Lot 193

Edward VI (1537-1553), King of England and Ireland

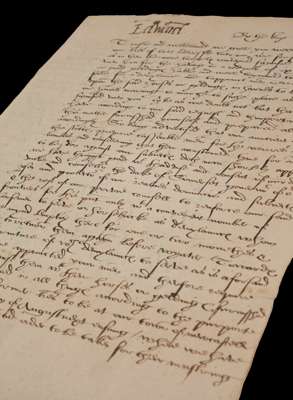

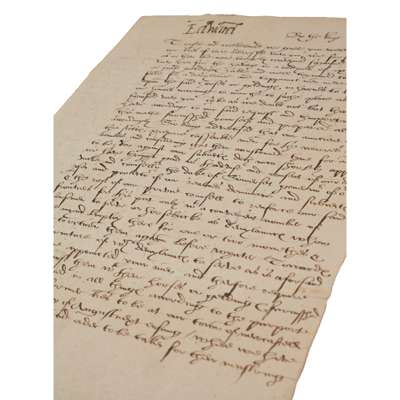

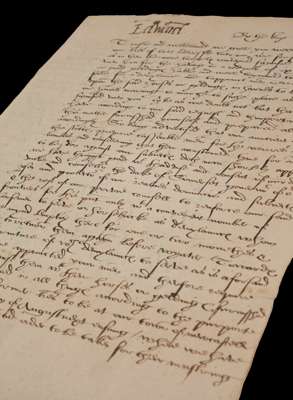

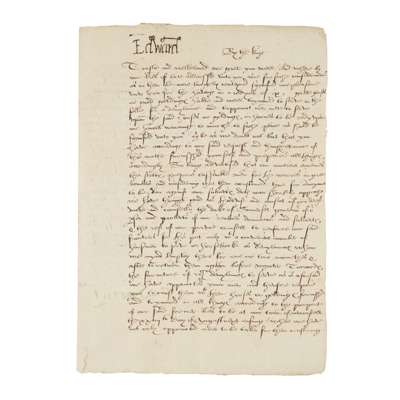

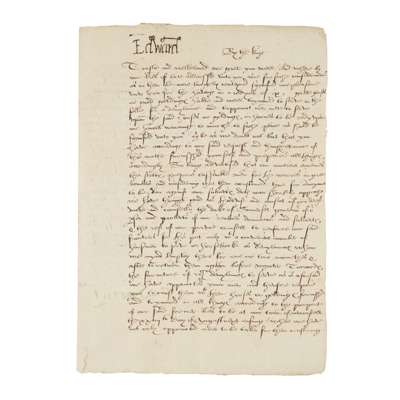

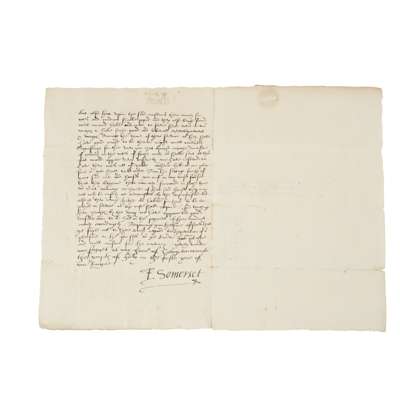

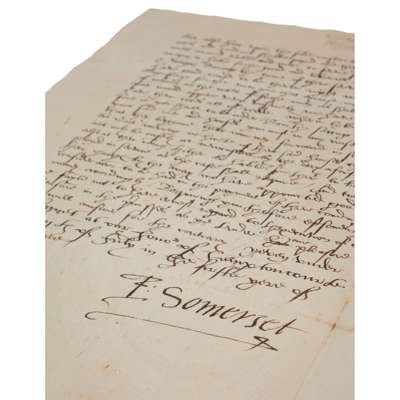

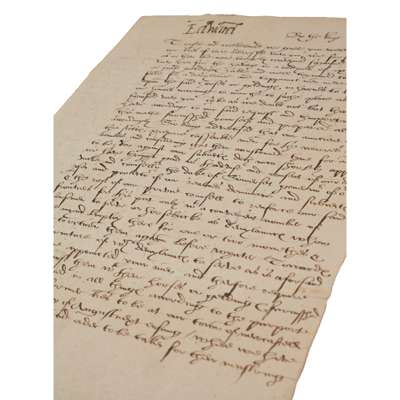

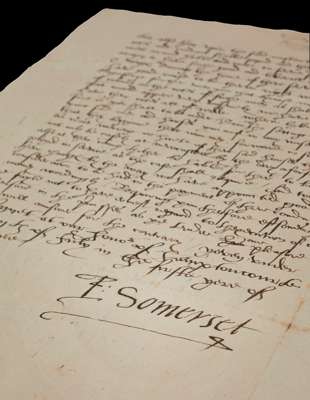

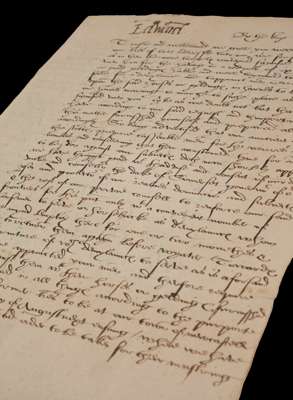

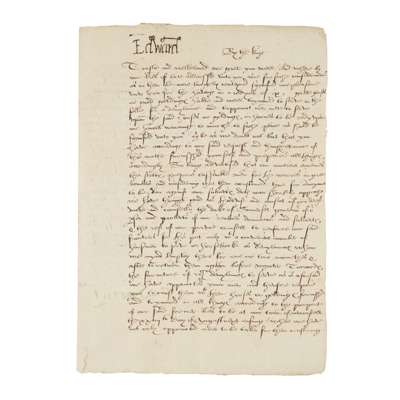

Letter signed with woodcut sign-manual, 14 July 1547

Auction: 19 September 2024 from 10:00 BST

Description

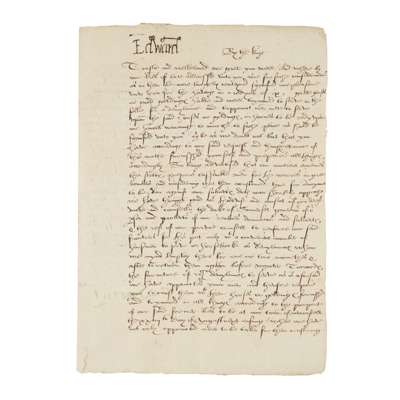

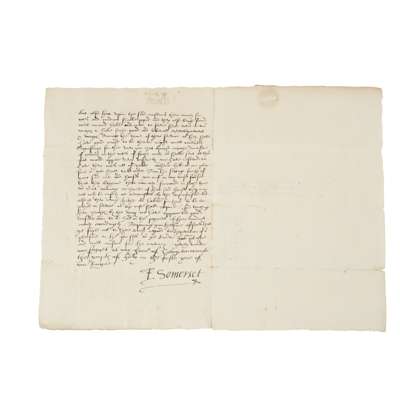

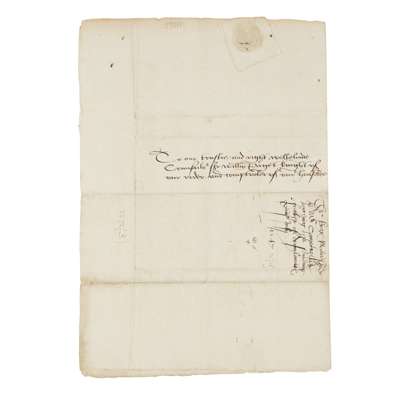

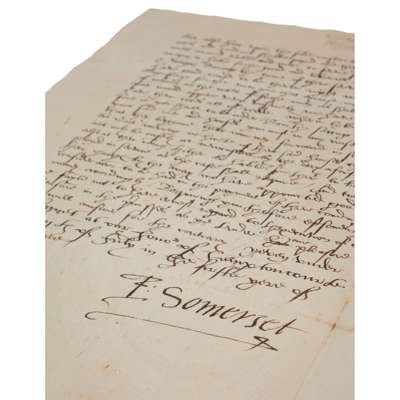

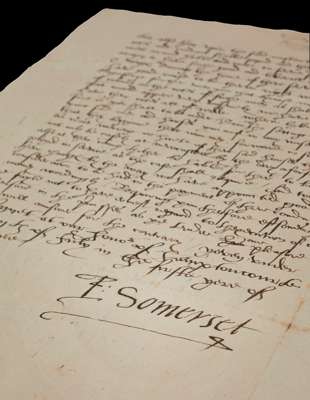

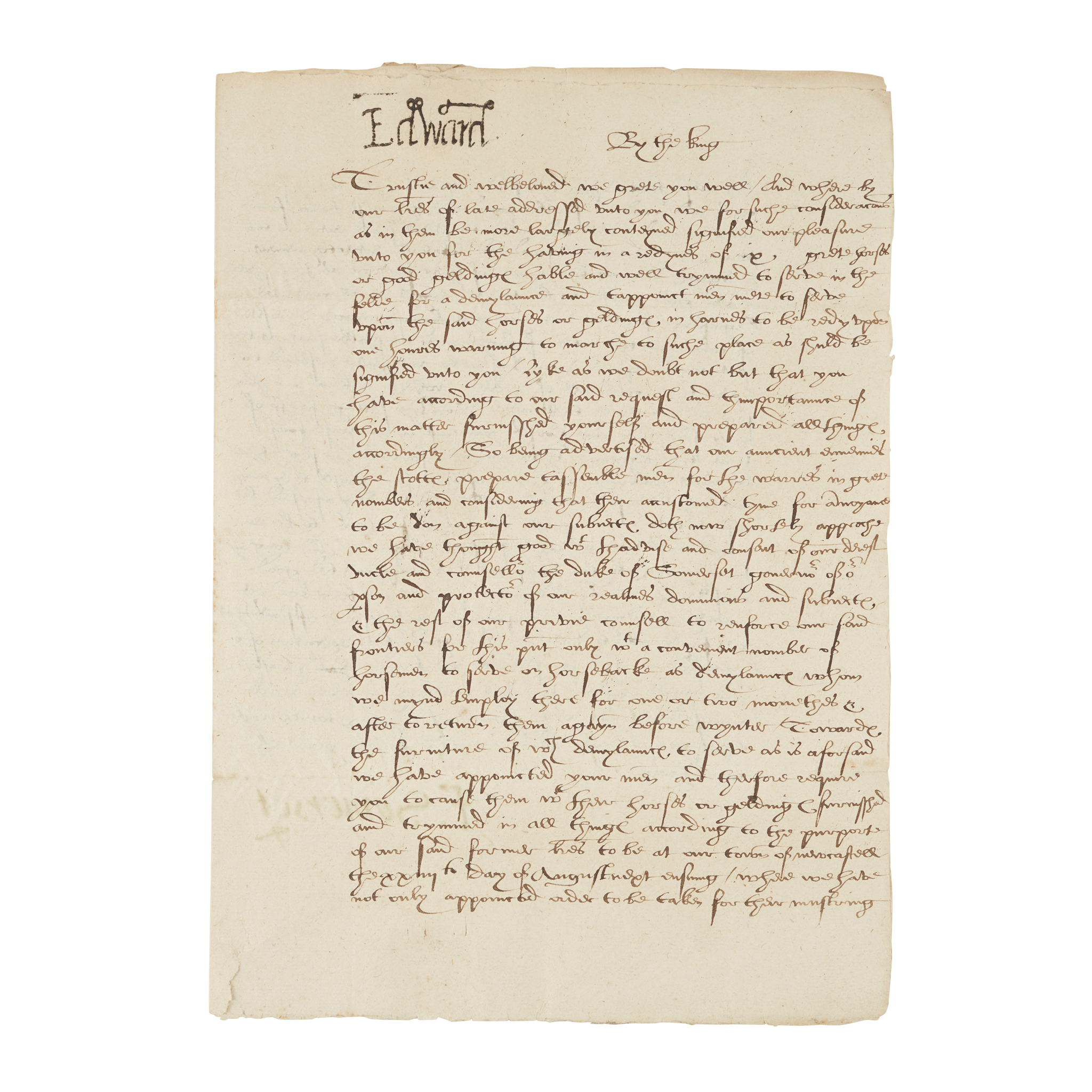

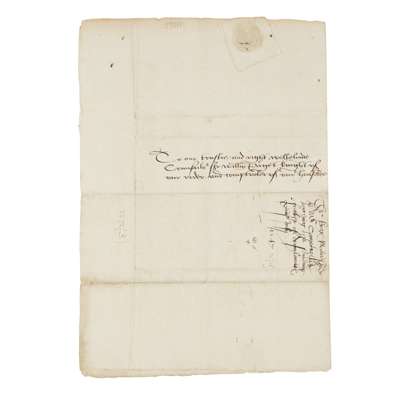

single bifolium (29.5 x 20.8cm, hand and flower watermark), written on two sides in a secretary hand, Edward's woodcut sign-manual to head, autograph countersignature of Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset as Lord Protector ('E. Somerset') to foot, addressed ‘To our trustie and right wellbeloved counsellor Sir William Paget knight of our order and comptroller of our household’ on verso of conjugate blank, wafer seal and contemporary endorsement to the same, short split to head of central fold, short tear to lower inner corner of first leaf, neither affecting text, a few other small holes

Footnote

Writing in the name of the boy-king Edward VI a few months after his coronation, Lord Protector Somerset instructs his main ally and fellow Tudor magnate William Paget to raise a unit of heavy cavalry in preparation for the renewal of England's campaign against Scotland, launched by Henry VIII in 1544 in order to secure the marriage of the future Edward VI and Mary Queen of Scots, and known to posterity as the ‘Rough Wooing’.

As the Earl of Hertford, Somerset had previously commanded the English forces which sacked Edinburgh in 1544, and achieved a superb victory against the French at Boulogne a year later. William Paget, as principal secretary to Henry VIII from 1543, was himself closely involved in his master's wars with Scotland and France, and in consequence formed a fateful double act with the soon-to-be Lord Protector: ‘The [English] military commanders had come to depend on him for communication with the King while they were campaigning, and among them the Earl of Hertford, soon to be raised to the dukedom of Somerset, developed a relationship with Paget which was to be of great importance after the change of sovereign, when Paget became the Protector Somerset’s constant companion … It was the new King, or the Protector Somerset in his name, who gave Paget the Garter, and upon his resignation as secretary made him comptroller of the Household and chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster. While Somerset was with the army in Scotland during the summer of 1547 Paget was the effective head of the government’ (Bindoff, ed., The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1509-1558).

England and Scotland had been at peace since the Treaty of Camp in June 1546, but as the present letter demonstrates, this was a period which Somerset used to prepare for war. Professing himself ‘advertysed that our auncient enemies the Scottes prepares tassemble men for the warre in grete nombers’, he requests that Paget send him ‘x [ten] grete horses or good geldings hable and well trimmed to served in a felde' and ‘a convenient nomber of horsemen to serve on horsebacke as demylaunces', to muster at Newcastle by late August.

The 14th of July 1547 appears to have been an especially important date in these preparations. On the same day Somerset wrote to Archbishop Thomas Cranmer requesting dispatch of 15 horsemen, and it is presumed that similar demands were sent to other magnates. It is also the first recorded date on which Somerset appears to have assumed sole responsibility for witnessing the king's directives for raising troops, without the countersignature of any other privy councillor, a further expansion of his already near-complete control over the affairs of the realm, in which his access to the king's woodcut sign-manual or ‘dry stamp’, held by his ally in the royal household, vice-chamberlain Sir John Gates, was a key component.

Paget's horsemen were doubtless to be involved in the battle of Pinkie on 10 September: the final pitched battle between the independent kingdoms of England and Scotland, it resulted in a swift and crushing English victory; but Somerset's military success was also the start of his downfall, ruining the nation's finances while encouraging him to abandon government in council for personal rule conducted more or less entirely from his own household. Paget was disturbed by Somerset's autocratic turn but remained by his side until the Earl of Warwick's coup in 1549, when he advised Somerset to surrender to his great rival, and in fact arrested him on the latter's behalf. Somerset was eventually executed in 1551; Paget's fortunes endured violent fluctuations with successive changes of regime, but he remained a magnate and died an old man in 1563, his heirs becoming the marquesses of Anglesey.