Lot 179

Leicester, Robert Dudley, Earl of (1532/3-1588)

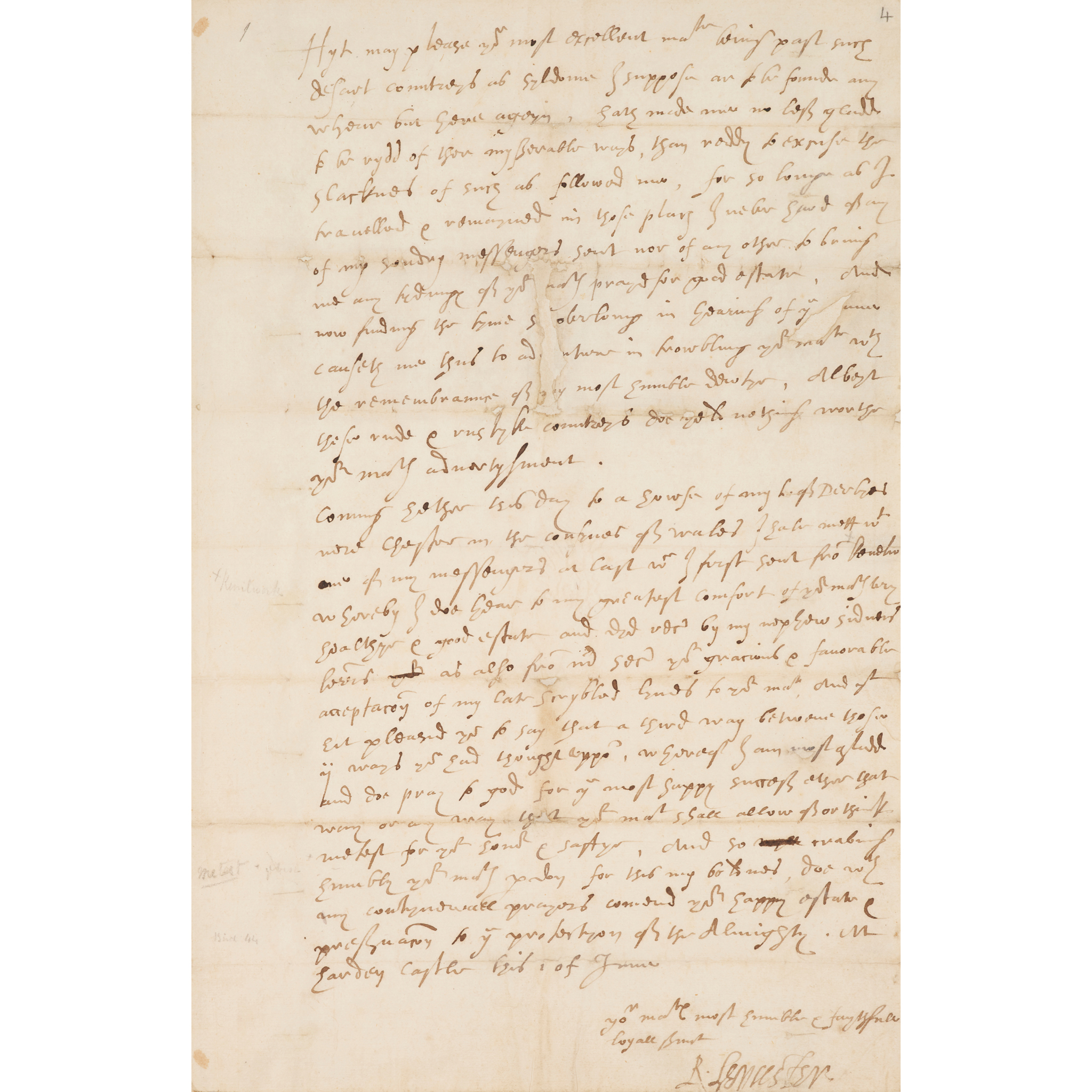

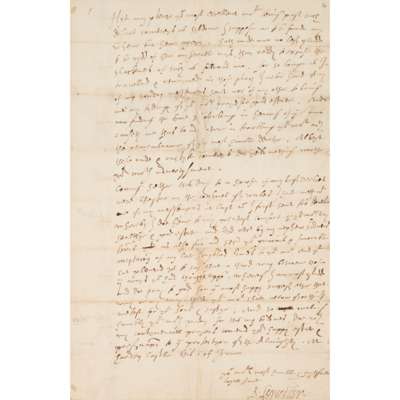

Autograph letter signed to Elizabeth I

Auction: 05 February 2025 from 10:00 GMT

Description

Harden [Hawarden] Castle, 1st June [1584]. Single bifolium (30.6 x 20.2cm), laid paper with phoenix watermark, written on one side only, signed at foot ‘R. Leycester’, conjugate blank endorsed in Leicester's hand ‘To your most excellent maj’ with ‘Lecester’ added below, possibly in the hand of Elizabeth I

Provenance

1. With W. W. B. Hulton, Esq. of Hulton Park, Lancashire, by 1891, probably having entered the possession of the Hulton family via the marriage of William Hulton (d.1694) to Anne, only daughter of William Jessop, clerk to the Council of State 1654-60 and legal agent for the executors of the third earl of Essex (d.1646), Parliamentarian general and step-grandson of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester; the return of this letter to the Leicester/Essex family, along with one other from Leicester to Elizabeth, and a substantial collection of letters to Elizabeth from the second earl of Essex, may have brought about through Leicester’s widow, Lettice, Countess of Leicester (1543-1634) (see Historical Manuscripts Commission, The Manuscripts of the Duke of Beaufort, K.G., the Earl of Donoughmore, and Others, 1891, pp. 165-6).

2. Thence by descent.

3. Sotheby’s, Elizabeth and Essex: the Hulton Papers, 14 December 1992, lot 2.

Footnote

An extremely rare example of an autograph letter to Elizabeth I from her lifelong favourite, evoking the troubles which beset this most complicated of relationships, and containing an enigmatic reference to an unspecified great matter of state, said to bear directly on the queen’s life and likely relating to England’s policy towards Scotland in the aftermath of the Throckmorton plot of 1583, the conspiracy between English Catholics and continental powers to overthrow Elizabeth and replace her with Mary Queen of Scots.

Leicester apologises with florid self-abasement for his elusiveness during his recent journey through the midland counties of England to ‘a howse of my L[ord] of Derbyes nere Chester in the confynes of Wales’, blaming negligent messengers and professing to be little impressed by the ‘rude and rustyke countreys’ he has passed through. Despite such protests Leicester was much in the habit of summer progresses, that of 1584 being the longest. He often took the waters at Buxton and Bath for sake of his health, which had been variable since a riding accident some 20 years before; another reason for such absences was doubtless the strain placed on his relationship with Elizabeth by his 1578 marriage to Lettice, dowager countess of Essex, whom Elizabeth loathed. Leicester was ‘forced to keep his marriage half hidden’ as a result (ODNB), and his 1584 journey was said by the French ambassador Mauvissière to have moved the queen to a fit of jealousy.

Referring to letters recently received from Francis Walsingham (‘Mr Sec.’) and his nephew Sir Philip Sidney, Leicester declares himself relieved to learn ‘that hit pleased you to say that [there is] a third way betwene those 2 ways you had thought uppon, whereof I am most glad and doe pray to god for the most happy success ether that way or any way that your majeste shall allow of or think metest for your honour and saftye’. In early summer 1584 the main threat occupying Walsingham as principal secretary was the instability in Scotland, where James VI, coming to the end of his minority, had on 10 May asserted his control by executing the Earl of Gowrie, leader of the Presbyterian Ruthven faction and enemy of the rival magnate the Earl of Arran. Three courses of action are known to have been entertained by Walsingham at this point: inciting a rebellion against James under Lord Alexander Erskine, commander of Edinburgh castle; using Arran as an intermediary to restore amity between Elizabeth and James (the so-called ‘by-course’); or using the imprisoned Mary Stuart to influence James in a direction favourable to England. (Walsingham personally favoured military intervention, but viewed the third option as the most practicable.) Meanwhile Francis Throckmorton was tried on 20 May 1584 and executed on 10 July. The attentions of Elizabeth’s were soon diverted, however, by twin crises on the continent: the death of her suitor the Duke of Anjou on 10 June, and the assassination of the Prince of Orange a month later. The next year Leicester travelled to the United Provinces as leader of the English expeditionary force sent to assist their revolt against Habsburg rule, being offered a few months after his arrival the position of governor-general of the Netherlands by the States General, which marked the climax of his political career. On his death in 1588 Elizabeth was distraught.

We have traced two other autograph letters from Leicester to Elizabeth. One, now at the Folger Shakespeare Library (X.c.126) and written from Tilbury while awaiting the Armada, was lot 1 in the Sotheby’s Hulton Papers sale of 1992 (see above) and contains the endorsement ‘Lecester, Tilberie' in the same hand as the present letter; the other, now at the National Archives, was written by Leicester a few days before his death and is famously endorsed by Elizabeth ‘his last lettar’.

Futher reading: Conyers Read, Mr Secretary Walsingham and the Policy of Queen Elizabeth, Oxford, 1925, volume 2, pp. 226-231.