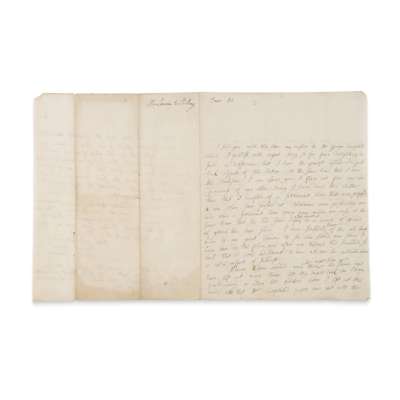

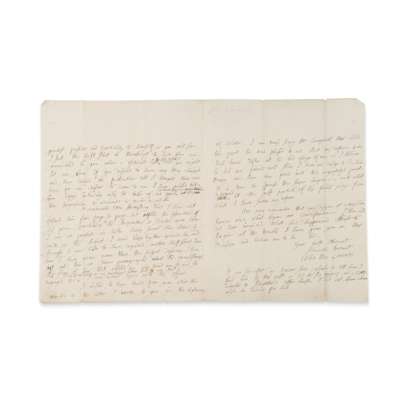

each a single bifolium, 4to, approx. 19 x 23cm or similar (except item 6: folio, 38 x 24cm), addressed to Stirling ‘at the Academy in Little Tower Street’, London, or at Leadhills, items 6, 7 and 10 annotated with mathematical calculations, likely by James Stirling (the annotations to 6 and 7 in pencil, those to 10 in ink).

1. Edinburgh, 7th December 1728, on his intention to published a piece on the collision of bodies ('I wish I had Mr Graham's Experiment at full length with Liberty to insert it'), his response to the nascent priority dispute with George Campbell (his ‘design of giving a Treatise of Algebra’, his ‘method of demonstrating that [i.e. Newton’s] rule by the Limits’, by which ‘too I demonstrate a Theorem in y[our?] book where a quantity is expressed by a series whose [coeffi]cients are first, second, third fluxions etc. I shall be vexed a little if he has taken this from me’), and other matters (’I expect to dispose of the six subscriptions I took for Mr De Moivre's book'), 3 pages, seal tear affecting a few letters, old staining;

2. Edinburgh, 1st May 1729, on the priority dispute with Campbell regarding impossible roots (‘I have sent Mr Folkes the remainder of my paper … I am satisfied that any person who will read this paper and compare it with Mr Campbell’s will do me justice … The proposition I sent you in my last letter is the foundation of all my Theorems about the impossible Roots)', 3 pages, loss to conjugate leaf affecting a few words;

3. Edinburgh, 6th November 1729, on the dispute with Campbell (‘I wonder I had no message by a good hand from Mr Campbell before he printed these silly reports … He has misrepresented my paper much and found things in it I never asserted’), 3 pages;

4. undated, probably 1729, on the dispute with Campbell (‘I send you with this letter my answer to Mr George Campbell which I publish with regret being so far from delighting in such a difference that I have the greatest dislike at a publick dispute of this Nature'), also mentioning a debt of six guineas to Abraham de Moivre, small closed tear to first leaf and seal tear to second with no loss of text, 3 pages;

5. Edinburgh, 16th November 1734, announcing his intention to write A Treatise of Fluxions (‘Upon more consideration I did not think it best to write an answer to Dean Berkeley but to write a treatise of fluxions which might answer the purpose and be useful to my scholars. I intend that it shall be laid before you as soon I shall send two or three sheets more of it to Mr Warrender that I may have your judgment of it with all openness and liberty … Robert Simpson is lazy you know and perhaps has not considered that subject so much as others. But I can entirely depend on your judgment. I am not at present inclined to put my name to it … I have some thoughts in order to make some of Mr De Moivre’s theorems more easy which I hope he will not take amiss’), and discussing other matters (his search for a copy of Machin’s book on the moon; ‘I observe in our news papers that Dr Halley has found the longitude', etc.), 3 pages, old ink-splashes and small seal tear to conjugate leaf;

6. 4th February 1737 [Old Style, i.e. 1738], comprising a secretarial copy of an English translation of a letter from Maupertuis to James Bradley, Paris 27th September 1737, announcing the return of the French expedition to Lapland, 1736-7, and describing in detail the findings of the expedition, 3 pages, with Maclaurin's autograph covering note to verso of conjugate leaf, with a postscript inviting Stirling to join a newly established ‘philosophical society’, i.e. the Philosophical Society of Edinburgh, a few small holes and marginal chips (causing loss of a few words in the postscript of Maupertuis's letter);

7. Dean near Edinburgh, April 1738, recommending ‘an ingenious young man here who I am very sure will please you' owing to his ‘natural turn for making mathematical instruments, with a postscript regarding the publication of De Moivre’s new book (presumably the second edition of The Doctrine of Chances) and mentioning centripetal forces, 1 page, small tear to edge of central fold partially obscuring one word;

8. 12th May, 1738, principally on fluxions (‘I am persuaded many things are wanting in the inverse methods of fluxions especially in what relates to fluents that are not reduced and perhaps are not reduced to the logarithms or circle. I give a chapter on these, distinguish them into various orders, and shew easy constructions of lines by whose rectification they may be assigned’), citing the work of Cotes and de Moivre, with 3 small mathematical diagrams, 3 pages, seal tear touching one word;

9. Dean, 20th May 1738, a detailed correction of an earlier mathematical demonstration, presumably that given in the previous letter (‘When I spoke of concentric surfaces infinitely near I restricted only that I might distinguish the parts more properly into such as were convex and concave towards the particle’), referring to Cotes's theorems, encouraging Stirling's work on the figure of the earth ('I wish you had time to finish what you are doing', with 2 small mathematical diagrams, 3 pages, small tears affecting a few words;

10. 6th December 1740, discusses the French expedition to Peru (‘Mr Short writes that an unlucky accident has happened to the French mathematicians in Peru. It seems they were shewing some French gallantry to the natives’ wives, who have murdered their servants, destroyed their instruments and burn’t their papers’), and Short's observation of the satellite of Venus before summarising ‘all that I have printed in my book relating to the attraction of spheroids and the figure of the Earth’, 3 pages

Footnote

A major collection of letters illuminating the working relationship of two leading lights of the Newtonian revolution, and two of the most important Scottish mathematicians of any era.

Colin Maclaurin was James Stirling’s junior by six years, but as a child prodigy beginning his studies at the university of Glasgow at the age of 11, quickly caught up with his older compatriot, so that their careers proceeded with a remarkable degree of conjunction. In 1717 Maclaurin was appointed chair of mathematics at Marischal College in Aberdeen, the year in which Stirling travelled to Italy, probably with his own hopes of a professorship. Their respective first books, Stirling’s Lineae tertii ordinis Neutonianae, published in 1717 with Newton listed as a subscriber, and Maclaurin’s Geometrica organica, published in 1720 with Newton’s imprimatur, were both responses to Newton’s ‘Enumeratio linearum tertii ordinis’. Maclaurin often complained of the burden of his teaching duties, first in Aberdeen and then as professor of mathematics at Edinburgh from 1725, and Stirling too was forced to balance his mathematical researches with his work as a tutor at Watts’s Academy in London and then as mines manager at Leadhills. It is probable that the pair became personally acquainted through the Royal Society, to which they were elected in 1719 (Maclaurin) and 1726 (Stirling). Although on opposing sides, both men were in their own ways victims of the Jacobite cause: Stirling’s departure from Oxford was directly the result of his Jacobite sympathies, while Maclaurin’s death closely followed his flight from Edinburgh in 1745 in anticipation of the arrival of Charles Stuart’s highland army. Stirling was offered the professorship at Edinburgh in succession to Maclaurin, but declined owing to his commitments at Leadhills. They are today buried in the same churchyard, Greyfriars, in Edinburgh, and are remembered, together with Maclaurin’s teacher Robert Simson, as part of the triumvirate of Scottish mathematicians active in the early 18th century ‘who all produced mathematical work that is still relevant today’ (Tweddle, ‘The Prickly Genius - Colin Maclaurin (1698-1746)’, Mathematical Gazette, 1998, Vol. 82 No. 495, p. 378).

These letters and that in the following lot are the entirety of the known letters from Maclaurin to Stirling as identified in the early 20th century by Charles Tweedie. A substantial primary source for the progression of Maclaurin’s priority dispute with George Campbell over the discovery of impossible roots, they also trace the development of key ideas in A Treatise of Fluxions (1742), with Maclaurin demonstrating ‘great reliance on Stirling’s judgment’ (Tweedie, p. 15), and provide a snapshot of the unfolding debate over the figure of the earth, to which both men made contributions of lasting importance. Perhaps more than any other letters in the library of James Stirling, they provide an insight into the material and social context of the exchange and development of ideas in the Age of Enlightenment, when the discovery of scientific and mathematical truths was dependent on contingencies including personal rivalries and friendships, the physical availability of books and articles, and social initiatives such as the foundation of learned societies.

Published:

Charles Tweedie, James Stirling: a Sketch of his Life and Works along with his Scientific Correspondence, 1922, pp. 57-9, 67-8, 69, 71-2, 73-5, 75-9, 79-80, 80-82, 85-8, 90-92.