Lot 102

Stirling, James (1692-1770)

Collection of autograph letters signed to members of his family, 1715-1762

The Library of James Stirling, Mathematician

Auction: 23 October 2025 from 13:00 BST

Description

19 in total, 27 pp., written from Oxford, London, Edinburgh and Leadhills, mainly addressed to his brother John Stirling, other recipients being his father Archibald Stirling (1651-1715), and brother Charles Stirling (d. 1739, merchant in Jamaica), including:

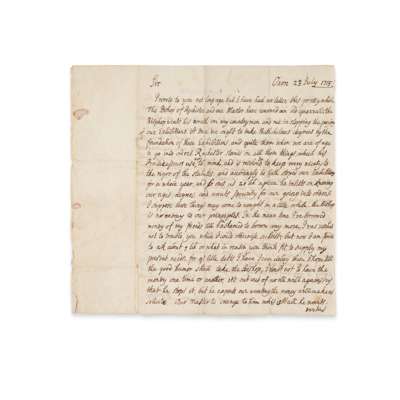

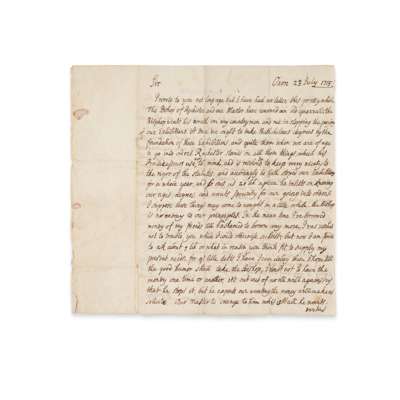

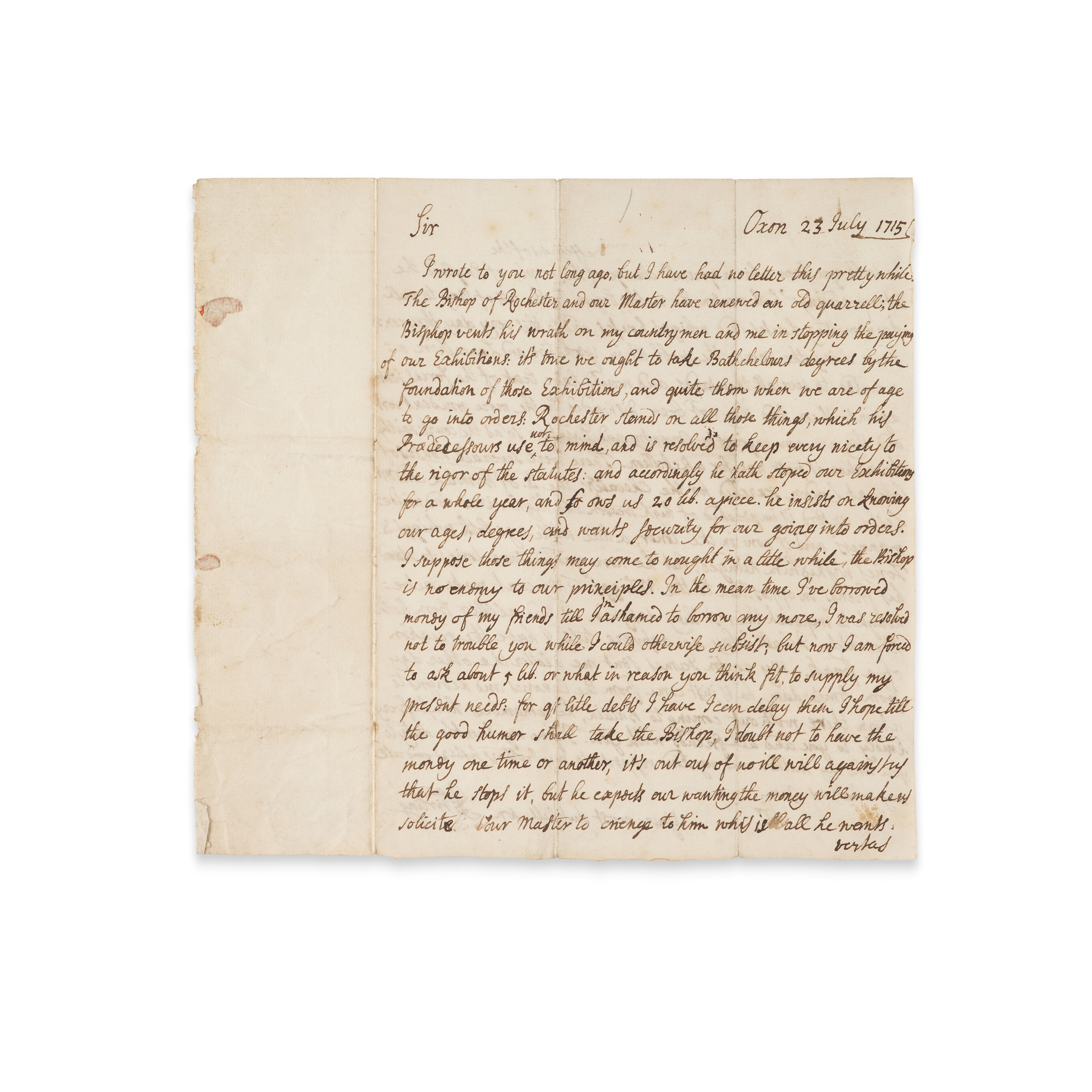

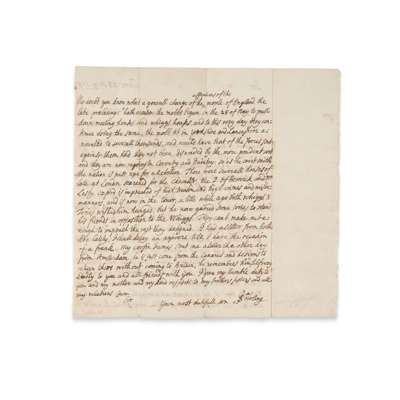

To Archibald Stirling, from Oxford, 23rd July 1715, describing Jacobite rioting across England and the withdrawal of his university scholarship (as a result of his being a non-juring student): ‘the Bishop [of Rochester] vents his wrath on my countrymen and me in the stopping of the paying of our Exhibitions … Now I am forced to ask about 5 lib … No doubt you know what a generell change of the affections of the people of England the late procedings hath occasioned; the mobbs begun on the 28th of May to pull down meeting houses and Whiggs houses, and to this very day they continue doing the same, the mobb in Yorkshire and Lancashire amounted to severall thousands, and would have beat of the forces sent against them had they not been dissuaded by the more prudent sort and they are now raging in Coventry and Daintry: so as the court saith the nation is just ripe for Rebellion. There were several houses of late at London searched for the Chevalier’, 2 pp.;

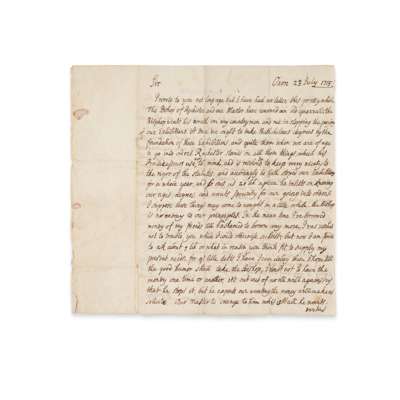

To John Stirling, from London, 5th June 1725, mentioning Isaac Newton apparently in connection to the search for a patron ('Sr Isaac Newton lives a little way of in the country, I go frequently to see him, and finds him extremly kind and serviceable in every thing I desire, but he is much failed and not able to do as he has done'), learning French ('I have changed my lodgings and am now in a French house and I frequent French coffee houses in order to attain the language which is absolutely necessary'), etc., 2 pp., loss of text from rodent damage;

and similar, on matters including: personal finances and domestic affairs ('I had 100 lib to pay down here when I came first to the academy and now have 70 lib more, all this for instruments'); society and family gossip including marriages and courtships; opportunities for family members in Guinea, Jamaica and the East India Company; family illnesses and deaths; improvements at Leadhills, and more

Footnote

An important collection of letters situating James Stirling the mathematician in his 18th-century milieu of Jacobite agitation, nascent commercialism, imperial expansion, and burdensome patronage networks, with the challenges of everyday life, notably personal finances and importunate relations, met variously with exasperation or recourse to bawdy humour. The collection was consulted by Charles Tweedie for his biography James Stirling: a Sketch of his Life and Work (Oxford, 1922), and by William Fraser for his family monograph The Stirlings of Keir and their Family Papers (Edinburgh, 1858, pp. 83-86), which provides useful background information on the other members of Stirling's family.

Stirling's father Archibald was a prominent Jacobite who had been tried for high treason for his role in the Brig o'Turk Gathering of 1708. Two years later James Stirling matriculated at Oxford as a non-juring student, having avoided taking the oath of supremacy. All the evidence of his ensuing university career indicates that he shared his father's sympathies, and, according to Tweedie ‘took a leading part among the Balliol students in the disturbances of 1714-16’. He is mentioned frequently by the non-juring diarist Thomas Hearne, who records that ‘Mr Stirling a Scotchman of Balliol College’ was arrested in December 1715, then tried and cleared at Oxford assizes a few months later for cursing George I. In 1717 Stirling left Oxford without a degree, apparently having refused to submit to the oaths and therefore regain his scholarships, instead taking up an invitation to Venice from the Venetian ambassador to London, a turn of events which introduced him to many of the leading scholars of Europe and therefore proved a decisive moment in his mathematical career.